1945: At War’s End – “Remembrance”

On November 4 and 5, Guarneri Hall commemorates the terrible finale of the end of World War II, the worst global conflict in human history. The November 5 Remembrance program showcases music by three composers who knew firsthand the human devastation wrought by the war and could not let it be forgotten: Michiru Ōshima, Dmitry Shostakovich, and Benjamin Britten. Refusing to turn away from the horror they had seen, they raised their own voices in memory of the voices that had been so cruelly extinguished.

Stories of the Survivors

There are moments in time when the world is remade. Sometimes their significance is not obvious. We may look back and identify an event that triggered far-reaching and unforeseen changes, gaining momentum over decades and even centuries; the invention of the printing press comes to mind. But there are also watershed moments, when a new reality is shockingly, immediately apparent.

By mid-1945, Europe and much of Asia lay in physical, spiritual, and economic ruin, cities and countrysides devastated. An estimated 70 to 85 million people had died in combat, by genocide, or from disease and starvation. Another 55 million in Europe alone, and even more in Asia, were left homeless, malnourished, and destitute. Warfare, state-sponsored mass murder, ethnic cleansing, persecution and torture, the atomic bomb and its dreadful aftermath — the scale of death and suffering was vast and unprecedented. Those who survived knew that the old ways of life were destroyed forever, and the belief in human goodness profoundly shaken.

Guarneri Hall’s Remembrance program explores the musical memorialization of grief by three who felt compelled as survivors to tell their stories through their art. As Italian writer and Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi asserted, “Even in this place one can survive, and therefore one must want to survive, to bear witness.” Each composer created a document of memory — not a recounting of events, which music cannot accomplish, but of pain and sorrow. When we hear their laments, their memories become ours.

Michiru Ōshima (b. 1961), Memories, composed 2013

David Neuman, an ethnomusicologist who studies the use and purpose of music in culture and society, has called music “the crucible in which time and its memories are collected, reconstituted, and preserved.” Music evokes and retells the past in ways that make it meaningful for the present. A body of folk songs can constitute musical memory: immigrants bringing their songs to a new land and teaching them to succeeding generations, for example, can preserve cultural identity within a new reality. After war or other trauma, the same musical memory can be therapeutic, a record of how cultural identity can be rescued, revived and rebuilt.

But when the scale of devastation is immense, and the suffering unimaginably horrific, as with the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, how might music attempt to process such a traumatic memory?

Michiru Ōshima, born in Nagasaki, began music study as a young child. Her first musical influences were the Beatles, jazz, and the soundtracks of Disney and Akiro Kurosawa films. But hearing a rock band’s arrangement of Tchaikovsky when she was 17 inspired her to write her own symphony titled “Orasho” at the age of 18 and to pursue music professionally. After graduating from Kunitachi College of Music with a degree in composition, she entered the field of commercial music production and rose to fame with her scores for the three Godzilla films of Masaaki Tazuka (2000-2003). Her music is little known in the U.S., yet she is well-known and highly regarded in Asia. She has written more than 100 movie and anime scores, over 200 television scores, music for numerous popular video games, and several musicals. She has released over 300 CDs and earned eight nominations for the Japanese Academy Award for Music, winning it in 2008. Ōshima’s work in the classical style includes four concertos, two symphonies, and tone poems.

Ōshima’s body of work includes two pieces that commemorate the bombing of Nagasaki, A Thousand Cranes and For the East, neither of which would have been suitable for performance in Guarneri Hall. For tonight’s program we chose her solo violin work Memories for its yearning melody and poignant emotion.

Memories was commissioned by violinist Hilary Hahn as a part of her In 27 Pieces project, a CD of miniatures for violin and piano by composers from around the globe, through which Hahn aspired to reinvigorate the genre of the encore. (The recording won the Grammy Award in the Best Chamber Music category in 2015.) Although Memories does not explicitly commemorate the events of 1945, it is conceivable that for Ōshima, who grew up in Nagasaki, nuclear holocaust casts a shadow on each act of remembering.

The pensive, sorrowful melody that opens Memories seems to search for peace and happiness as it ascends and grows restive. This melody gives way to an agitated, dissonant section of painful memories. When the music of the opening melody returns, it retains disturbing remnants of the previous unrest. A lyrical cadenza for the violin helps the piece regain composure and perhaps contentment as it draws quietly to a close.

