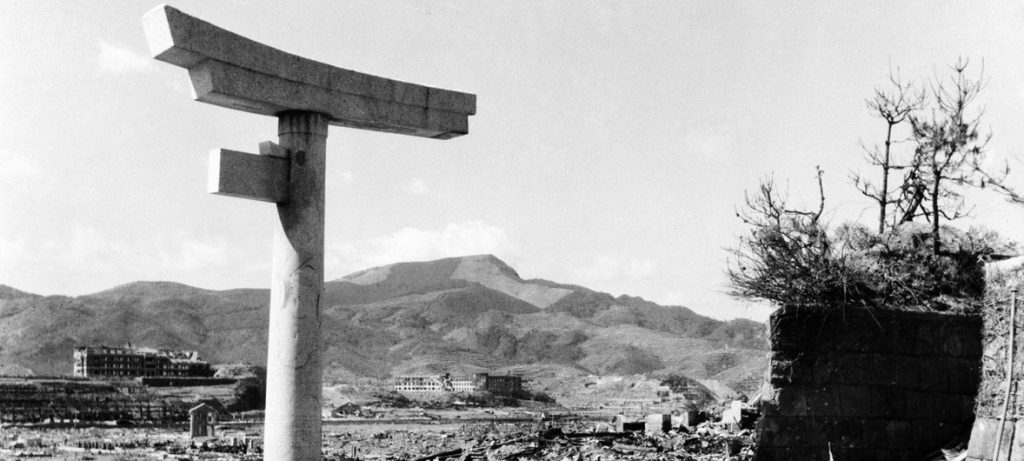

1945: At War’s End – “Resilience”

On November 4 and 5, Guarneri Hall commemorates the terrible finale of the end of World War II, the worst global conflict in human history. The November 4 Resilience program showcases music by three Central European composers, each with their own unique story of displacement by the war: Mieczysław Weinberg, Szymon Laks, and Bohuslav Martinů. Despite their harrowing experiences of persecution, exile, escape, and internment, in their postwar music we find a wellspring of resilience in the face of devastation.

Europe at War’s End

There are moments in time when the world is remade. Sometimes their significance is not obvious. We may look back and realize that an event triggered profound and unforeseen changes, gaining momentum over decades and even centuries; the invention of the printing press comes to mind. But there are also watershed moments, when a new reality is shockingly, immediately apparent.

By mid-1945, Europe and much of Asia lay in physical, spiritual, and economic ruin, cities and countrysides devastated by warfare. An estimated 70 to 85 million people had died in combat, by genocide, or from disease and starvation. Another 55 million in Europe alone, and even more in Asia, were homeless and destitute; “refugee” status became for the first time an internationally recognized classification. The weakening of the old colonial regimes sparked independence uprisings across Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. Predictably, political and military jockeying to fill the power void and assert dominance began at once, with the opposition between capitalism and communism rising to the fore. In Year Zero, his brilliant history of the war’s end, Ian Buruma recounts how, at the same time a conference of world leaders in San Francisco was crafting the Charter of the United Nations, pledging to maintain international peace and protect human rights, Soviet secret police tortured and imprisoned 16 members of the anti-Nazi Polish Underground and the French attempted with brutal force to suppress the Syrian independence movement.

In 1945, the ground had fallen away, and the old ways of life were shattered. It was for the survivors to find the way out of chaos, through a terra incognita fraught with turmoil and danger. Guarneri Hall’s Resilience program shares the creative outpourings of three such survivors, composers who suffered deeply yet refused to be crushed by the war’s horrors and aftershocks. Music, as many have cautioned, cannot make people more humane or more peace-loving. It can neither prevent war nor erase its damage. But music’s restorative power is real. It has always been a means to process individual and collective pain, and to affirm the human capacity in defiance of that pain to hope, imagine, and create. These composers persisted in making music because they believed, despite the ravaged world around them, that there was a future worth fighting for.

Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959), Czech Rhapsody, H307, composed 1945

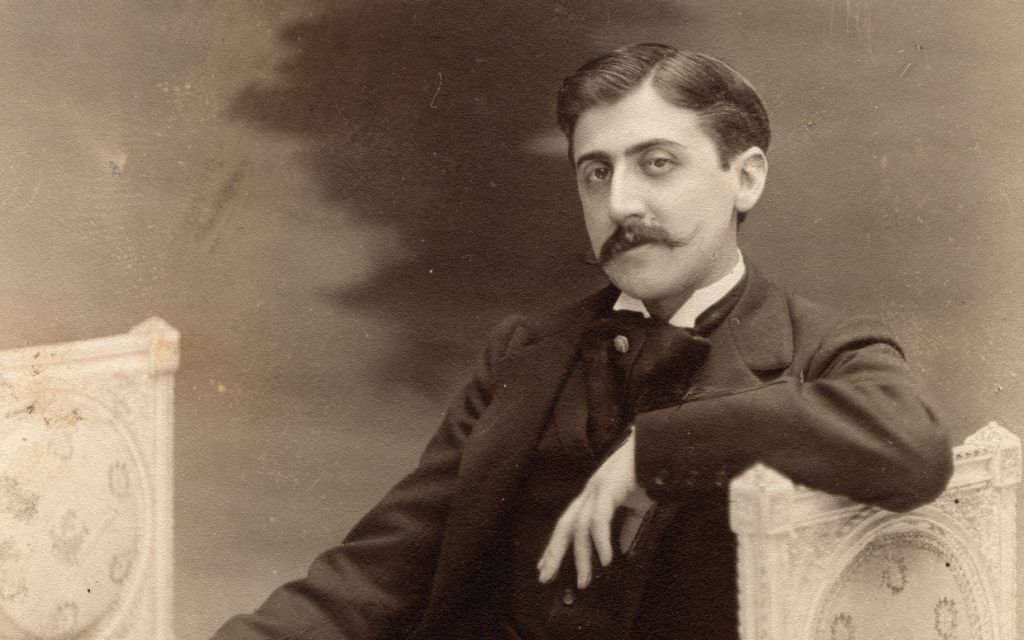

“Irresistibly original, irresistibly Czech” — so the Czech conductor of the BBC Symphony, Jiří Bělohlávek, praised the music of Bohuslav Martinů. Tremendously disciplined and prolific, Martinů produced more than 400 works in every genre from the time he devoted himself to composition in his late 20s until his death at age 68, including 16 operas, 15 ballets, over 70 orchestral works, film scores, songs and cantatas, and pieces for solo and duo piano.

Martinů’s chamber music output was extensive and unique. Besides pieces for standard groups like string quartet, he wrote for quirky combinations: clarinet, horn, cello, and snare drum; theremin, oboe, string quartet, and piano; 5 recorders, clarinet, 2 violins and cello. The latter type shows his extreme sensitivity to tone color and the penchant for unusual sonorities that we hear in all his music and which he later traced back to the unique sonic world of his childhood. Martinů was born in the bell tower of St. Jakub Church in Polička, Bohemia, where his family lived until he was 12 because his father was the town bell ringer and watchman. A shy child, he spent most of his time in the tower, listening from high above the town as the sounds below mingled with the tolling of the bells. “It was this space that I had constantly before me, which it seems to me I am forever seeking in my compositions: space and nature.”

Martinů started violin lessons at age 7; he progressed rapidly and began writing little pieces for family occasions. By 15 he was earning rave reviews for his public recitals. Encouraged by his parents, who eyed a concert career for him, he was accepted into the Prague Conservatory in 1906. However, he chafed under the restrictions of school and preferred immersing himself in Prague’s cultural life, regularly attending the theater and concerts and playing in outside orchestras. Awestruck after hearing Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande in 1908, he lost interest in performing and became absorbed by the creative possibilities of composing in a modern style, causing further friction at school. It may have been a relief when in 1910 he was expelled for “incorrigible negligence.” From that point he set his own path in music. He spent the next 10 years working as an orchestral violinist and composing furiously to hone his craft. He finally established his reputation in the Czech musical world with the spectacular success of his 1919 Czech Rhapsody, a cantata for baritone, chorus, orchestra and organ, in honor of the creation of the First Czech Republic.

