George Crumb: Ancient Mysteries and the Universe of Dreams- Program Notes for April 2, 2024

“Maverick”…“Guerilla”…“Shy and somewhat rumpled”…“Soft-spoken and gentle”…“Radical”…“A great communicator”…“Reluctant poet”…“The homebody magician”…“A towering figure”

These are some of the many characterizations of George Crumb, uttered over a long career that earned him an outpouring of critical acclaim and a devoted following that encompassed both performers and audiences. The sound images he created are novel and arresting, inspiring descriptions that demonstrate how strongly his music defies categorization: “eccentric,” “experimental,” “bold,” “sentimental,” “idiosyncratic,” “baffling,” “visionary,” “unearthly,” and “self-indulgent.”

Yet Crumb himself stated, “I’ve never thought of myself as anything but a traditional composer.” So, as the author of a New York Times profile once asked, who is this strange musician?

I came from a place where echoes existed.“

George Crumb

Haunting Sounds That Cross the River

George Henry Crumb Jr. was born on October 24, 1929, in Charleston, West Virginia. His parents were accomplished orchestral musicians, and started his musical training early. Often throughout his life, Crumb acknowledged the imprint on his musical imagination of the rich aural landscape of his home environment. Growing up in a river town in the heart of Appalachia, he absorbed what he would later describe as the “haunting sounds that cross the river at night and bounce back and forth between the hills.” It was why, he stated, he loved to write reverberating sounds in his music: “sounds that ricochet, that go on and on.” His piano parts demand extensive use of the damper pedal; the vibrations of strings, bells, and gongs are made to ring throughout the performance space, mingle, and overlap. To indicate how he wanted something to sound, he frequently wrote quasi lontano (as if from afar) in his scores. Sometimes he has musicians play while walking across the stage or from offstage, thus changing or obscuring the origin of the sound.

Crumb believed that all composers draw on what they’ve lived and heard and that each one naturally inherits their own acoustic from where they grew up. He attended not only to natural echoes but also to a vast inventory of musical and human sounds that permeated his unconscious. Classical music, pop music, folk music, country and church music, singing, mourning, musical saws, mandolins, banjos, hammered dulcimer — all these and more found their way through his ears into his scores. His last work, Kronos-Kryptos for 5 percussionists, calls for 100 sound sources, including gongs, xylophones, marimbas, hammers, cowbells, chimes, a wind machine, metal plates, Tibetan prayer stones, and splashing water. In addition, Crumb saw himself continuing a centuries-long tradition of expanding the expressive range of instruments and voices; he asserted in a 1980 essay titled “Music: Does It Have a Future?” that it is “incumbent on each age to ‘reinvent’ instruments as styles and modes of expression change.” For Crumb, that meant devising what we call extended techniques: asking the pianist to produce sound by directly strumming and plucking the strings, placing objects like a metal chain or a metal chisel on the strings to alter the sound; directing the flutist to sing while blowing into the instrument; amplifying the string quartet and having the players bow on the wrong side of the strings. His singers incorporate glissandi, whispering, shouting, overtones, and ululation into their vocal production.

For Crumb, the diverse and vibrant accumulation of sounds heard in pieces like Vox Balaenae and Black Angels constituted the essential acoustic of his music, the “stamp of West Virginia.”

Music is full of cross-references.“

George Crumb

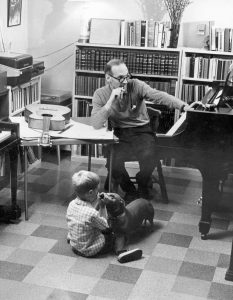

After graduating from Mason College in his hometown, Crumb earned a master’s degree in Composition from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Seeking employment in 1959 after completing his doctorate at the University of Michigan, he accepted a teaching position on the piano faculty of the University of Colorado, Boulder. His colleagues in the piano department encouraged him to continue composing, and it was during his five years in Colorado that he solidified his unique personal style. Following a year spent as composer-in-residence at the Buffalo Center for the Creative and Performing Arts, in 1965 Crumb joined the composition faculty of the Department of Music at the University of Pennsylvania, and he taught there for 30 years.

Night Music

Of the pieces composed during his Colorado years, Crumb considered Night Music I (1963, revised 1976; for soprano, piano/celesta, and two percussionists) an artistic breakthrough, and we can point in this work to several of what music theorist Steven Bruns (a specialist in Crumb’s music) called “fingerprints” of Crumb’s musical identity. These are symbolic and pictorial notation, unusual sounds and descriptive titles that evoke things and experiences from outside the music, and the element of spectacle — all of which can be subsumed under the idea of intertextuality. This concept stems from the conviction that works of art are not closed systems. A piece of music contains a network of meanings associated with the culture, society, and life experiences of the person who composed it. More importantly, that composition inspires other associations in its listeners; the sounds they hear will remind them of other sounds from their own experiences and memories, and they will assign their own meanings to them.

