Sun | Moon Program Notes

As Guarneri Hall joins scientists around the world in celebrating hydrogen — the most abundant element in the universe — on its dedicated day, two timeless celestial bodies will take center stage: our sun and moon, long revered, mythologized, and used to mark the rhythms of human life. The sun, whose immense energy is fueled by hydrogen, releases the light that orders the cosmos and is essential to our lives. The moon, now known to be a source of hydrogen as well, also gives light and influences earth’s rhythms. Guarneri Hall’s Sun | Moon program showcases the music of composers who have drawn inspiration from the movements and brilliance of the sun and moon, and all that they symbolize in human thought.

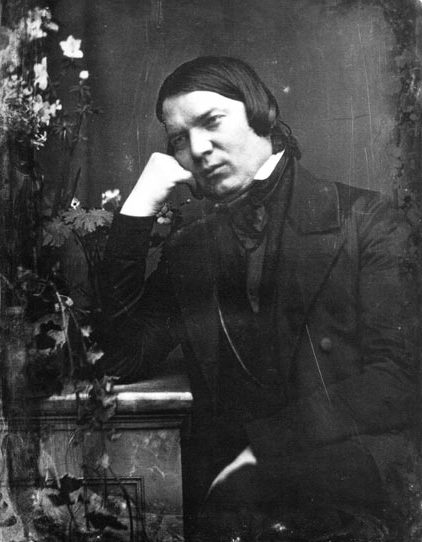

Robert Schumann (1810-1856), Gesänge der Frühe (Songs of Dawn), Op. 133, composed 1853

In early 1854, Robert Schumann wrote to the publisher Friedrich Arnold about a collection of five piano pieces titled Gesänge der Frühe that he had recently completed. He described them as portraying “the sensations engendered by the approach and gradual emergence of morning, more from the perspective of an expression of feeling than of tone-painting.”

Sunrise has always symbolized new beginnings and renewed life force. It seems significant that its image of hope and possibility appealed to Schumann during the last several months of 1853, when he appeared to be breaking out of a period of personal and professional darkness. In a burst of creative energy, he had completed six major works in quick succession: Gesänge der Frühe, the Phantasie for Violin and Orchestra, the Violin Concerto, his third Violin Sonata, Five Romanzes for piano, and the chamber trio Fairy Tales. During this time, he was also thrilled by his first visit with young Johannes Brahms, who he believed was destined to lead music to its “highest and most ideal” expression. However, the conventional view of Schumann’s output from his last years has been negative. The music is seen as confused and awkward, the work of one with nothing left to say. What accounts for the dismissal of Schumann’s late music are likely the events that would follow in early 1854: his psychotic breakdown and confinement to a mental asylum until his death two and a half years later. His late music is tainted by the shadow of his illness.

Schumann’s artistic path was never smooth. In 1830 he had abandoned the study of law (which he was pursuing under family pressure) to devote himself to the musical and literary interests that had engaged him since boyhood. To achieve his goal of becoming a concert pianist, he moved in with the noted pedagogue Friedrich Wieck, who demanded a regimen of daily lessons and supervised practice. There he met Wieck’s daughter Clara, a virtuoso in her own right and a musical kindred spirit (Robert and Clara would later engage in an ugly five-year battle against her father for permission to marry).

But disenchanted with Wieck’s teaching and plagued by lameness in one of his fingers, he gave up his dream of concertizing and left Wieck’s household, refocusing his energy on music criticism while publishing his first works for solo piano. In 1834 he founded the Neue Leipziger Zeitschrift für Musik (New Leipzig Music Journal), in which he revolutionized music criticism by employing imaginary characters with different personalities to describe and assess music in poetic terms. In the last half of the 1830s, he produced some of his most beloved and best-known works for the piano: Carnaval, the Fantasy, and Scenes from Childhood. Schumann did his best to keep working, but nervous disorders and depression began to intrude upon his spirit.

By the late 1840s, Schumann enjoyed wide acclaim for his dual accomplishments as composer and writer. In 1840 he and Clara had finally married, sparking an effusive year of song composition in which he wrote well over 100 lieder. By the end of the decade, he had produced two symphonies, a symphonic poem, a piano concerto, much chamber music, and reams of choral part-songs. Having sold off the Neue Zeitschrift in 1844, he poured his literary efforts into work on two grand oratorios for soloists, chorus, and orchestra, and an opera. However, the need to provide for his family amidst periods of inactivity caused by depression led him to seek a salaried position, so in 1850 he became the municipal musical director in Düsseldorf. The situation started well. But further deterioration of his psychological and physical health and his aversion to the socializing required by such a post led to conflicts with the musicians and ultimately to his resignation in October 1853. The creative resurgence that followed was short-lived. In February 1854, visual and auditory hallucinations and a suicide attempt consigned him permanently to the asylum.

