Talking the Walk: A Profile of Composer Augusta Read Thomas

If talking about music, as the old saying goes, is as futile as dancing about architecture, how do you find words for the elusive process of composing? If you’re Augusta Read Thomas, you scat.

-Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim

Talking the Walk

In an interview, the Pulitzer-finalist composer and University of Chicago professor spoke eloquently about her craft and the myriad decisions that go into creating the vibrant, deeply hued works that have made her one of the most frequently performed living composers in America. Along the way, her speech sometimes morphed seamlessly into song, as she illustrated a thought with melodic volleys of crisp nonsense syllables.

Music Has Its Own Truth

“Let’s say you’re writing a line, maybe for flute,” she began, warming to the subject of rules in music. Ba-DEE ya-papa-paPAA pa-pee-paka-kum-chAAaa, she sang, with a tiny swell on Ba-DEE, the last syllable tapering off to an expectant hush. “It already has a million rules,” she said. “It’s capricious, it has unexpected turns, it has loud notes and soft notes, and there’s an implied harmonic rhythm. If you follow that with boom-chick-chick-boom-chick, that would be stupid. But if the next phrase did something like jaDEEE-badee-dadee-BAWdeee, I’ve still got my listener.” The final tune rang out sweetly assertive, a reassuring response to the first.

Thomas said she never followed a system of composition such as Serialism because “the material tells you what it has to do next.” If you learn to hear it, she maintains, “music has its own truth.”

Ritualistic Sounds

Thomas began scatting early. Her main instrument as a child was the trumpet, her musical idols Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald. She said nobody who knew her was surprised when in 2019 he unveiled an opera featuring a virtuosic beatboxer. But what she is best known for is her unerring ear for complex rhythms and shimmering sound colors that are often a blend of disparate instruments. Tutti chords melt away into the sustained resonance of a gong or a tiny crotale, creating a sense of surprise and wonder. At moments like these, it feels as if the heavy curtain of symphonic sound was pulled back to reveal the sound of something ritualistic and ancient.

Thomas says integrity is one of the pillars of music. Not only does the material have to belong authentically to the composer – “it needs to be bubbling in the stomach of its own-ness,” as she puts it – but its various components need to be integrated with thought and care. “When it’s well done,” she said, “you feel so confident as a listener.”

The Clarity of Language

Thomas puts just as much thought into the confidence of her performers, and it is here that her knack for connecting verbalizing music again makes itself felt. Part of the price of success for a composer is distance. “Most of the time, I never meet my players,” Thomas said. By her own account, in the week of our interview, some 2,000 musicians were practicing parts to her compositions – as soloists or as members of symphony orchestras in Houston, Chicago and Rochester. “I’m eternally grateful to them,” Thomas said, “but I’m never going to meet them. It’s out of generosity to these people, who are so generous to me, that I want my scores to be clear. I want to give them the confidence that they know what I want.”

To capture her musical ideas, she uses traditional notation as well as colorful graphic maps – and lots of words. “My scores are riddled with words,” she said. “I might put in majestic and two beats later interior. Ardent. Suddenly playful. One of the comments I get from performers worldwide is, ‘thank you for all those adjectives.’ Musicians find them so helpful.”

Write It In

Composer Augusta Read Thomas said she developed the habit as a student composer when she attended rehearsals of her pieces. “I would say, ‘Can you play that majestic?’ and they’d take a pencil and write it in. I was watching this and thought, well, why don’t I just write it down in the score?” She said she also began replacing the traditional rehearsal letters labeling the various sections in a score with expressive markings. “I like it when the conductor has to say, ‘Let’s take it from resonant’ or ‘Let’s take it from driving and playful.’ That way he – it is usually a he – is telling the orchestra exactly what I’m trying to say to them. And the musicians are actually teaching themselves how to color a phrase.”

But Thomas doesn’t content herself with mere adjectives. A high-energy spot in her third violin concerto contains this instruction to the soloist: Jump in the getaway car. “It might sound like the most ridiculous thing to write on a piece of music,” Thomas said, “but it gets you engaged, and it’s exactly what’s happening dramatically in the music.”

