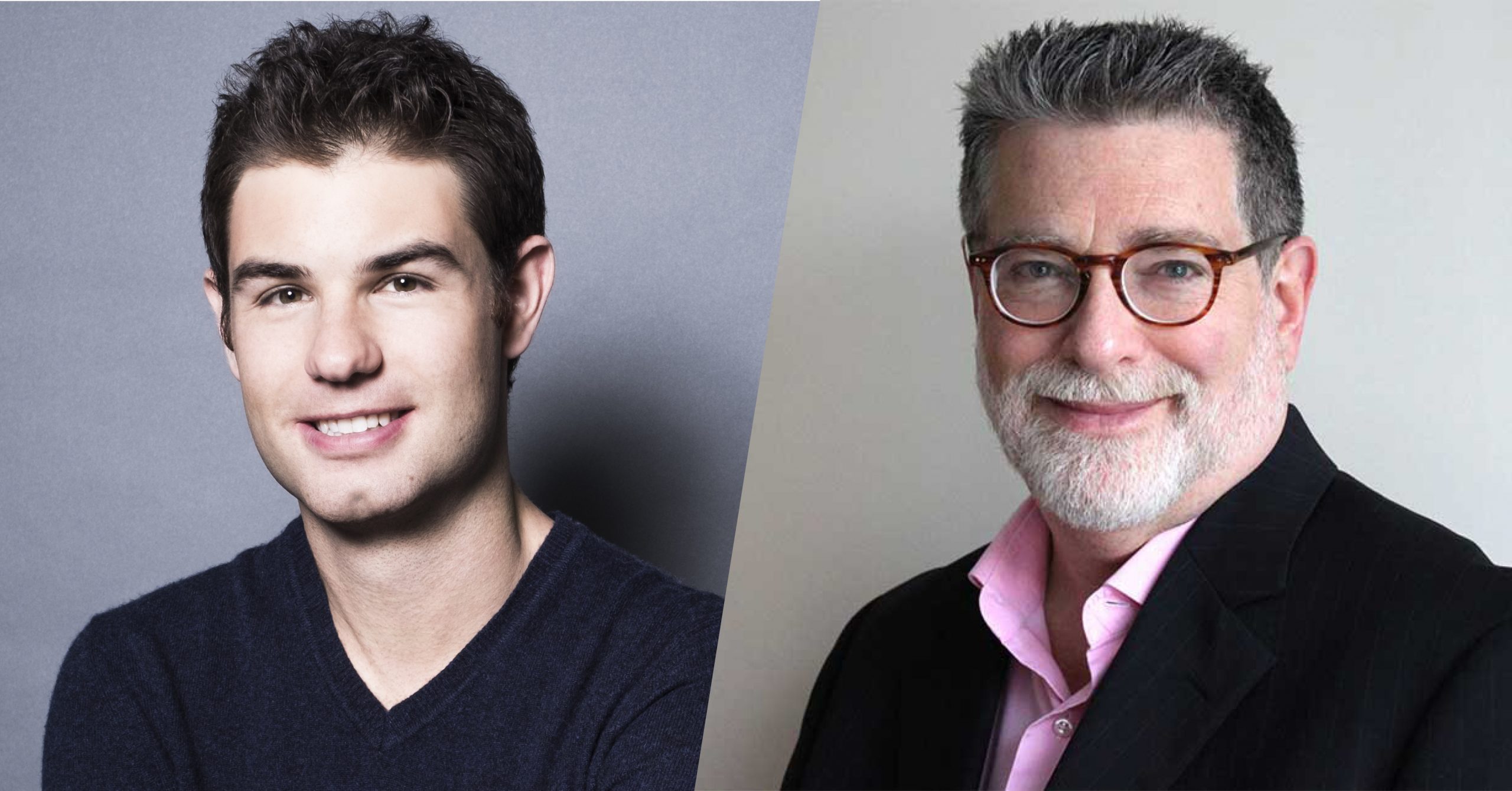

Program Notes: Violist Toby Appel and Pianist Drew Petersen

Thursday, January 9, 2020 @ 6:30 pm CST

Toby Appel, the incomparable violist and Juilliard faculty artist, joins the extraordinary young, prizewinning pianist Drew Petersen in recital in Guarneri Hall. The program includes works by Schumann, Shostakovich, Joachim, Clarke, and Friskin.