In 1923, the Czech Ministry of Education awarded Martinů a travel grant to study with Albert Roussel in Paris. He eagerly accepted and thrived in the vibrant atmosphere of what was then the epicenter of the musical avant-garde. He assimilated the new styles he experienced – Stravinsky, jazz, Poulenc, and Ravel – and melded them with his Czech musical heritage. His Paris years were incredibly productive, and his acclaim grew in Europe and America as well as back in Prague, where he periodically returned for visits and performances of his works. But after 1938 he would never see his homeland again. He was blacklisted for two works he composed to protest the Nazi occupation of Czech lands, his Double Concerto (1938) and the cantata The Field Mass (1939). After France fell in 1940 he was no longer safe there, either. In fact, the Gestapo broke into his Paris home to arrest him, unaware that just the day before, he had fled to the south of France.

After months of uncertainty, Martinů secured passage to America via Portugal and settled in New York in 1941. He found it difficult to work at first — he was homesick, depressed by the war, and could not speak much English. Eventually his normal compositional productivity was restored. Recognition by prominent musicians like Serge Koussevitsky, who commissioned him to write his first symphony, brought many successes and helped to establish the next phase of his career. Martinů believed that life in America stimulated his creativity: “My work is developing and getting air – sometimes I can let myself go.” Indeed, he would produce five symphonies in as many years.

Though Martinů desired to return home after the war, a near-fatal fall in 1946 and his unwillingness to live under the communist regime that had assumed power there in 1948 deterred him. And after he became an American citizen in 1952, it was impossible for him to enter any Soviet bloc country. However, a Guggenheim fellowship followed by an offer to teach at the American Academy in Rome allowed him to resettle in Europe (Paris, Nice, Rome, and finally Switzerland) beginning in 1953. Martinů’s productivity continued unabated there, his new works including an opera and four dramatic cantatas. But in 1959 he succumbed to stomach cancer, from which he had suffered for several years. Today, Martinů’s distinctive musical voice lives again in his homeland through the Martinů Foundation, which holds an annual festival of his music in Prague and has sponsored the critical edition of his complete works.

Martinů composed the Czech Rhapsody H307 in the space of about a week in July 1945, just after the war in Europe had ended. The piece was commissioned by the celebrated violin virtuoso Fritz Kreisler and is dedicated to him as well, although Kreisler does not appear to have ever performed it. During its composition, Martinů wrote to a friend that he had surprised himself by choosing the episodic form of the rhapsody, which he had not thought of returning to since his 1919 cantata, and was finding it quite difficult to manage. Nevertheless, Martinů succeeded in embracing the free flow of ideas and unrestrained emotion inherent in the meaning of “rhapsody,” creating a musical kaleidoscope of moods and sound colors.

Warm thoughts of home emerge immediately in the piano introduction, whose ringing chords and octaves evoke the sonic space of the massive bells which had transfixed Martinů since childhood. The violin enters with a sunny yet jaunty melody, whose irregular patterns of accent characterize Martinů’s Czech folk idiom. The melody, supported closely by the piano, rises ever higher, suddenly drops below the piano in register like an echo, and then rushes headlong into the next, more spirited episode. The violin’s new melody is wide-spaced and spiky, and violin and piano begin tossing it back and forth in an exuberant game of call and response. The game becomes more raucous and the texture buzzes with activity — trills, runs, and arpeggios — until a brief piano interlude leads into a playful dance. Again, the piano and violin engage like partners in a rhythmic back-and-forth that culminates in a rising scale passage. After a brief pause the ecstatic atmosphere evaporates and the violin intones a long, heartfelt song, not so sad as contemplative, which is accompanied by rich sustained chords in the piano. Extended melodic repetitions at the close of this episode give the impression that the song does not want to end, but the lyric impulse plays itself out and the spiky melody of earlier returns. Now it accelerates to an even more exciting tempo, and the two partners break into the final episode, another sprightly dance. The piece concludes straightforwardly, in a bright, self-confident flourish. There is no need for a grand swell of emotion. Exuberance has been upstaged by something even more precious: optimism.