Mapping It Out

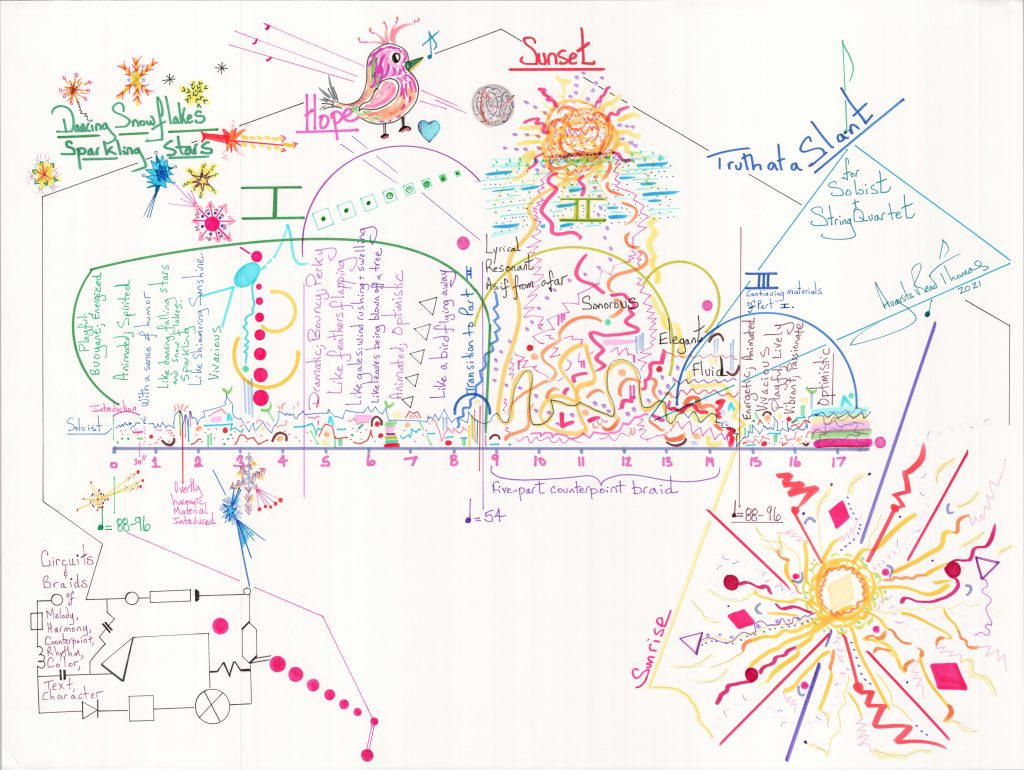

The compositions of Thomas also come accompanied by colorful hand-drawn maps. These are like graphic representations of the fluctuations in mood and energy of each piece, supplemented with figurative drawings of non-musical concepts and geometric symbols. But Thomas said that most of the maps that listeners encounter in the pages of a concert program are made after the fact, as a snapshot of the finished score.

As part of her composition process, she said, she will draw and discard as many as 100 maps along the way. “Part of it is about sculpting time,” she said. “I ask: what am I building? Is it an arc? Is there a crescendo? I’ll draw a map, and I’ll improvise at the piano, and then I’ll throw the map out because I’ll realize it’s not what the music wants. And I’ll draw another.” Although she said she never ends up following them, her maps give her a useful bird’s-eye view of the emerging music and how it spreads out in time.

Giving Back

Her gift for communicating the how and why of her music also makes Composer Augusta Read Thomas a natural teacher and mentor. At the University of Chicago, where she holds the prestigious title of University Professor, she founded the Chicago Center for Contemporary Composition – never programming her own music but turning the spotlight on fresh talent. “I fight for other people night and day,” she said. In 2016 she created the innovative Ear Taxi Festival, also in Chicago. The list of boards and non-profit organizations that she has devoted her time to is long and includes the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Koussevitzky Foundation, the American Music Center, Third Coast Percussion and the International Contemporary Ensemble. “Citizenship is very important,” she said. “The profession needs people that really give back with a lot of blood, sweat, and tears” – and, she might have added, well-chosen words.