Celestial Bodies, Celestial Music

In this modern age of specialization, we view the sciences of music and astronomy and philosophy as completely separate disciplines. But their roots are surprisingly intertwined, which is perhaps why countless composers and songwriters have looked to the heavens for inspiration.

…Stars with the seasons alter; only he

Who wakeful follows the pricked revolving sky,

Turns concordant with the earth while others sleep;

To him the dawn is punctual; to him

The quarters of the year no empty name…

In 2017, almost a century after Sackville-West wrote her paean to the cycles and processes that regulate the universe independently of human activity, the New York Times began to publish an annual Space and Astronomy Events Calendar. Significant astronomical events that will take place in the coming year — eclipses, meteor showers, solstices, equinoxes — appear in chronological order from January 1 through December 31, and the Times invites its readers to “sync their personal calendars with the solar system.” From the charts of celestial bodies’ movements created by the ancient Babylonians, to the 10th century observatory built by Muslim astronomer Abu Mahmood Khojandi, to the invention of the telescope in 1608, to today’s probe and satellite launches celebrated in the Times’ Space and Astronomy Calendar, our fascination with the heavens and its sun, moon, stars, and planets has continued unabated. After many thousands of years, we are still searching for knowledge and understanding in the vast space of the cosmos.

Connecting music and astronomy

The ancients hoped to glean more from the universe than the precise knowledge of the material world and the forces that control it. They sought metaphysical truths about the nature of existence as well. Enter Pythagoras (c.570-495 BCE), a Greek philosopher who influenced much of Western thought on science, ethics, aesthetics, and mathematics. Known for the Pythagorean theorem, a fundamental of Euclidean geometry (which, despite the name, he did not actually discover), Pythagoras is credited with being the first to propose a connection between music and astronomy, a perception that arose through his belief in the power of numbers to order the world.

Pythagoras began his investigation with acoustics. In an instrument like the lyre, strings of different lengths do not sound the same pitch. Often when two strings are plucked together the combination, which he called the interval, is unpleasant to the ear, but three particular intervals he found to be the most pleasing (consonant), and those combinations he called “perfect.” Comparing the string lengths of these preferred intervals, he saw that they could be represented as ratios of the smallest whole numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4. The perfect octave has a ratio of 2:1 (i.e., the string that sounds the pitch an octave higher is half the length of the string that sounds the lower pitch). The other two perfect intervals were the fifth (i.e. C up to G on the keyboard, ratio of 3:2) and the fourth (i.e. C up to F on the keyboard, ratio of 4:3). The less pleasing and harsh intervals do not possess these perfect ratios.

The harmony of the spheres

For Pythagoras, this was significant: the ratio between string lengths matters, not the lengths themselves. Therefore, the structure of music consists of relationships which can be expressed numerically. Merging the numerical data with perception, Pythagoras then connected human experience to abstract mathematics. What appears to be a subjective judgment (whether an interval sounds good or bad) can be justified by the numbers. And by applying his musical findings to contemplation of the cosmos, Pythagoras developed his doctrine of “the harmony of the spheres.” Sound is produced when objects (like vibrating strings) move the air, so as celestial bodies move across the sky, they must produce sounds relative to their size and speed of revolution.

Upon calculating the distances of the moving bodies from each other, just as he had measured string lengths, Pythagoras concluded that the distances between Earth and the Supreme Heaven, Earth and the Sun, and the Sun and the Supreme Heaven had the same ratios as the perfect musical intervals of octave, fifth, and fourth, so the sounds they make must constitute harmony. Voilà — a metaphysical truth! The same numbers that structure music also structure the cosmos.

Harmonia

The Pythagorean insight that linked music and mathematics would prove both foundational and inspirational for the disciplines of music theory, music perception, and acoustics, generating a continuous stream of mathematically-based ways of thinking about, representing, and analyzing music, from the Middle Ages through the late 20th century. But the notion of the harmony of the spheres has a bit of “The Emperor’s New Clothes” about it. Even in the 4th century B.C.E., questions arose. Why can’t we hear celestial music, which ought to be very loud, considering the size and number of planets and stars in constant vibration? And how exactly could Pythagoras measure planetary distances? There was never a convincing answer to these and other problems. Nevertheless, the concept of a harmony that ordered all things earthly and celestial was evidently so compelling that thinkers of the time brushed aside its difficulties. First among the champions of Pythagoras was Plato, who declared astronomy and music “sister sciences” and introduced the principle of harmonia (Greek for “fitting together”), the mathematical proportions that governed the world of phenomena from the heavens to the human spirit.

Musica mundana, musica humana, musica instrumentalis

Taking up where Plato left off was Anicius Manilius Severinus Boethius (c.480-524 C.E.), the most influential music philosopher of the early Middle Ages, whose early-sixth-century treatise De institutione musica (The Fundamentals of Music) formed the foundation of the field of music theory in the Western world. Boethius defined three kinds of music: musica mundana, cosmic harmony created by the motion of the planets and the rhythm of the seasons; musica humana, the harmony of body and soul; and musica instrumentalis, the harmonies that are produced by singers and instrumentalists. He quoted Plato on musica mundana, specifically Plato’s conclusion that “the soul of the universe was joined together according to musical concords.” He linked musica humana to Pythagoras, stating that the sensual pleasure we take in musical sounds is not a feeling but a “truth” discovered by reason (i.e., that consonance is based on numerical ratios). But musica instrumentalis did not interest him. Music’s purpose for Boethius was not for pleasure, entertainment or creative expression, but rather to train the mind for the study of philosophy. Understanding the numerical basis of harmony would lead to knowledge of the ultimate cosmic organizational principles of number and proportion. Accordingly, Boethius linked four quantitative disciplines together as the essential fields of study for developing high-level thinking. He called this grouping the Quadrivium, and it included arithmetic (number in itself), music (number in proportion), geometry (magnitude), and astronomy (magnitude in motion).