Dmitry Shostakovich (1906-1975), Trio No. 2, Op. 67, composed 1944

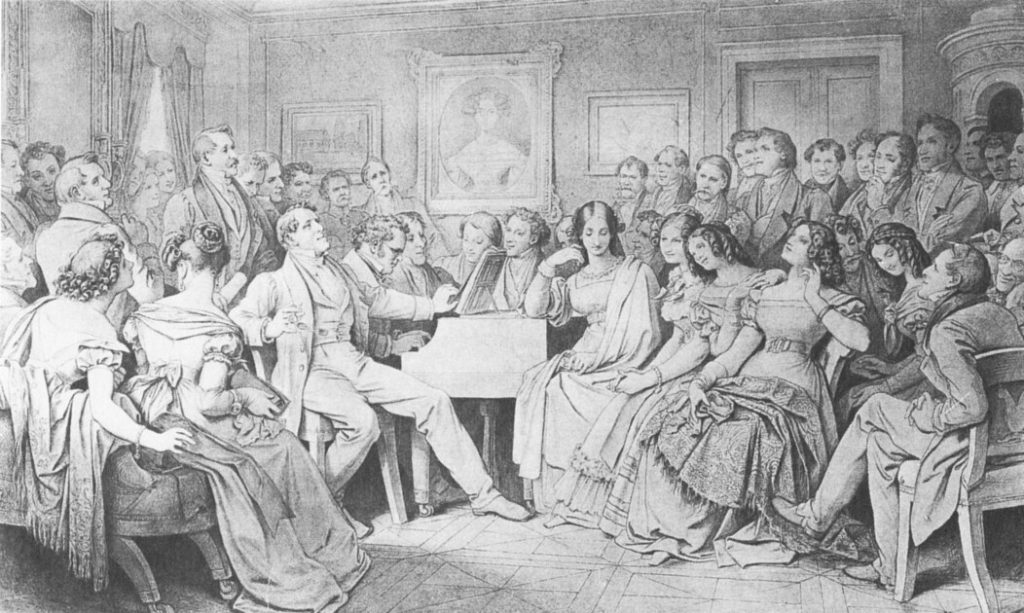

On November 28, 1944, Shostakovich’s Piano Trio No. 2 was performed in Moscow, the center of the Soviet state, by the same musicians who had premiered it in Leningrad two weeks earlier. Rostislov Dubinsky, founding violinist of the Borodin Quartet, recalled the occasion in Stormy Applause, his memoir of music-making under Soviet rule. “The music left a devastating impression. People cried openly. The last movement by popular acclaim had to be repeated. Shostakovich repeatedly came to the stage to bow. After that performance it was forbidden to play the Trio. Nobody was surprised. Officially the Trio has no program. But does this not say that what it expressed had been heard and understood?”

Indeed, two different messages were clearly received. The fourth movement’s Jewish flavor elicited the grieving audience’s heartfelt and perhaps cathartic response. But it also triggered immediate condemnation by Soviet authorities, who had decreed in the name of socialist realism that Soviet composers express only simple, heroic, and beautiful images of Soviet life. Public tributes to victims of tragedy may meet with universal approval, as did Shostakovich’s own Leningrad Symphony, which lifted and inspired besieged citizens with its optimistic, powerful conclusion. But public tribute can be dangerous when paid to people deemed unwholesome or subversive to the social order — in other words, unworthy of grief.

Throughout his career Shostakovich had at times been honored by the Soviet regime, but his music had also been publicly and humiliatingly censured, banned for being too modern, too dissonant, or too complicated. In 1936 Stalin himself labeled his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District as immoral Western decadence, which so demoralized and frightened Shostakovich that he never composed another opera. With the incorporation of Jewish elements in this Trio, Shostakovich, an atheist and non-Jew, had opened himself to attack on yet another front.

Jewish culture occupied an ambiguous and perilous position in the Soviet Union, which Stalin defined as a state consisting of individual nations unified by socialist ideology and bound by friendship and mutual trust. But Russian Jews did not possess a common language, traditions, or territory of origin, sharing only a religious practice, so to the Soviets they were not a nation at all. They could never be assimilated into the state as a group and thus made a convenient object of persecution. Jewish music was viewed contradictorily, sometimes acceptable because of its clear and simple identity, and sometimes undesirable and anti-Soviet. Musicologist Richard Taruskin identified the double standard: “For Weinberg to write in a Jewish style meant staying put in his ghetto. For Shostakovich to do it meant making common cause with enemies of the people.”

In this Trio, Shostakovich embedded Jewish themes in his music for the first time. He constructed a complex of commemorative elements, each embodying an aspect of Jewishness. The first was his dedication of the Trio to his closest friend, Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky, whom he had known since 1921 and whose sudden death in 1944 nearly broke him. “I have no words with which to express the pain that racks my entire being. It is very hard to bear.” Sollertinsky was a musicologist, linguist, teacher, and artistic director of the Leningrad Philharmonic. In 1934 he introduced Shostakovich to Mahler’s music and was directly responsible for the Mahlerian features and tone of Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony, as well as for Shostakovich’s increased focus on symphonic composition in the 1940s. In 1936 he publicly defended Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth, for which he too was attacked in print. The Soviet regime would never forgive his crime of infecting Shostakovich’s music with the Western decadence of the Jewish Mahler and other modernists.