Szymon Laks (1901-1983), String Quartet No. 3 “On Polish Folk Themes”, composed 1945

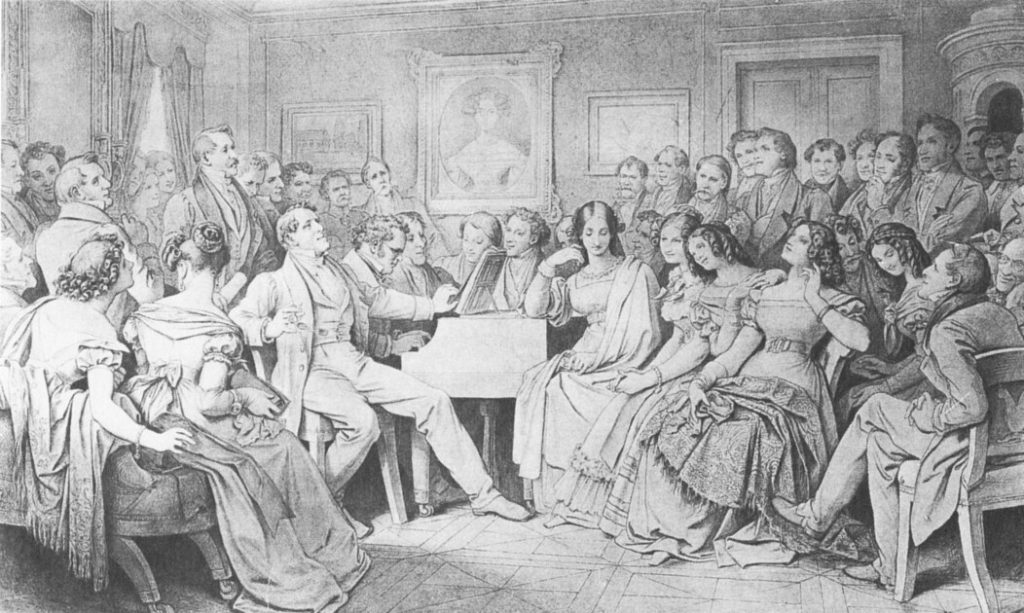

On November 25, 1945, the Sorbonne held a ceremony in Paris to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the death of Polish national hero Adam Mickiewicz, the great poet and political activist who had lived in exile in Paris for 23 years. The program featured a new string quartet with the title, On Polish Folk Themes. Its composer was Szymon Laks, a Polish-born Jew who, like Mickiewicz, had lived for most of his life in Paris. This quartet was the first piece he had written following his liberation in April 1945 after almost three years in Auschwitz-Birkenau. That Laks could create such an eloquent musical statement while still in what was, according to his son, a tremendously fragile state is astounding. But he would soon raise his voice even more powerfully about the atrocities of the camps and about music’s “grotesque entanglement in the hellish enterprise of extermination” in his searing memoir, Music of Another World (1948).

Laks grew up within a family of assimilated Jews in Warsaw. He initially attended university in Vilnius to pursue mathematics, but in 1921 enrolled in the Warsaw Conservatory. His first success was in 1924 with his symphonic poem Farys, which was performed by the Warsaw Philharmonic. In 1925 he left Warsaw for Vienna and worked playing the piano in cafés and movie theatres before moving in 1926 to Paris, where he would remain until his internment. Laks studied composition and conducting at the Paris Conservatory from 1927-29 and then proceeded to integrate himself into the musical life of his new home. One of the first members of the Society of Young Polish Musicians, he won an award for his piece Blues symphonique in the association’s composition competition and worked as its administrator. Over the next decade he wrote numerous orchestral works, concertos, chamber music, piano music, song cycles, and film scores. His reputation as a composer was growing and his music was regularly heard in concerts around the city until the Germans defeated France and occupied Paris in 1940.