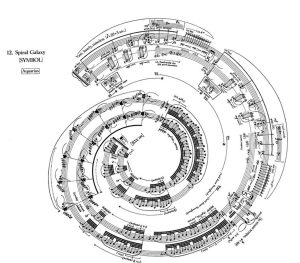

Crumb avoids always notating his music in the conventional five-line staff that is read from left to right and follows a linear organization. His hand-drawn staves are broken into segments that curve and bend around the page. He never used a computer to notate his music, and his calligraphy is so delicate and artistic that his scores have even been exhibited in art museums. In Night Music I, he arranges the instrumental parts of one movement around two red circles, one for the keyboardist and one for the percussionists. The players can start anywhere on their circle (because where is the beginning of a circle?) and proceed in either direction. Rather than confusing them, this is meant to deepen their awareness of the mood and flow of the music by letting them create their own circles and feel the cycle of the moon’s nightly rising reinforce the images in the poem (moon, orange, coins). Other pieces show even more elaborate arrangements. In Makrokosmos I, a set of twelve pieces for amplified piano, three of the movements are in the form of graphic images (a cross, “Crucifixus;” a circle, “The Magic Circle of Infinity;” a spiral, “Spiral Galaxy”). The score of the final movement in the subsequent volume, Makrokosmos II, is a peace sign. In this manner, Crumb expands the network of associations beyond the aural into the realm of the visual to allow the musicians to react more creatively to the music.

Reimagining the Sonic World

Two other intertextual devices bear mentioning: the use of unexpected sounds and descriptive titles to bring even more associations into the experience. Crumb makes the listener reimagine the sonic world of his ensembles. In Night Music I, the natural world enters via bird calls created by a percussionist’s whistling, a tub of water is used to alter the sound of a reverberating gong, and the prepared piano imitates a harp. To the string quartet of Black Angels, he adds crotales (antique cymbals), maracas, and crystal goblets. Vox Balaenae employs whistling and crotales, and the cello imitates a seagull. The title Night Music introduces three other composers and their music into the mix: Mozart (Eine Kleine Nachtmusik), Bartók (who wrote several pieces with the same title), and Mahler (whose 7th Symphony includes two movements titled Nachtmusik I and Nachtmusik II). A fourth, Chopin, appears when we note that each of the seven movements of Crumb’s piece is titled “Notturno” (nocturne). Such a strategy invites the listener to think about how music inspires feelings of night, recalling these other musics, and contemplating Crumb’s relationship to them. The two pieces on tonight’s program share this feature. The three sections of Black Angels are called Departure, Absence, and Return: a reference to Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 81a “Les Adieux,” whose three movements bear the same headings and which he wrote while Vienna was under siege by Napoleon. Ominous implications arise with other titles: “Night of the Electric Insects” and “Lost Bells.” In Vox Balaenae, the sections of the middle movement are called by the names of earth’s geologic epochs, evoking ancient eras so remote and so vast in length that one’s sense of the passage of time vanishes. The final movement’s title, “Sea-Nocturne (…for the end of time),” invokes both Chopin and Messiaen.

Arenas Both Ritual and Theatrical

Finally, the performative aspect of Crumb’s music transports it to the arenas of both ritual and theatre. The musicians must go beyond executing the notes in the score; they expand upon the musical sonorities with gesture, movement, and costume. In Night Music I, the singer’s vocabulary of sound is histrionic, including whispers, shrieks, and half-speech/half-song. At the same time, the pianist rises and reaches deep inside the piano to manipulate the strings, and the percussionist slowly lowers a gong into a tub of water. The ensemble performing Vox Balaenae must wear masks and play under blue stage lighting; they, too, must whisper, whistle, and delicately strike a set of crotales. Crumb asks the quartet of Black Angels to intone a series of numbers in different languages, whisper, and move about the stage to carefully create an ethereal sound by bowing the rims of water-filled crystal goblets. These dream-like spectacles, as a whole, reflect the movement of the musical sounds through time and space and intensify the experience for both performers and audiences.

I think all the music in the world converges at a certain point….Time really is circular and it can intersect any past thing and project future things.“

George Crumb

Quotation, Pastiche, Text, Timbre

Perhaps the most salient feature of Crumb’s penchant for intertextual references is his frequent insertion of other music in his pieces – either direct quotation, as with Schubert’s Death and the Maiden and Saint-Saëns’s Danse macabre in Black Angels, and Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra in Vox Balaenae, or pastiche (imitation), like the renaissance-inspired Sarabande and the Messiaen-like “God Music” in Black Angels. He even employs self-quotation, recalling passages from his earlier works. Stephen Bruns has written at length on Crumb’s extensive linking to Mahler through quotation, pastiche, text, timbre, instrumentation, and formal organization in his music written between 1963 and 1970 (Night Music I; Eleven Echoes of Autumn; Songs, Drones, and Refrains of Death; Night of the Four Moons; Ancient Voices of Children).