What have been the barriers to appreciating Schumann’s late music? Clara herself described the Gesänge der Frühe as “very original but hard to understand” and “very strange.” Yet she had leveled a similar complaint at Schumann back in 1839: “Listen, Robert, couldn’t you just once compose something brilliant, easily understandable, a completely coherent piece?” Indeed, some of the so-called deficiencies in the late music appear in his earliest works — the tendencies to juxtapose diverse characters, to avoid closure, to mix genres, to adopt an epic tone rather than dramatic development, to assemble montages of smaller pieces as different aspects of an overarching theme — while the same subdued, introspective, and fragmented qualities criticized in late Schumann ironically have been praised as “transcendent” in late Beethoven. As Swiss composer and Schumann champion Heinz Holliger stated in 1998, “Bearing mental illness like the mark of Cain, Schumann, more than all other composers, is susceptible to misunderstanding. Certain works of his early and middle period are praised to the skies, while a pious veil of silence obscures the more sober, austere and concentrated works of the late period.”

Recent reappraisal of Schumann’s late music has led us away from conflating his creative products and his psychological state. A more sanguine approach to these five pieces, each with a unique character, varied moods and muted, peaceful ending, allows us to recognize in them images of dawn expressed by one who has lived long and endured much, yet meets the new day with optimism and calm acceptance.

In a tranquil tempo opens with a skeletal rising melodic figure that does not conclude but is immediately repeated, fully harmonized. The repetition does not conclude either but leads to a reprise of the opening in a different tonality. Likewise, the second statement of the opening fails to conclude and moves to yet another tonal region. The opening reprises a third time, continues with even richer harmonies, and flows into a fourth reprise that climaxes in the high register with the fullest sonorities yet heard: the moment of sunrise. Then day breaks, and sunlight gently suffuses the world. The overlapping phrases and varied tonal colors suggest the sky’s changing appearance as the sun’s rays grow stronger. The constant parade of new beginnings is opposed by delaying closure until the final bar; this piece is one long phrase just as sunrise is one continuous process.

Lively, not too fast is capricious and improvisatory. It seems to begin in mid-thought; the ear searches for both a downbeat and a key. The widely spaced opening figure soon recedes into the background; dotted rhythms assert themselves briefly before softening into playful triplets. The opening texture returns unexpectedly, more fully voiced, and a delicate filigree of a melody emerges in the highest register. Each of the different rhythmic and melodic characters make their final appearances as the piece winds down to a gentle finish. It is as if the sun that just rose has shined its light on the diversity of the world – we are delighted by all we could not see in the dark of night.

Spirited is the longest and most serious of the set. Obsessively taking up the dotted rhythms of #2, with full chords leaping up and down the keyboard in unpredictable fashion, it searches angrily for a key in which to settle, finally arriving in F# Major after a long 17-bar stretch only to begin the search anew. No melody or regular meter emerges from the fierce chords; only the insistent dotted rhythms carry us forward to a furious climax. The sun’s heat is powerful now! Yet immediately and curiously the music grows calm, finds the home key of A Major, and closes softly.

Agitated continues in unsettled fashion; fitful arpeggios underlie an impassioned melody in the minor mode. The repeated gesture of the melody, reaching up to the high register, seems to yearn toward something without finding it, then suddenly and briefly adopts a playful disguise. When the yearning melody returns, its unrest has eased and it ends gently in the sunnier major key.

Peaceful at the beginning, progressing to a stirring tempo recalls the first piece with somber chorale-like opening. This time, however, the chorale phrase closes after one statement and immediately begins a variation in a new key with more active rhythms, expanded range, and loud sonorities. Out of this new character a long-breathed melody emerges, evolving from but not repeating the opening chorale. This melody sinks to the low register and grows in power over a span of 8 measures to a triumphant climax. But as we have come to expect, the piece soon returns to simplicity, a tender reflection on all that has come before.