Full program details and ticketsJames Friskin: Elegy

James Friskin was born in Glasgow and studied in London at the Royal College of Music, where his composition teacher was Charles Villiers Stanford, one of the leading English musicians of the period. Although he began to compose early, his career as a composer effectively ended in 1914 when he accepted an invitation to emigrate to the United States to be a founding faculty member at the Institute of Musical Arts in New York, which eventually became The Juilliard School. He would remain a faculty member at The Juilliard School until his death while also pursuing a career as a pianist, specializing in the music of Bach. He is credited with having given the first performance in the United States of Bach’s Goldberg Variations in 1925.

The brief Elegy for viola and piano dates from 1912 and appears to have been written with the violist and composer Rebecca Clarke in mind. The two had met as students and worked briefly as musical colleagues. Eventually, some 30 years later in 1944, they would meet by chance in New York and would marry, each at age 58.

The Elegy beautifully exploits the expressive possibilities of the viola. As might be expected of an elegy, it begins in a somber minor key. A faster middle section changes to a brighter mood and the work eventually ends quietly in a major key.

Dmitri Shostakovich: Sonata for Viola and Piano, Op. 147

The Sonata for Viola and Piano was Shostakovich’s last work. It is perhaps not surprising that such an opus might not be exactly light-hearted, coming from a composer who knew he was mortally ill and could look back on a life lived through some of the most horrific events in modern human history, including such things as the siege of Leningrad and decades of Stalinist rule during which he lived in daily terror of the gulag or execution if his music failed to please the General Secretary and his minions. Shostakovich’s late style is certainly austere, often seeming to look backward in time, sometimes seeming to express despair, sometimes philosophical resignation, sometimes even a grim humor. All of these characteristics apply to the viola sonata.

As Shostakovich was working on the sonata in the summer of 1975, he contacted Fyodor Druzhinin, violist of the distinguished Beethoven String Quartet, the group that had premiered most of the composers 15 string quartets. At first the composer asked for advice on technical details but then revealed that he was dedicating the work to Druzhinin. Much moved by the dedication, Druzhinin obtained the parts and began to rehearse intensely with his pianist in hopes of performing it for Shostakovich. In the meantime Shostakovich died on August 9 without having heard the work. The first performance took place in the Shostakovich apartment for a gathering of friends some weeks later. The first public performance occurred in a memorial concert on October 1 in the Small Hall of the Leningrad Philharmonic. According to the composer’s biographer Laurel Fay, as the audience stood, “Druzhinin solemnly held the score over his head to an intense ovation.”

The sonata is in three movements, slow-fast-slow. Druzhinin said that Shostakovich called them respectively a novella, a scherzo, and a final adagio in memory of Beethoven. The opening movement begins mysteriously with solo viola pizzicato notes which are in fact, in C major as promised. When the piano enters a few bars later, however, it is with a theme that could hardly be more different; it is nothing less than a so-called tone row using all 12 notes of the chromatic scale and therefore not in any key at all but actually atonal music. The conflict between tonality and atonality contributes much to the darkly enigmatic quality of the movement. After a turbulent middle section the music returns to the quiet atmosphere of the opening.

The scherzo brings us music that is more familiar Shostakovich. The word scherzo means “joke” in Italian but here we have not light humor but his famous, typical, bitingly sarcastic, deeply ironic humor. Much of the music of this movement comes from his unfinished opera The Gamblers, begun decades earlier and then abandoned.