The Gestapo arrested Laks in July 1941 and deported him to Auschwitz a year later. He was first assigned to one of the brutal work units, but once his musical knowledge was discovered he was placed in the camp orchestra. Musicians were exempt from hard labor and given better rations so that they could perform their nightmarish rituals: to play twice a day as the rest of the prisoners marched to work and back to their barracks, to give concerts every Sunday for the camp officers and guards, and to perform whenever requested by a member of the SS. Laks had skills that made him invaluable to the system; he became the orchestra’s copyist and arranger, and eventually its conductor. This saved his life. After the Allied liberation, Laks returned to Paris in May 1945 and became a French citizen in 1947. In the 1970s he focused on writing, producing nine collections of essays and French translations of Polish works. He remained in Paris until his death in 1983.

Laks felt compelled to speak disturbing truths about music in the camps and to express his survivor’s guilt in his memoir, Music of Another World. Sentimentality was a pre-war luxury the world could no longer afford. He could see no reason why he survived and others didn’t, and admitted the terrible cost of his privileges. Music, he said, was never “medicine for the sick soul of the prisoners.” It was a “ghastly background that stupefied listeners up to the moment of complete acclimatization and callousness. Music kept up the body of only the musicians, who did not have to go out to hard labor and could eat a little better. Every day I stood eye-to-eye with a horrible two-sided coin: on the one side — hell; on the other — the benefits this hell conferred on Fortune’s darlings, those who had become habituated to it.” Nevertheless, despite his revulsion at those (including himself) who had distorted and perverted it, Laks never gave up on music. After 1945 he continued composing, often drawing on Polish and Jewish folk materials, and was a supporter of music in Polish émigré circles.

Laks must have been overjoyed to at last “speak” his native language through the Polish folk music that he used in his 3rd String Quartet; such music was forbidden in the camps. In a 2005 study, Polish composer/musicologist Antoni Buchner observed that Laks moved far beyond simple quotation, however, achieving multiple layers of meaning. Buchner identified seven melodies from which Laks used segments, rather than presenting the songs intact. The segments function as motifs, recurring elements that permeate the movements in which they appear and constitute a vocabulary of melodic gestures typical of Polish folk style in general. Moreover, these melodies represent seven distinct folkloric regions in Poland, from north to south, allowing all of Poland to resonate. Since folk songs often serve as dance songs, Laks also portrays four Polish dance styles through the rhythmic structure of his settings: oberek, first movement; slow procession, second; mazurek, third; and a rustic dance, fourth. And by referring to the song texts, Buchner traces a unifying narrative arc throughout the piece: the depiction of a young girl, suggesting that she may become a bride; the entrance of a possible suitor; courtship; marriage and celebration. Buchner concluded that Laks “declares allegiance to Poland” through these literal and symbolic means.

I. Allegro quasi presto: The quartet begins with three attention-getting chords, as if to say “ready, set, go!” before launching into the lively oberek, a triple-time dance. Oberek means “to spin,” and the music’s constantly turning figures imitate the whirling movements of the dancers. After the first round of dancing is concluded, the viola introduces the character of the young girl with the sweet and plaintive melody “A little linden tree,” which is taken up by the first violin. The dancers return in the middle section, spinning chaotically in what seems like a dozen different directions. With the return of the three announcing chords, the dance proper resumes. The girl’s melody makes one more shy appearance before the cheerful end of the movement.

II. Poco lento sostenuto: A feeling of sober and worried introspection imbues the opening of this movement; the first melody is from the song “Be careful, little mother, where you send her.”

This song will return with increasing intensity throughout the movement as it alternates with the mysterious-sounding melody introduced by the solo viola: “Through the dense forest walks a soldier.” Faster, more agitated passages serve as transitions between these two songs, but it is the soldier’s melody that will expand passionately and predominate. The closing is simply ominous.

III. Vivace non troppo: This mischievous mazurka brings us back to life. Dancing pizzicatos enliven the texture surrounding the first song, “Perhaps someone will come to us,” which is traditional at weddings. In the middle section, the first and second violins take up their bows to sing a duet of the playful melody, “Let’s make the little kid happy.”

IV. Allegro moderato giusto: The last movement evokes joyful community festivities. It opens with “The Green Grove,” a song sung throughout the Slavic regions to celebrate the arrival of spring. The drone in the cello accompanies its setting as a vigorous rustic stomping dance, with rhythmic activity quickening as the dancers show off their steps. This song is interpolated with the more sentimental “If you love me.” Finally, the dancers return and race to an ecstatic and brilliant finish.