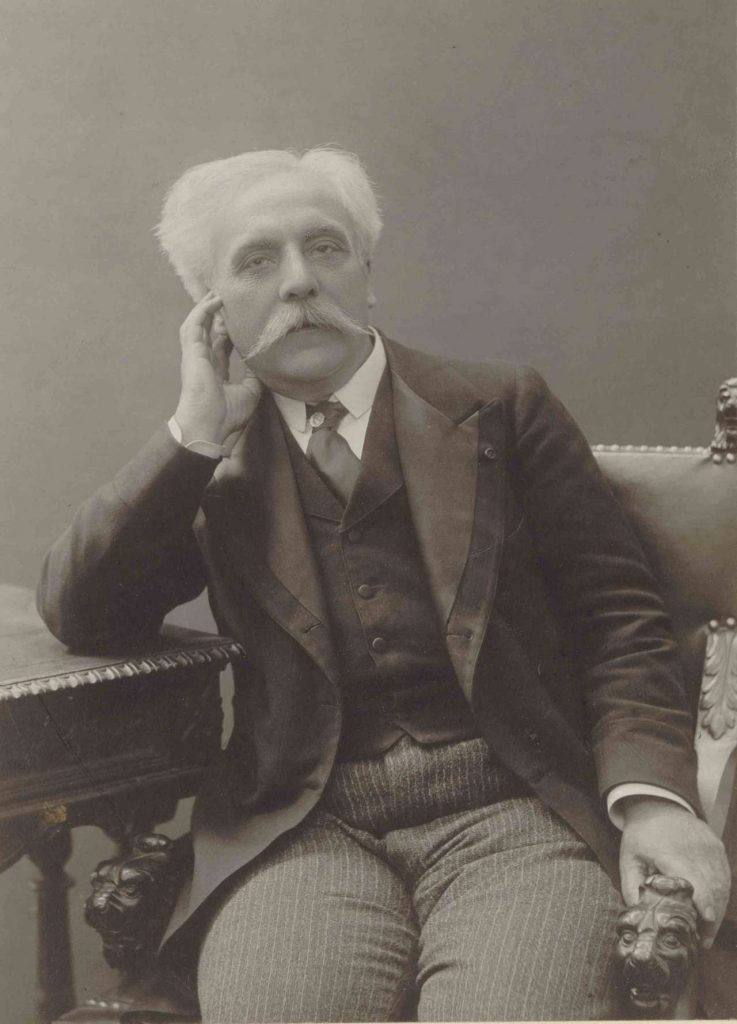

Gabriel Fauré (1848-1924), La Chanson d’Ève (The Song of Eve), Op. 95, on poetry by Charles Van Lerberghe, composed 1906-10

In La Chanson d’Ève, Gabriel Fauré composed the story of the first woman, creating a luminous world out of time that both brings the sun to life as a character in her garden, and draws on the symbolic meanings associated with it: rebirth, vitality, and power.