The finale, a tribute to Beethoven, is by far the longest movement of the sonata. Shostakovich himself described the movement as “radiant” and he clearly wanted it to attest to his lifelong respect for the German master. The listener will recognize snatches of music from Beethoven’s famous “Moonlight” Sonata, but the movement contains many other quotes as well, including one from Tchaikovsky, one from Rachmaninoff, and many of Shostakovich’s own works.

Finally, it is safe to say that this is unlike any C major sonata the listener has ever heard. Long stretches employ not just the white notes of the C major scale but many black notes as well, frequently giving us no key at all. Having said that however, after all the darkness and turmoil the sonata does actually end on a quiet C major chord which resolves all tension. It is hard to imagine a C major chord, that most basic harmonic structure of Western music, anywhere else in music that has more personal or philosophical significance than the last “radiant” chord that Dmitri Shostakovich ever wrote.

Joseph Joachim: Hebrew Melodies for viola and piano, Op. 9

Had Joseph Joachim never written a note of his own music he would still be remembered as an important figure in nineteenth century music. As one of the leading violinists of his time, he upheld the highest musical ideals in his playing, almost single-handedly establishing such works as the Beethoven Violin Concerto and the solo Sonatas and Partitas of Bach as important works in the violin repertoire. This was at a time when many violin soloists were more interested in virtuosity for its own sake than in genuine musical values, and refused to play such works. Joachim was closely acquainted with many of the most important composers of the time, including Mendelssohn, Liszt, Robert and Clara Schumann, and most famously, Brahms, who dedicated his monumental violin concerto to Joachim and worked closely with him, asking advice on many technical matters. Joachim even went so far as to write a cadenza for the work.

Joachim’s creative powers were certainly no match for his re-creative skills but he did leave behind a small body of well-crafted works, most of them written in the period between 1852 and 1865, when he was in his twenties and thirties, serving as concertmaster and conductor for King George of Hanover. Among the few works which have held a place in the repertoire are the beautifully expressive Hebrew Melodies for Viola and Piano, dating from 1855, which carry the subtitle “From Impressions of Byron’s Poems.” Being himself of Jewish ancestry, Joachim was naturally interested in the topic of Hebrew melody, although ironically, soon after writing the work he converted to Lutheranism, a common occurrence at the time among Jews living in the German states.

The Hebrew Poems of Lord Byron are an interesting part of literary as well as music history. This set of 30 poems, mostly written in 1814 and 1815, were requested by Isaac Nathan, the son of a cantor and a composer who set himself the task of collecting music from Jewish synagogue usage and adding words of high literary quality. Although he claimed that that the melodies were a thousand years old and had been sung by the ancient Hebrews, most of them were actually European folk songs which had over time worked their way into Jewish liturgical practice. Lord Byron obliged with a number of poems on Hebrew themes, including “We sate down and wept by the waters of Babel,” but also included several earlier love poems including what is probably his most famous poem, “She Walks in Beauty.” Nathan’s settings of these poems had wide circulation throughout the nineteenth century but many other composers set them as well, including Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, and Modest Mussorgsky.

The three movements of the Hebrew Melodies make no direct reference to specific poems but capture in a general way the spirit of lamentation that pervades many of the poems. The opening movement, marked Sostenuto, provides a feeling of deep pathos beautifully conveyed by the rich, dark voice of the viola. This movement is primarily in a dark minor key although it ends quietly in a major key. The second movement, marked Grave, is again in a minor key, this time with more restless and agitated rhythms. A more optimistic section moves to a major key in the middle and after reaching a climax then returns to a quiet minor key ending. The final movement, Andante cantabile, presents a change of mood with a graceful almost dance-like movement in a major key. A more dramatic middle section provides contrast before a return to the opening dance-like material that bring the work to a quiet close.