Mieczyslaw Weinberg (1919-1996), Trio Op. 24, composed 1945

Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s story is one that could have been written by Kafka, whose protagonists were forever brutalized by despotic judges who punished them for breaking laws they were forbidden to know about. In January 1948, under orders by Soviet premier Joseph Stalin, Tikhon Khrennikov, head of the Union of Soviet Composers, issued a decree banning works by decadent “formalist” composers. On his list were four pieces by Mieczyslaw Weinberg, a Polish Jew who had been granted asylum in Russia in 1939. Not on the list was Weinberg’s set of Children’s Songs, which were praised for their inspiration in Jewish folk music. In March 1948, Weinberg composed his Sinfonietta No. 1 for orchestra, a piece with obvious influences of Jewish folk music, and submitted it to the Composers’ Union. The work received almost unanimous approval and was performed widely. In 1949, Khrennikov credited Weinberg’s “brilliant, buoyant” music with exemplifying “the bright, free work life of the Jewish people in the Land of Socialism.” In February 1953, Weinberg was arrested, imprisoned, and tortured. The reason? Sinfonietta No. 1, whose folk influences proved he was a Jewish Nationalist out to undermine the Soviet government.

Born in Warsaw to parents who worked in the Yiddish theatre (his mother an actress, his father a violinist and composer), Weinberg claimed “life” was his first music teacher. From the age of 6 he tagged along with his father and listened to performances from the pit. He taught himself to play the piano and by the time he was 10 he was playing shows alongside his father. Already imagining a career as a pianist, he began lessons with a teacher in Warsaw, who recognized his talent and in 1931 enrolled him in the Warsaw Conservatory, where he advanced rapidly. In 1938 the legendary virtuoso Josef Hofmann, on tour in Poland, was so impressed by Weinberg’s playing that he invited him to study at the Curtis Institute of Music and promised to arrange for a U.S. visa. But Hitler’s invasion of Poland in 1939 quashed that plan. Panicked by the immediate danger to their family, Weinberg and his sister Ester fled eastward on foot towards Minsk, along with hundreds of other refugees. When Ester could walk no further and returned home to their parents, Weinberg pressed on through the war zone alone. He never saw his family again, and it would be more than 25 years before he learned that they had been murdered in the Trawniki concentration camp.

Weinberg resumed music studies at the Minsk Conservatory, now as a composer, after he was granted full refugee rights and financial support. In 1941, an invading Nazi army again forced him to flee to Tashkent, in what is now Uzbekistan, where he found work as a tutor and accompanist at the State Opera and Ballet Theatre. Tashkent would be a turning point, personally and professionally. He composed copiously and married Natalia Mikhoels, to whom he dedicated the Piano Trio, Op. 24. He also met Israel Finkelstein, Dmitry Shostakovich’s teaching assistant at the Leningrad Conservatory, and shared with him the score of his first symphony. Impressed, Finkelstein worked with Shostakovich to secure Weinberg a visa to move to Moscow. Weinberg quickly accepted, and from 1943 Moscow would be his home. He was tremendously productive during the remainder of the war, especially in the genres of chamber music and song, and developed a lifelong friendship with Shostakovich.

The reputation Weinberg had built remained intact for a while after the war, until 1946 when anti-Semitic purges and artistic repression became official Soviet policy. As official persecution of Jews intensified and the regime sought to propagandize music, Weinberg was increasingly marginalized — censured, ignored, and banned — until he became a victim himself in 1953. He resumed work with great zeal after his release in April of that year, composing for films and cartoons, raising his Jewish-inflected voice in his concert works, and defending Shostakovich against increased harassment. As the Soviet political environment shifted away from repression, he achieved great prominence as a symphonist in the 1960s. But as he aged, and his old supporters fell from power or died off, Weinberg’s renown dwindled steadily after the 1970s until his death from Crohn’s disease in 1996.