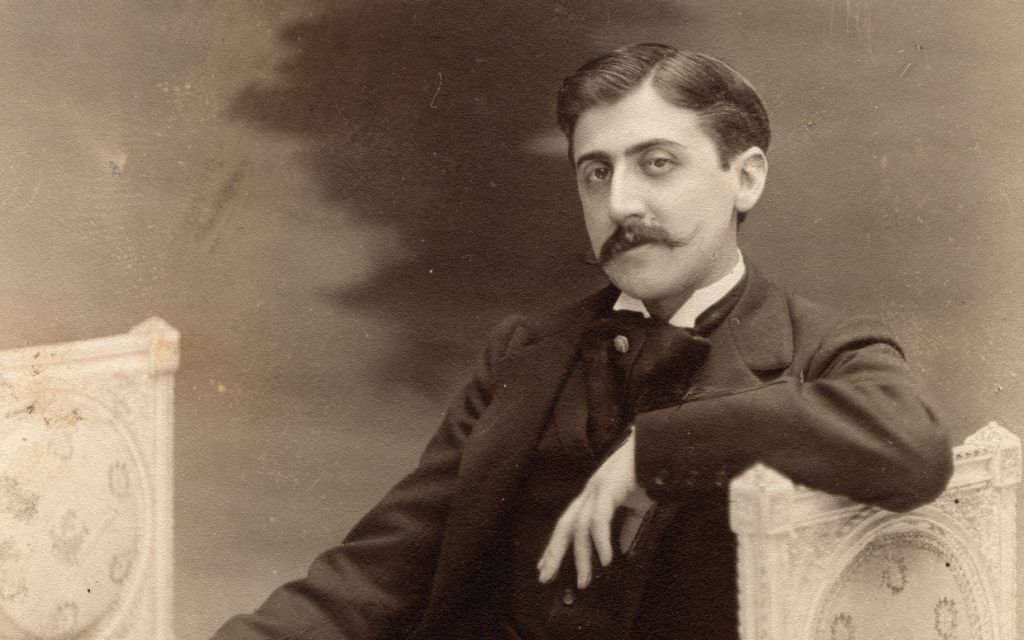

The history of French song is unthinkable without Fauré, widely considered its greatest master. Fauré’s three important song collections and five song cycles dating from the 1870s to the 1920s lie at the heart of the transformation of the genre that occurred during the late 19th century: from sentimental romance to mélodie, the marriage of French music and French poetry to form a medium for intimate and profound expression. Over several decades, composers and poets strove to bring words and music into a closer, more meaningful relationship. Poetry aspired to the sonorous qualities, freedom of construction, and limitless suggestivity of music, while song aimed to emulate speech and abandoned accompaniment in favor of evoking poetic meanings with musical analogues. La Chanson d’Ève realizes these ambitions in the most moving and poignant ways.

Fauré cultivated close relationships with the writers of his era, and it was through his engagement with Maurice Maeterlinck’s drama Pelléas et Mélisande that he encountered Maeterlinck’s friend, the Symbolist poet Charles van Lerberghe (1861-1907). Symbolism, having originated in France and Belgium in the late 19th century, rejected description, statements of emotion, and regularity in favor of imprecise imagery, ambiguous symbols, metaphor, and free verse; its goal was to suggest, not define. La Chanson d’Ève, published in 1904, numbers 96 poems and is considered van Lerberghe’s finest work. It essentially rewrites the story of creation by placing Eve in charge, omitting Adam, and portraying God as a presence in nature rather than a supreme being, reflecting van Lerberghe’s view of Christian theology as a myth to mine for poetic content.

The creation of La Chanson d’Ève stands at a nexus of new beginnings for Fauré. For almost 40 years, his life had consisted of constant work as an organist and choir director, combined with a heavy private teaching schedule, writing concert reviews, and networking in musical salons to make artistic and professional connections. Intense compositional activity consumed whatever time was left. Then in August 1905 he was elected to the Directorship of the Paris Conservatoire, a full-time position that validated his status as an artist and enabled him to quit his job as chief organist at the prestigious Madeleine Church, which he had come to resent as a burden. Fauré seized the opportunity to immediately begin reforming the curricula of the Conservatoire, instituting required courses in music history and expanding vocal training to include study of the lieder of Schubert and Schumann. That in turn inspired him to begin a new song cycle of his own, his first in more than 10 years. For that cycle he chose La Chanson d’Ève by van Lerberghe, a writer he was setting for the first time but who would eventually inspire more songs from him than any other poet.

As Fauré’s son and biographer Philippe Fauré-Frémiet would recall, La Chanson d’Ève was “constructed little by little, piece by piece, without a prearranged plan, and with modifications to the order of the songs.” Fauré commenced work on it in the spring of 1906 with Crépuscule (Twilight), for which he repurposed material from the incidental music for Pelléas et Mélisande which he had written some years before. By June it was finished and he was eager to move forward with the rest, but it would take him nearly five years to complete the cycle. Numerous obstacles delayed his work on Éve: bouts of illness, other projects like his opera Pénélope that occupied his attention, and finally, the stress of running the Conservatoire. The heavy responsibilities of his academic post restricted his composing to the summer breaks. The last piece to fall into place would be O Mort. The order of the songs was not finalized until January 1910, after the manuscripts had been sent to the publisher. The cycle’s first performance took place on April 20, 1910, with Fauré at the piano, at the initial concert of the newly formed Société Musicale Indépendante.

Fauré’s Eve is not van Lerberghe’s Eve. The original 96 poems are divided into four chapters: First Words (Eve awakes and senses the world), Temptation (Eve seeks knowledge), The Error (Eve takes the forbidden fruit from the serpent), and Twilight (Eve perceives her mortality and an angel leads her toward death). However, Fauré has no interest in temptation, sin, or suffering. With the 10 poems he selected, he invented a radiant Eve, an innocent who rapturously engages with creation and embraces both the joys and sorrows of existence. Her companion is the sun, whose brilliance and warmth she depends on and confers with. Fauré further rearranges the poems to convey the narrative arc of her life, one cosmic day from sunrise to sunset. But at the last, even after the sunset that heralds her death, the gentle light of the stars guides her into the abyss.