Robert Schumann: Märchenbilder, Op.113

Although Schumann was quite capable of writing large works, four fine symphonies for example, he often gives the impression that he was perhaps most comfortable in smaller forms. In addition to being one of the finest song writers of his era, he wrote instrumental music that often featured short movements which created a particular mood and were often programmatic, i.e., referring to ideas outside the music itself. Such pieces, usually for piano alone, or for piano with one solo instrument, were common during the Romantic period and became known by the German word Characterstück, or “character piece.” The Märchenbilder (Fairy Tale Pictures) for viola and piano are good examples of the genre.

The Märchenbilder are late Schumann, written in 1851 while he was music director in the town of Düsseldorf. Although this period of his life had its frustrations, including difficulties in his work as a conductor (he was by all accounts a poor conductor) as well as the worsening of the mental illness that would lead to a suicide attempt in 1854 and his eventual commitment to an asylum, he continued to compose at a brisk rate.

Schumann gives no hint as to what actual fairy tales he had in mind, allowing the listener to give free rein to the imagination as the music progresses through four separate movements, each with its own strikingly different mood. The opening movement, marked Nicht schnell (“not fast”), is a dreamily melancholy picture in D minor, featuring graceful interplay between the two instruments.

The second movement, marked Lebhaft (“lively”), creates quite a different impression, with proudly majestic dotted rhythms in a major key. This passage acts as a refrain, returning two more times after being interspersed with two contrasting playful, almost dancelike episodes.

The third movement, Rasch (“quickly”), is in clear ABA form, a structure commonly used in character pieces. Here, the first and last sections are in a fiery minor key, requiring virtuoso playing in both viola and piano. The contrasting middle section is quietly lyrical and set in a distant major key.

The final movement is marked Langsam, mit melancholischen Ausdruck (“Slowly, with melancholy expression”). If the dominant mood to this point has been one of restless, sometimes fiery drama, achieved through agitated rhythms and an emphasis on the dark key of D minor, the finale provides something completely different. Set primarily in the key of D major, this movement presents us with a gentle, childlike melody that could very well serve as a lullaby and brings this remarkable work to the gentlest of conclusions.

Rebecca Clarke: Morpheus

Rebecca Clarke was a pioneer both as violist and composer. After her training at the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal College of Music, she became one of the first female professional performers in London. In 1916 she traveled to the United States to pursue her performing career, where on a recital in New York, she performed several works marked on the program as written by Rebecca Clarke as well as a work entitled Morpheus, written by a certain Anthony Trent. As it happened, critics praised the work of Mr. Trent, while mostly ignoring the music written by a woman. As Anthony Trent was her pseudonym, the story illustrates the difficulties that Ms. Clarke experienced at a time when prejudice against women musicians was still appallingly strong. She would continue her career as composer intermittently, sometimes interrupted by her performing work, sometimes by discouragement at the obstacles in her path as a woman in a man’s world. Though she did achieve some measure of recognition, many of her works, including Morpheus, were published only after her death and much of her music is still unpublished.

As mentioned above, in 1944 on a street in Manhattan she met her old acquaintance James Friskin. They married and, by all accounts, lived happily ever after although, despite encouragement from her husband, Clarke mostly gave up composition.

Morpheus is a reference to the Greek god associated with sleep and dreams, and it would be hard to imagine a more dreamily sensuous evocation of his realm. As a virtuosa herself, Ms. Clarke knew how to extract the most voluptuous sounds from the viola, accompanied by sensuous chords and beautiful coloristic effects in the piano, including trills and glissandi. Morpheus is a small masterpiece of Impressionist style, in which the composer shows the influence of composers such as Debussy and Ravel, but also a strong artistic personality of her own.

Those who believe that the long arc of the moral universe eventually bends toward justice can take some comfort in the fact that in these more enlightened days when women composers have become an important part of our musical life, there has been renewed interest in Clarke’s works. In 2000 the Rebecca Clarke Society was established at Brandeis University to promote her music.