Boethius himself met an unfortunate end, imprisoned and executed on false charges of treason. However, his Fundamentals of Music influenced music teaching for more than a millennium. Throughout the Middle Ages it was regarded as the ultimate authority on the principles of music; with the establishment of universities in the 12th century it became required reading. Preserved for centuries in manuscript form, it was one of the first music books to be printed (Venice, 1492). At Cambridge and Oxford, it remained the standard music theory text until 1856. Medievalist Calvin Bower, modern translator of Fundamentals, called Boethius an exciting teacher whose text was “eloquently assembled to persuade the reader that music not only pervades every sphere of human life, but governs the universe as well.”

Musica Universalis

Meanwhile, the ancient idea of celestial music, a musica universalis, kept percolating among philosophers of both music and science. It found fresh application in the 1619 treatise

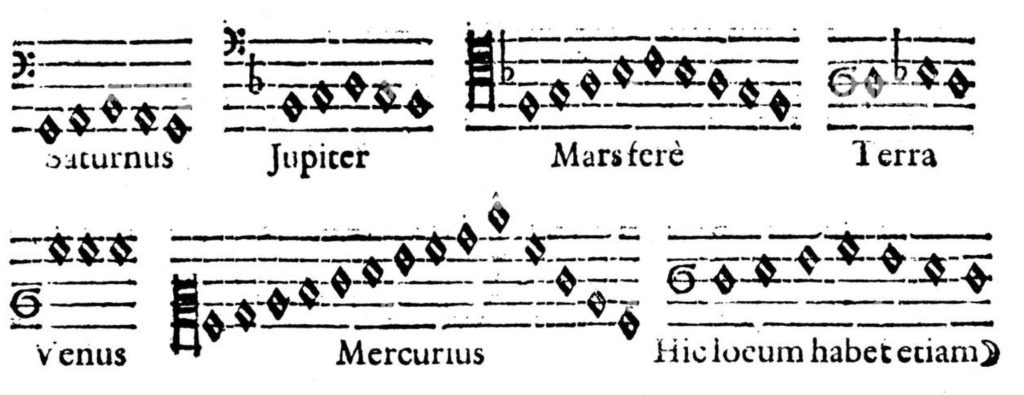

Harmonices mundi (Harmonies of the World) by astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630). Kepler, famous for his three laws of planetary motion still considered valid today, continued Platonism’s project of illustrating the structure of the universe through the intervals of the musical scale. The most important of these laws for music was the third one, which posited that the planets operate within a harmonic system. A planet’s orbital speed is not constant; it accelerates and decelerates depending on how far it is from the sun, and the ratio between these two speeds is the same as the Pythagorean perfect fifth ratio of 3:2. This discovery led to Kepler’s conviction that each planet “sings” a range of pitches corresponding to the range of these two velocities, and that together, the planets express the complete musical scale. Kepler said we cannot hear planetary harmonies from earth because of the lack of air in celestial space, but maintained that they exist even so, and demonstrate the kinship between music and the cosmos.

Kepler was one of the last scientists to advance the idea of musica universalis. Even while validating and applying much of Kepler’s other work in his own research, Isaac Newton in 1683 declared the music of the spheres to be a “myth.” No modern scientific research has given it credence. Yet the idea maintains its grip on the human psyche as a metaphorical concept in art, literature, philosophy, and psychology – so strong, perhaps, is our desire for a unifying explanation that promises to reveal the interconnectedness of all things to each other and to ourselves.

The symbolic repertoire

Art historian Jack Tresidder has written extensively about the importance of symbols in the world’s cultures, noting that “familiar features of the earth are all included in the symbolic repertoire.” The sun and moon are two of the most powerful symbols in human thought, lending themselves to an abundance of meanings. The sun can symbolize creative energy, vitality, and passion; because it brings light out of darkness it can represent knowledge and truth. Hope, new beginnings and eternal renewal are evoked by its emergence each day. Yet its heat can also be a destructive force. We relate the cycles of the moon to planting, the bounty of harvest, fertility, and the rhythms of life. Its many phases and forms suggest transformation and the potential for change. The moon’s nocturnal presence connects it to mystery, magic, fantasy, and dreams, but to delusion and madness as well.

It is no wonder, then, that the ancient instinct to explain everything through music has held its allure, because music itself symbolizes connection. All human cultures do not make the same kind of music, but all human cultures make music. Music partners naturally with song, dance, drama, and ceremonies of all types from religious rites to political events like sit-ins and coronations. Darwin believed that the capacity for musical appreciation connected animals and humans. Psychotherapy, geriatric science, and neuroscience have incorporated music into their practices, while acoustic ecology integrates science, aesthetics, and sociology to study the impact of sound on living creatures. The great anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, who described his own work as “the search for unsuspected harmonies,” declared music “the supreme mystery of the science of man, a mystery that all the various disciplines come up against and which holds the key to their progress.” Music reaches out into the universe in all possible directions.

Linda Berna