Paradise is the longest song of the cycle; it both tells the story of creation and presents important features of Fauré’s musical environment. The vocal writing is chant-like, slowly paced with many repeated pitches and rhythmic values that support the natural stresses of spoken French, avoiding vocal virtuosity and remaining mostly in the middle range to enhance the intelligibility of the text. Phrase structure is irregular and harmony often obscure. Each verse displays a different character according to the action or situation it entails, achieved by varying the textures, degrees of activity in voice and piano, and loudness levels. Two melodic motives which will recur throughout the cycle are introduced. Motive 1 is the piano’s widely spaced ascending opening phrase that functions as a pronouncement, and Motive 2 is the narrow stepwise melody in the piano’s interlude after Eve sings “a blue garden blooms.” The moment that Eve’s voice itself blossoms, in the final line of the song, it does so together with this second song-like motive.

First Words. From this point on, we no longer hear the voice of God, only that of Eve. Her relaxed, free, melody parses into short irregular groups as she turns her attention from one sound or sight to another. The piano closely follows the voice line, as if her mind and the things she perceives in her garden are one and the same.

Passionate Roses features irregular short melodic phrases and nervous rhythms as Eve calls out, one by one, to the other life forms in her garden. The song can be felt in two parts. The first is more static and spare; Eve addresses the roses and the stars which do not move. The texture and melody become more active in the second part because the sea and the sun are both dynamic, moving things. As she praises her “radiant sun” the melody climaxes dramatically.

How God Shines opens with Motive 1. Eve’s excitement at the bright sunlight is revealed in the more active vocal line, which now contains large leaps and repeats the melody and high register of the previous song’s “radiant sun.” A new, sparkling texture in the piano signals the brilliant midday sun; this shift helps us feel the plot and the day progress within the song.

The White Dawn continues the shimmering effects in the piano and again uses the sun melody from songs 3 and 4 for the words “the sun is shining.” Eve’s voice is more insistent here. She takes the lead in propelling the song forward, as her entire being awakens to the light and the shimmering piano unifies the ideas of light, love, and her soul.

Spring Water truly “comes and goes ceaselessly” in this song. The oscillating scale passages in the piano are both meterless and keyless, and Eve’s voice remains calm, during the first two verses which speak of quiet pools. With the final verse, as the living water flows downstream to the sea, the scales are replaced by lively arpeggios and Eve raises her voice joyfully.

Are You Awake, My Fragrant Sun heightens the restlessness of the previous song with agitated tremolos and fast tempo as the light in the garden begins to wane. It is with a sense of fright, almost hysteria, that the singer’s melodic line rises in pitch and volume for the last half of the song, as Eve worries over the absence of sun, and wonders whether he sees her waiting for him.

Amidst the Scent of White Roses evening at last descends; there will be no more sun for the remainder of the cycle. Eve’s own voice too has literally been removed; the scene is described by a narrator. Eve is subdued, the mood resigned, and her melody is often surrounded by the texture of the piano part as she herself sits quietly in the garden. The piano’s bass line intones Motive 2 throughout; this had been associated with Eve’s singing, but now the singing voice only whispers.

Twilight foreshadows the end of Eve’s life. She hears the world sigh and weep but cannot yet grasp that it mourns for her. Motive 1 returns, restoring the quiet with which the world began. The motive dominates this song in the form of an ostinato, a repeated pattern around which the song is structured. Repetition here signifies the cycle of life and death that exists even in Paradise; all that lives will fade away. And perhaps she understands and accepts that her end is near, because Fauré closes the piece peacefully in the major mode, the repeating motive replaced by a complete scale.

O Stardust Death portrays Eve’s clear-eyed embrace of her death. The piano’s serene and sonorous chorale has no trace of anxiety and is rhythmically steady for the first time since Paradise. Again, Eve chants, raising her voice only once, not in song but to demand to be broken. The most beautiful gesture of the piece occurs in the last verse. Here Motive 2, Eve’s singing melody, is taken by the piano; in four successive statements it moves lower and lower in register as Eve disappears into the earth.