The second commemoration Shostakovich inscribed into his Trio was that of his favorite pupil, Veniamin Fleishman (1913-1941). Fleishman studied with Shostakovich in the late 1930s in Leningrad. At Shostakovich’s suggestion he had begun writing an opera based on Chekhov’s Rothschild’s Violin, the story of a Jewish coffin maker and violinist. When the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, he left school and joined the Red Army; weeks later he was killed. In 1943 Shostakovich, learning the young man’s fate, obtained Fleishman’s manuscript and by February 1944 had orchestrated the entire vocal score and composed the set of variations with which it ends. Despite Shostakovich’s efforts to get the opera published and performed, it would not receive a staged production until 1968. After one performance, however, it was suppressed, its Jewish subject matter considered “Zionist.”

Rothschild’s Violin was Shostakovich’s first close encounter with the modes, rhythmic inflections and klezmer style of Jewish music. Shortly afterwards, he would incorporate these elements into his Piano Trio. At the time he was writing the Trio, horrific reports of Nazi atrocities in the death camps of Treblinka and Majdanek began circulating in the Soviet press. Shostakovich never confirmed that these reports were his impetus for writing the apocalyptic-sounding finale, but it is hard not to agree with the many who believe that the movement, desolate and desperate by turns, is the sound of Shostakovich mourning the murdered Jews.

Shostakovich was far from finished with remembering the Jewish dead in 1944. The Trio represents the first expression of the Jewish character that would ring in his musical voice for decades, in the Violin Concerto, the song cycles From Jewish Folk Poetry and Four Monologues, the Fourth and Eighth String Quartets, the Prelude and Fugues for Piano, the Cello Concerto, and the monumental Symphony No. 13 “Babi Yar.” Shostakovich would in ever more public and transparent ways honor those who must not be grieved, keeping the memory of their suffering alive through his music and ensuring that it would resonate in the world long after he himself had passed.

At the time he composed the Op. 67 Trio, between December 1943 and August 1944, Shostakovich was living in Moscow. Leningrad, his home, had been under siege since the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. At first Shostakovich refused to abandon the city but was finally evacuated on October 1. Despite the chaos and disruption of siege, evacuation, and relocation, his fierce determination to persevere kept a stream of new works flowing steadily from his pen for nearly three years, until the shock of Sollertinsky’s death in February 1944 stopped him in his tracks. With the Trio already partially written, he decided to dedicate it to his dear friend’s memory, but it was months before he emerged from his despair and regained the drive to compose again. He returned to the Trio in June, completing it within two months. Its first performance took place on November 14, 1944, in the Great Hall of the Leningrad Philharmonic — a fitting tribute to Sollertinsky, the Philharmonic’s artistic director for many years — with Shostakovich himself at the piano. Shostakovich recorded the Trio twice: in 1946 with violinist Dmitri Tsyganov and cellist Sergei Shirinsky, who had premiered the work with him, and in 1947 with violinist David Oistrakh and cellist Miloš Sádlo.

I. Andante – Moderato – Piú mosso: The movement opens like an eerie premonition of disaster, made only more menacing by the piano’s low register. Nervous repeated notes in the strings background the piano, now in the high register, as it energizes the opening theme. The violin introduces an almost-cheerful melody which is soon disrupted by cello and piano. The mood alternates between irritated outbursts and furtive intensity, building to an angry climax before evaporating strangely.

II. Allegro con brio: This grotesque waltz shatters the mysterious aura with its aggressive stomping, whining and sneering gestures. The boisterous middle section in the major mode provides scant comedic relief before the waltz returns, sounding even more menacing.

III. Largo: Blood-curdling thick chords in the piano present the passacaglia, the repeating pattern that will obsessively control the progress of the movement. Above it the violin and cello intone a lament that becomes more insistent and unhinged, finally sinking into complete depression.

IV. Allegretto – Pesante – Adagio: The stark detached sound world of the finale, a macabre Jewish dance, enters without a break, in another bizarre juxtaposition. The menacing dance builds to a hysterical fury and then unravels into a ghostly restatement of the opening until the solemn chords of the third movement reappear like the tolling of funeral bells. In the words of Dubinsky, the trio ends with the Jewish motif “disappearing into non-existence like a question mark about the fate of the whole nation.”