Chicago audiences gained what for many was their first exposure to Weinberg’s music in 2015 when the Lyric Opera presented his opera The Passenger, a harrowing story of Holocaust survivors that he considered the most important work from his extensive catalogue of compositions. Included in his output are 22 symphonies, 17 string quartets, 7 operas, 6 concertos, 3 ballets, 30 sonatas, more than 200 songs, and 60 film scores. Although his music has been mostly neglected outside Russia, a recent stream of new recordings and performances of his works on prominent world stages like Lyric’s have begun to turn the tide.

Shostakovich declared Weinberg “one of the most outstanding composers of the present day,” and at his own personal risk wrote to Soviet officials asking for Weinberg’s release after his imprisonment. Weinberg himself downplayed his peril: “It wasn’t a sword of Damocles, because they hardly locked up any composers — well, except me — and they didn’t shoot any either. I really can’t claim that I have been persecuted.” Nevertheless, he felt it was his obligation to honor and commemorate the victims of war, genocide, and anti-Semitism through works like The Passenger, his Requiem, the symphonic triptych On the Threshold of War, the Piano Trio on tonight’s program, and many others. “Many of my works are related to the theme of war. This, alas, was not my own choice. It was dictated by my fate, by the tragic fate of my relatives. I regard it as my moral duty to write about the war, about the horrors that befell mankind in our century.”

Weinberg composed his Trio for Piano, Violin and Cello, Op. 24, in the early summer of 1945, just after the war ended in Europe. The piece is a companion to Shostakovich’s second Piano Trio, written a year earlier, reflecting the creative dialogue between the two friends, who by this time were meeting almost daily to discuss music and life. Weinberg’s compositional plan seems to draw on his childhood memories of the theatre; the piece unfolds like a series of highly distinctive and evocative scenes. Even within movements the character may shift drastically. The overall impression is of ephemerality: striking and powerful scenes arise suddenly and disappear forever or return in tatters. The trio premiered at the Moscow Conservatoire on January 9, 1947, with the composer at the piano.

I. Prelude and Aria: Larghetto: Majestic chords in the strings announce an angular, strident melody deep in the low register of the piano which runs roughshod over the chords, refusing to march in step with them. The roles reverse and the piano takes up the chordal timekeeping while the strings make a duet of the piano’s melody. When this exchange is concluded, the violin begins with the aria, a frail lament. Eventually its meager strength fails, and the piano takes up the aria, elaborating and expanding it. Suddenly the aria ends and a weird procession takes over, pizzicato in the strings and the dotted rhythms of a funeral march in the piano, and fades into the distance.

II. Toccata: Allegro marcato: An extended scene of conflict and aggression erupts. The piano leads the assault with a relentless, detached and angular melody. The strings attempt to assert themselves, first with an inflected folk-like melody in the violin that is taken up by the cello. The two then join forces against the piano, which answers with a volley of loud repeated chords. Violin and cello take up the piano’s angular melody, and soon all three fight for dominance of the texture. Double stops and trills in the strings and countered by the piano who seizes the opening melody back and hammers it angrily. The movement ends in intense fury, with no winner.

III. Poem: Moderato: The piano again opens, witha lyrical, cadenza-like rhapsody that inexplicably devolves into a brief tango. The tango in turn disintegrates into a string duet, the violin’s pizzicato punctuating the cello’s mournful song before they are joined by the piano. The three instruments then begin a sinister-sounding dance that explodes into a fury of wild trills and massive chords, all lyricism banished. The sardonic tango reappears, ushering in a short chorale before the violin closes the movement with its own cadenza.

IV. Finale: Allegro moderato: The movement begins with an unmoored and meandering melody in the piano; as it winds down, the violin introduces a rapid aggressive theme which transforms into a variation of the opening. A devilish dance performed by violin and piano ensues, which morphs into a folk-like song for cello and piano before the violin interrupts with its aggressive opening theme. A massive fugal section follows, whose angular dissonant theme is stated first by cello, then piano, then violin. This section builds to a long, episodic, and violent climax that evokes the opening Prelude as well as the the grotesque world of the Shostakovich trio. The finale’s opening theme then returns in somewhat faded form, and the chorale from the Poem trails in to draw the movement to an unsettled (and unsettling) close.

Linda Berna