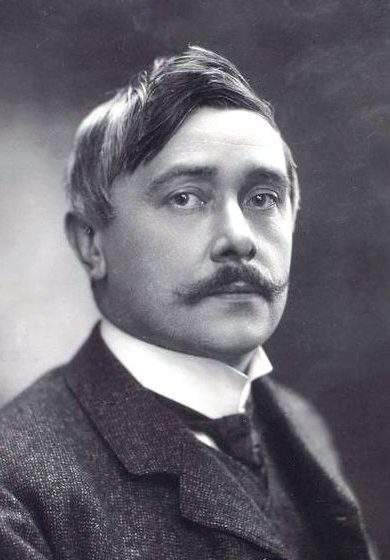

Jake Heggie (b. 1961), Songs to the Moon, on poetry by Vachel Lindsay, composed 1998

Jake Heggie’s Songs to the Moon is a collection of whimsical fairy tales taking place within the world of the child’s imagination. The cycle begins with a prologue that presents the moon as a magical gift, followed by seven fantasies about the moon from various perspectives.

Vachel Lindsay (1879-1931) was born in Springfield, Illinois. A central figure of the early 20th century Chicago Literary Renaissance (along with Carl Sandburg and Edgar Lee Masters), he wrote over 100 poems about the moon, varied in mood and rich in imagery. And this poet would likely have been sympathetic to Heggie’s self-professed goal as a song composer: “For me, every song is a drama of its own, to be performed as seriously as a scene from a play or an opera.” Lindsay himself believed that poetry was rooted in song, meant to be “chanted, whispered, belted out, sung, amplified by gesticulation and movement, and punctuated by shouts and whoops.” He is widely credited with helping keep the oral tradition of poetry alive. Known as the Prairie Troubador, he journeyed multiple times from coast to coast across the United States (sometimes on foot!), giving dramatic readings of his vivid, highly rhythmic poems.

Jake Heggie is one of America’s most prolific composers of vocal music. Dead Man Walking (2000), his first opera, is now the most-performed American opera of the 21st century. Heggie has since written 9 more full-length operas including Moby Dick (2010) and It’s a Wonderful Life (2015) and numerous one-acts, over 300 art songs, concerti, chamber music, choral and orchestral works. The recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship among other honors, he was named Musical America’s 2025 Composer of the Year and joined the San Francisco Conservatory composition faculty this fall.

Trained as pianist and composer, Heggie toured briefly as a concert pianist after graduating from UCLA. When the neurological condition focal dystonia curtailed his performing career, Heggie entered the field of public relations, working first for the UCLA Center for the Art of Performance and later for the San Francisco Opera. There he met mezzo-soprano Frederica von Stade, with whom he forged a deep friendship after gifting her with songs he had written for her. Heggie and von Stade developed a strong artistic partnership as well; they have collaborated in the creation of songs, operas, and choral works.

Songs to the Moon was commissioned for von Stade in 1997 by Music Accord, Inc., a consortium of presenting organizations. Together Heggie and von Stade agreed upon the theme of fairy tales and chose Vachel Lindsay’s poetry for the texts. The cycle premiered on a Ravinia Festival recital by von Stade and pianist Martin Katz on August 20, 1998, and was warmly received.

Prologue: Once More – to Gloriana is a gentle lullaby evoking the femininity associated with the moon, with its delicacy and emphasis of the high register and its cyclical nature. Two circular patterns that rise and fall recur throughout the piece: a widely spaced figure originating in the piano’s left hand, and the brief melody introduced by the singer. Another circular process results from the tradeoff between the performers in the last verse (“I bring you moons…”): the pianist plays the singer’s melody, and the singer intones the wide intervals from the piano accompaniment.

Euclid and his friends discuss a geometric representation of the physical world. Their music is metrically strict with regular four-bar phrases because they are serious thinkers, and jazz-inflected because they are sophisticated. Because they always look down, the first verse sits mostly in the middle to low registers. But the jazzy syncopated introduction opens the second verse an octave higher, soft and smooth instead of short and bouncy, then closes the piece an octave higher still, even more softly. Unlike the old men, the child looks up to the sky, re-imagining the music from swaggering jazz into reverie and the circle into the real round moon.

The Haughty Snail-King (What Uncle William Told the Children) illustrates the ponderous parade of the snail king and his entourage with its heavily accented chords, repeated gestures, slow tempo, frequent pauses, decelerations, and breaks. The bluesy yet labored strutting of the snails gives way to the king’s ridiculously operatic pronouncement, with music that is even more static to symbolize his slow thinking as he covets the brilliant moon for his crown.

