Cage Match

John Cage: Vanguard of the Avant-Garde

John Cage (1912-1992), the leading American avant-garde composer of his generation, experimented tirelessly throughout his career. In the years leading up to 1951, Cage began to embrace the concept of indeterminacy, which would ultimately come to define his work. The idea of music created “by chance” became a source of ongoing confusion about Cage’s works and ultimately cost him the support of some of the influential musicians who had championed his earlier efforts. Paradoxically, this indeterminacy also proved to be Cage’s most influential and enduring compositional idea for posterity.

Cage first studied theology and then dabbled in architecture, painting and poetry. From 1933, Cage committed himself to composition, working for a time with the composer Henry Cowell (1897-1965). In 1935, Cage joined the class of Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) at the University of Southern California and at the University of California Los Angeles. Cage worshipped Schoenberg but by 1937 had come to find the Austrian master’s strict adherence to formal harmony stifling. Cage left Schoenberg’s class to pursue composition on his own. Schoenberg, who was known to be dismissive of the ability of virtually all of his American students, said of Cage, “…of course he’s not a composer, but he’s an inventor—of genius.”

Indeed, Cage would go on to “invent.” He began to experiment with music created from random sources like household items, glass bottles, metal sheets, and duck calls. Cage invented the concept of “prepared piano,” altering the sound of the instrument with tape, glass rods, and other objects on or below the strings. Prepared piano was to become a staple in the growing arsenal of new compositional techniques through the end of the 20th century and beyond. Similarly, Cage’s repurposing of ordinary objects as musical instruments would become a continuing source of inspiration for invention in music for composers such as George Crumb (b. 1929), who applied the use of “found instruments” with great effect in pieces like Black Angels (1970) and Vox Balaenae (1971).

In his post-Schoenberg period, Cage became closely linked with the composer Lou Harrison (1917-2003) in Oakland, California. Harrison and Cage developed mutual interests in Eastern musical forms as well as percussion and dance. During this time Cage also began to develop what would be a lifelong interest in Indian and Buddhist philosophies. Cage eventually left Oakland for the Cornish School in Seattle, Washington where he began to gain renown touring with a percussion ensemble he created. In Seattle, Cage began actively collaborating with dancers and choreographers including Merce Cunningham, with whom he would have a lifelong romantic and collaborative relationship.

One Last Step

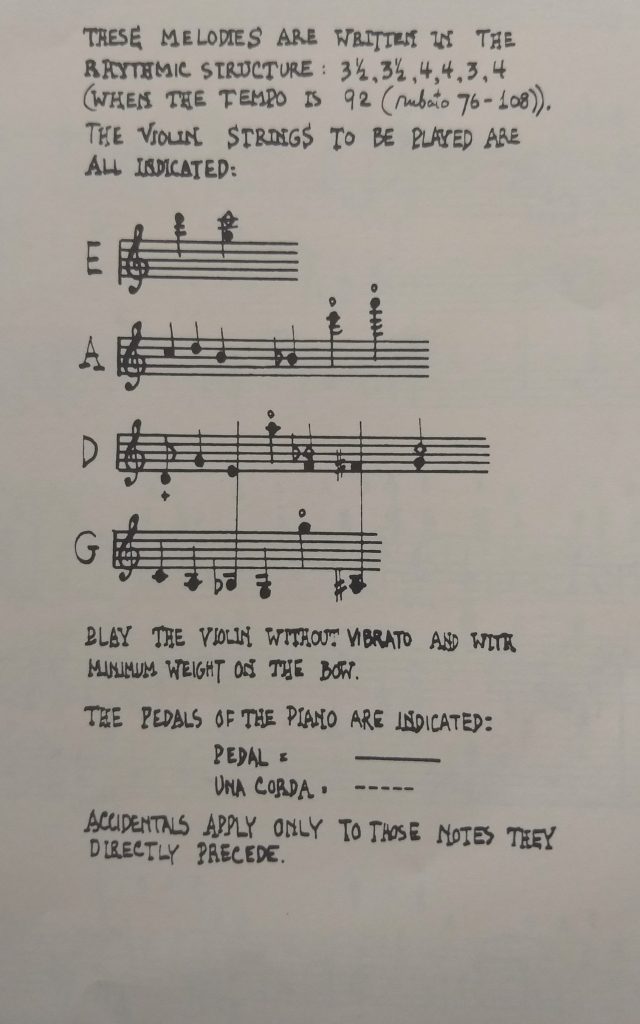

Cage’s Six Melodies from 1950, (to be featured on This Week from Guarneri Hall with violinist Ben Baker and pianist Daniel Lebhardt on November 29, 2020) marks a last evolutionary step in the composer’s progression to the full-blown indeterminacy that would inform the rest of his compositional output. The Six Melodies are constructed of chance operations using two devices, “gamuts” and “nested rhythmic proportions.” Gamuts are a series of fixed sonorities that are prepared in advance. The “nested rhythmic proportions” define the relative lengths of each rhythmic unit in relation to one another. Everything else about each performance is randomized such that no two readings will be alike. What is remarkable is how organized the pieces sound nonetheless. Ultimately, Cage’s search for an effect even more untethered from the will of the composer and performers would find him further reducing fixed compositional formalities. But Six Melodies and its close preceding cousin, the String Quartet in Four Parts, represent an important inflection point in Cage’s development, foreshadowing a shift in compositional technique from which Cage would never return.