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976), String Quartet No. 2, Op. 36, composed 1945

It is not always helpful to discover the meanings in a musical work by mapping it onto the circumstances of the composer’s life, or to simply assume that work reflects life. Beethoven, Fauré, Mahler, and many others wrote luminous, optimistic music in times of great personal suffering. Nevertheless, noticing points of correspondence between life and music can yield food for thought, and one interesting thought arises with Benjamin Britten: return and memory preoccupied him. He returned throughout his life to writing music based on the principle of return: the passacaglia, in which a piece is built upon a musical foundation that constantly recurs, and the variation set, in which a theme is successively altered but always returned to.

Britten himself was a homebody. He made his home in the English county of Suffolk where he was born and died; after his periodic travels to London, America, Germany, and on concert tours, he always returned and wrote most of his music there. “I do not write for posterity. I write music, now, in Aldeburgh, for people living there. My music now has its roots, in where I live and work.” The impulse of both the musical form and the homebody to return to their roots matches the dynamic process of memory, which always returns to its source, constructing and reconstructing the past in order to shape the future. And what Britten saw on his trip to Germany in 1945 was a horror he could not forget.

Britten was a lifelong pacifist, earning him vicious criticism during the 1940s. With his partner Peter Pears he had left England for America in 1939, alarmed by the growing fascist threat and seeking new inspiration for composition. When England entered the war, he was publicly excoriated as a coward who had fled to America instead of fulfilling his duty to serve in the army. He returned home in 1942, not to fight but to pursue the opportunity to write his first opera on an English subject (Peter Grimes) and thereby find a way to contribute to English musical culture. He received official status as a conscientious objector and for the next three years performed non-combatant duties, working for the BBC and giving recitals around the country to boost morale and promote English culture, and working for the BBC. In July 1945, just after the end of the war, he met the violinist Yehudi Menuhin, who was about to embark on a recital tour of war-torn Germany, performing in sites where the liberated death camp prisoners were housed. Britten begged to join Menuhin on the tour and the partnership was born.

Britten never shared why he was so adamant to join Menuhin, who later stated that it was because of Britten’s “profound sense of community with the suffering world.” It was Menuhin who described the “appalling state” of their audiences, “men and women dressed in blankets, desperately haggard and many still ill.” Nor could Britten speak about what he experienced, only referring briefly to it as “horrific” and “harrowing” without elaboration. But late in life he confided to Pears how the memory of the victims and their desolate surroundings had colored everything he had written subsequently.

What might have engendered in Britten, the homebody who for the most part lived a comfortable middle-class life, the profound sense of community with the suffering world that Menuhin perceived, causing him to be shaken so deeply? Despite his love of home and the solace he found there, Britten was in some ways an outcast in his community and would never be fully accepted. Cruelly criticized and ostracized for his open homosexuality, his pacifism, his early professional successes, his modernist aesthetics, and his intellectual brilliance, he knew well the dark side of home. He would express this dichotomy in his Quartet, Op. 36, through the polarity he established between the major and minor modes (major in the first movement, minor in the second, and the eventual restoration of major in the last). The chasm between the home Britten remembered and the reality of isolation would never be breached.

The Quartet No. 2 was one of three works Britten composed to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the death of Henry Purcell, whom Britten considered the “last important international figure of English music” and a powerful musical model. The other two were the Holy Sonnets and The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra. The quartet was commissioned by and dedicated to his friend Mary Behrend, to whom he wrote, “To my mind it is the greatest advance I have yet made.” It received its premiere on November 21, 1945, in London.

I. Allegro calmo, senza rigore: The first movement is “calm and free,” in the character of a fantasy, a dynamic form characterized by changing moods and textures that was a mainstay of the era of Purcell. The opening gesture, with its wide, almost ecstatic melodic leap, serves to announce the beginning of each new section. It functions in this manner as the basis for a series of five variations, each with a different character and possessing a unique sound environment. The movement culminates in the final section, which combines all the versions of the theme over the cello’s arpeggios before the delicate coda.

II. Vivace: This dark and anxious scherzo recalls the sound world of Shostakovich, with strings muted throughout the movement. Distinct melodic lines emerge from the texture to make the imitation between voices clearly audible. Sometimes dance-like, sometimes machine-like, the movement boils over with nervous energy that plays itself out in an uncertain conclusion.

III. Chacony. Sostenuto: Here the homage to Purcell is obvious: Chacony is an ancient term for the repeating form of the passacaglia. Britten crafts 21 variations in three groups of six but disguises the sectionalism of the variation form. Each group concludes with a brilliant cadenza by a solo instrument: first cello, then viola, and finally violin. The boundaries between variations are indistinct, each building to its own conclusion, so the cadenzas provide a sense of structure as well as articulate the evolution throughout the movement. Here the dichotomies between harmony and dissonance, lyricism and agitation, imitation and unity, and solo and ensemble textures are fully exploited. The final three variations form a majestic apotheosis in which massive C Major chords resound 21 times.

Linda Berna