What the Rattlesnake Said portrays an arrogant, deadly creature who sneers at the moon, sun, and all creation. The song is a tango: a highly stylized, sinuous dance with long pauses during which body positions are held tautly, punctuated by sudden turns — like the demeanor of the snake who awaits the chance to uncoil and strike. The music mirrors these physical qualities with its slowly winding melody, arpeggiated flourishes, rigid rhythmic structure, and sustained chords which slowly shift one pitch at a time to change the harmony in a very sneaky way. The moon hides behind a cloud like the prairie dog taking refuge in his hole; it is not wrong to fear the snake…

The Moon’s the North Wind’s Cooky (What the Little Girl Said) is a fanciful version of the cycles of the moon. The full moon wanes like a round cookie that is being nibbled bit by bit until it is gone; as a new moon-cookie is baked it rises and spreads to full size, only to be eaten again. The song opens like a children’s game, with singer and pianist clapping and chanting in sing-song fashion. As if enjoying the image of the wind eating the moon, the music breaks into a jazzy scat section; the clapping game returns as the child finishes the rhyme and the wind bakes a new moon. With the lunar cycle complete, the singer balances out the song by repeating the jazzy melody.

What the Scarecrow Said is static like the scarecrow, who can only move if the wind blows. The ascending scale passages of the accompaniment evoke mild breezes; they supply surface motion, but lead nowhere and emphasize no key, and the singer’s melody wanders aimlessly. When the wind picks up in the second verse (“I wave my arms…”) a moving line appears in the piano’s texture and the melody grows urgent, ascending to a high climax as the scarecrow orders the birds to serve him. With the wind spent in the third verse, urgency recedes and the opening vagueness returns, underscoring the scarecrow’s delusion that the moon is his prize.

What the Gray-Winged Fairy Said casts a magical spell with the striking of the fairy’s gong in the piano introduction and its regular recurrence throughout the piece. The poem draws a parallel between the gong’s beats that reverberate through the air and the moon’s face which grows brighter as the night descends. A melody that hovers between speech and chant enhances the mysterious atmosphere, while the repeated strikes of the gong chord organize the piece like a sort of ritual, providing the only tonal stability in this harmonically ambiguous song.

Yet Gentle Will the Griffin Be (What Grandpa Told the Children) is highly sectional, invoking the narrative arc and spooky effects of a ghost story told to children at night. The sections are delineated primarily by tempo. The opening “rather creepy” section serves as the introduction, only asking, “The moon?” We then launch into the longest section, “very fast and rather wild,” that describes the hatching of the griffin egg, interspersed with maniacal laughter and eerie moans. The “much slower, mysterious” third section’s weirdly oscillating piano part in the upper register follows the gentle baby griffin toddling across the sky. An outburst of mad laughter returns to shock us in the “fast” raucous postlude.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), Piano Sonata in C# Minor, Op. 27, No. 2 “Moonlight”, composed 1801

Adagio sostenuto

Allegretto

Presto agitato

No Western composer can equal the legacy of Beethoven’s mythic stature as an artist, fueled by the aesthetic and emotional responses to his most individual, boundary-breaking compositions such as the Third, Fifth, and Ninth Symphonies, and the Fourth and Fifth Piano Concertos. One such work that has captivated listeners (and performers) since Beethoven’s lifetime, inspiring their own imaginative reactions, is the Piano Sonata, Op. 27, No. 2.