A “Chance” Encounter

In 1951, Cage’s student, the composer Christian Wolff (b.1934), presented Cage with a copy of the newly published English translation of the I Ching. This classic Chinese work lays out a system of symbols by which to order events by chance to divine a higher truth. Using the I Ching, six random numbers from 6 to 9 are arranged into a hexagram. Each hexagram can be found in the text and applied to the question at hand. The randomizations of the I Ching are designed as a means of reaching answers free of human influence, appealing to a presumed spiritual intervention. The I Ching and its underlying concept would come to exert a profound influence on Cage. Cage began to use the I Ching to create a series of “chance operations” that could be strung together into a piece of music. Cage conceived of the indeterminacy of this process as “imitating nature in its manner of operation,” a way to free the process and the music of the ego and will of the composer.

Cage went to the next logical step with his very next composition, Imaginary Landscape #4, a work constructed entirely of chance operations as determined using the I Ching. Cage scored Imaginary Landscape #4 for 12 radios and conductor and prefaced the score with a long list of instructions for the performers. The piece exemplifies Cage’s relentless search for a way to disengage control as a composer so as to remove the creator’s will and ego from the work. As Cage put it, “It is thus possible to make a musical composition the continuity of which is free of individual taste and memory and also of the literature and ‘traditions’ of the art. The sounds enter the time-space…centered within themselves, unimpeded by service to abstraction.”

Irreconcilable Differences

The notion of chance and indeterminacy in composition marked a radical break from the strict compositional control that was explicit in the methods of Schoenberg and those who followed him. Prior to 1950, Cage’s music had been built on the basis of traditional formality reinforced by Shoenberg’s teaching. The new ordering of chance operations marked a profoundly different path than the hyper-controlled sounds and precision being pursued by the post-Webern avant-garde including Cage’s friend and supporter, Pierre Boulez (1925-1916). Cage’s leap ultimately proved to be a bridge too far for Boulez. A rich and warm correspondence between the two, begun in 1949, broke off in 1954. Subsequently, Boulez was known to give Cage faint praise at best. Ultimately, a group of composers who had held Cage in high esteem prior to 1950, including Boulez and composers Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007) and Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001), dismissed the indeterminacy of Cage’s mature works and the press turned their back on Cage for many years.

Four Minutes and 33 Seconds that Changed the World

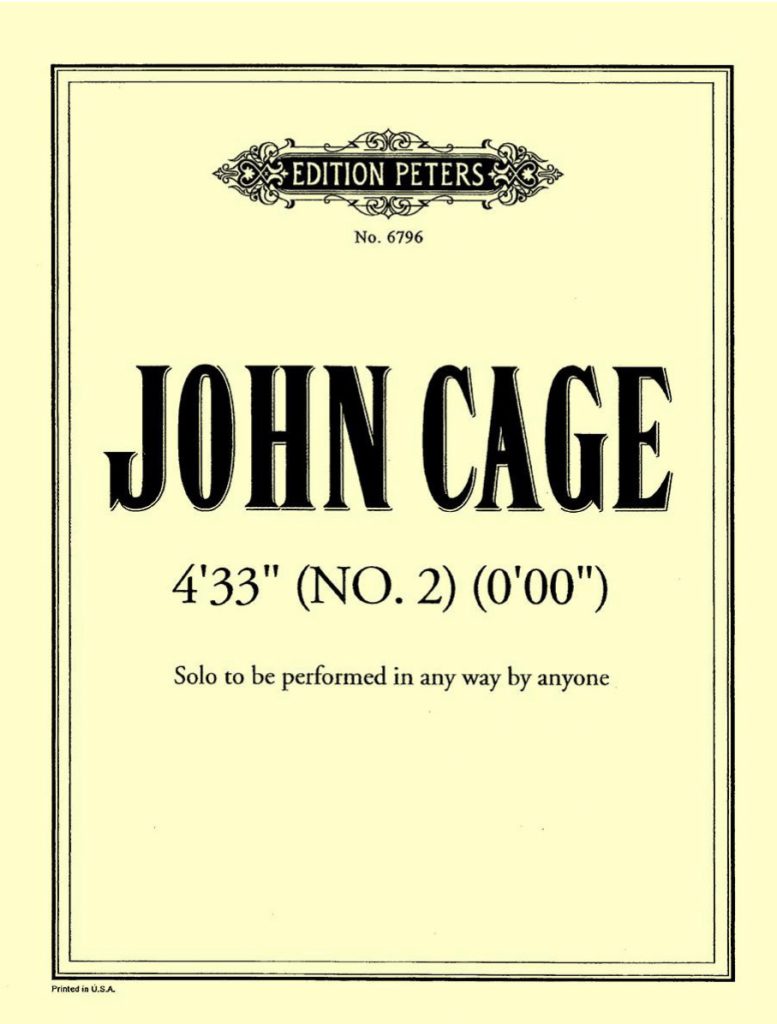

The purest form of Cage’s indeterminacy can be found in his most famous (and infamous) work, 4’33”, from 1952. 4’33” calls for a solo pianist to sit at the instrument without playing for the proscribed time. Four and a half minutes is, for both performer and audience, an achingly long time for a musician to remain on stage alone playing nothing. Such a work is easily misunderstood: is 4’33” a joke? Is Cage advocating for silence? Is he scoffing at the new music world? As it happens, none of the above. Among other things, 4’33” demonstrates that silence isn’t actually possible in a concert setting. Much as with a Zen meditation, the imposed stillness of 4’33” ultimately exposes the many environmental sounds that humans tune out in day-to-day life. The piece is long enough that audiences have time to recover from the initial discomfort of the imposed stillness and begin to recalibrate both the scale of the perceived sound world and of the sense of the passage of time.

Cage would continue to “divine” compositions using the I Ching for the rest of his prolific career. Cage himself regarded 4’33” as his most important composition, one which he said he referenced in all subsequent compositions. The piece, along with so many of Cage’s ideas, have had a deep and lasting influence on music since.