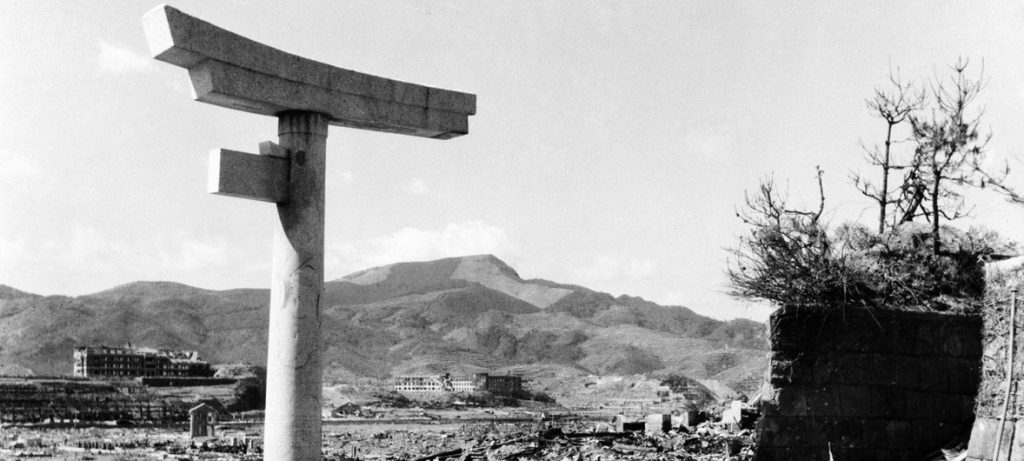

Its nickname of “Moonlight” was first given in 1823 by poet Ludwig Rellstab, who rhapsodized about its first movement, “The lake rests quiet under the light of the moon at twilight; the wave thuds against the dark shore.” By the 1830s the piece was being published under that name, and in the 1850s Beethoven’s biographer Wilhelm von Lenz wrote, “It is as if we catch sight of a colossal grave in the middle of a lonely plain, palely lit by the sickle moon.” Despite those who abhorred the epithet as silly and sentimental, the conceit stuck. Yet when we consider that the moon has always been linked to fantasy, the dream world, instability, and even madness, we do not find “Moonlight” so ridiculous. Beethoven’s own subtitle for this piece located it within the realm of the moon: he called it “Sonata in the manner of a fantasy.”

The ambitious Beethoven had arrived in Vienna, the musical center of the German-speaking world, from provincial Bonn in 1792. Over the next six years, after a brief period of study with Joseph Haydn, he worked to make his mark as a virtuoso pianist and composer. With the attitude that anything anyone else (including his esteemed teacher Haydn) could do, he could do better, with more novelty, grander scope, and more brilliance, he published a series of compositions designed both to show mastery of the important instrumental genres and to demonstrate his originality. This series included the piano trios, Op. 1, the string quartets, Op. 18, his first symphony, Op. 21, and the piano sonatas of Opp. 2, 7, and 10. These works appealed to the music-loving public, middle-class and aristocrats alike, and he soon gained patrons and admirers.

Then, having established his credibility as a musician and gained a following, in 1800 he embarked upon a new path, producing increasingly unusual and experimental works that are seen in retrospect today as leading toward his middle “heroic” period. One such experiment was the Piano Sonata in C# Minor, Op. 27, No. 2.

The standard way to open an instrumental sonata, symphony, or chamber work in 1801 was with the formal process also called sonata, a method of making a musical rhetorical argument. In a sonata, key areas and thematic ideas are first presented in opposition. The opposition is exploited through a stage of increasing fragmentation and instability labeled “development,” until finally the harmonic conflicts are resolved, and tonal unity prevails. Beethoven himself up until 1800 had followed this convention in all such compositions. But by labeling the work on tonight’s program a fantasy, he meant to convey that it was the product of imagination, not intellect.

Beethoven begins this fantasy-sonata with a moonstruck reverie that wanders like an improvisation through one key after another, maintaining the same static texture of hypnotic arpeggios, overlaid by enigmatic truncated melodies that sound alternately martial and pathetic and underpinned by mysterious tolling octaves in the bass. Beethoven scholar Joseph Kerman contends that its sadness will have overwhelmed “all but the stoniest of listeners” by the end of the first phrase. Such an opening was unprecedented and unsettling, the “normal” sonata experience having been completely undercut.

What could possibly follow this lugubrious yet compelling music? Indeed, Beethoven does not stop his experimentation there; he eliminates the differences in keys, characters and genres that typically appear in the sequence of movements. In the score he instructs the performer to proceed immediately to the next movement without pause and composes the second movement in the same key as the first, only in the major mode. But these methods of linkage are offset by a radical disconnect in tone: the second movement is a jaunty, rustic dance — a completely different mood that is hard to reconcile as a pendant to the first.

Beethoven continues to upend convention. The sonata movement that we expected at the beginning appears for the finale, but once again the character change is shocking: the last movement is furious, loud, and dramatic, staying in the home key but returning to the minor mode and recasting the gentle arpeggios of the opening movement as ferocious gestures. This makes the sonata feel like one long dream sequence encompassing three different scenarios, which concludes with a nightmarish climax. There is no denouement, no happy ending. The moon’s influence holds sway.

Linda Berna