Composers have borrowed for centuries — from each other, from past works and styles, and from the songs and dances that were the common property of their cultures. Quotations from the past had previously been a means of establishing a chain of authority, legitimacy, or truth or as an homage to previous eras. The practice takes on special significance in the modern era with musicians such as Mahler, Crumb, Ives, Rochberg, Berio, and Schnittke, to name a few, in light of changing views on time and history. Quotations, especially when fragmented and juxtaposed with the sounds of the now as we hear in Crumb’s music, become a way of reversing the directionality of time, confronting and destabilizing the past, and finding new uses for the materials in our memories. Crumb said that by making a point of contact with the past, he could create an “arch over the centuries.” We are not beholden to the past; it belongs to us and is subject to inquiry and questioning in the present.

Indeed, when interviewed by Edward Strickland for the book American Composers: Dialogues on Contemporary Music, Crumb seemed to view the presence of other musics, in his thinking, not as an intrusion or an influence but as a psychological necessity of the creative process to be worked out in his own scores and presented to his listeners so they could make their own associations. “I think composers are everything they’ve ever experienced, everything they’ve ever read, all the music they’ve ever heard. All these things come together in odd combinations in their psyche, where they choose and make forms from all their memories and imaginings.”

As long as there’s a world around, I guess there’s a chance for any music to make its way.

George Crumb

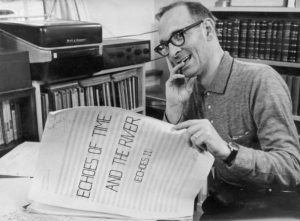

Echoes of Time and the River

Over the course of his long life, George Crumb earned wide recognition, including the 1968 Pulitzer Prize in Music for his orchestral work Echoes of Time and the River; a Grammy Award in 2001 (Best Contemporary Classical Composition) for Star-Child; and the 1998 Cannes Classical Award for Best CD of Living Composer, to name a few. By the early 1980s, Crumb had become one of the few living composers to have all the major American orchestras (New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Cleveland, Boston, and Los Angeles) perform his music. As noted in the announcement that he had been named Musical America’s 2004 Composer of the Year, he enjoyed a wide international following of music lovers who eagerly awaited each of his new works and packed the concert halls to hear them. Many heartfelt tributes marked his death in 2022 at the age of 92, none more touching or apt than that of his Penn colleague Jay Reise: “He had a manner that was uplifting; there was a serenity and quiet to his demeanor that without raising the volume a decibel could become passionate. And he was always passionate about music….He wrote, ‘Music can never cease evolving; it will continually reinvent the world in its own terms.’ George Crumb stimulated us to broaden and expand our musical horizons. If music does have a bright future, his will be a strong influence on how that music reinvents itself.” Crumb, by crafting new and remarkable worlds of sound out of what he heard, saw, felt, thought, and dreamed, expanded our ideas of what might be possible. He shared his vision of music’s power to speak to us of who we are, where we have been, and where we might yet go.

Vox Balaenae (1971)

In 2011, the Journal of the American Musicological Society published a collection of five interrelated essays devoted to the theme of ecomusicology, a relatively recent branch of inquiry that examines music’s relation to the natural world — how it can be inspired by the sounds of our natural environment as well as open our eyes not only to its grandeur and beauty (Messian’s Catalogue d’oiseaux, Grofe’s Grand Canyon Suite) but also to its degradation (Peter Maxwell Davies’ Farewell to Stromness, Matthew Burtner’s Glacier Music). Popular music, of course, had already had its eyes on the latter for about 50 years, with such songs as Joni Mitchell’s Big Yellow Taxi, Marvin Gaye’s Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology), Randy Newman’s Burn On, and John Prine’s Paradise. Not coincidentally, perhaps, the last three of these songs date from the same year as Vox Balaenae, and Big Yellow Taxi from the year before.

Revealing his belief that music is in and of the world, not an aesthetic object apart from it, Crumb allowed in a 1992 interview that Vox Balaenae might be a “statement” on environmental issues: “I think of music as being so intimately connected with nature to start with.” In 1980, he asserted in his essay “Does Music Have a Future?” that “the rhythms of nature — large and small, the sounds of wind and water, the sounds of birds and insects — must inevitably find their analogues in music.”

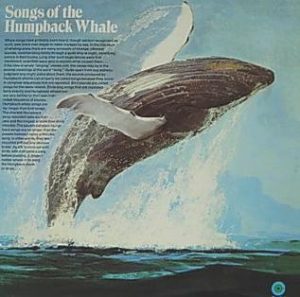

Crumb had first heard a tape of humpback whales singing in 1969. Apparently, he was struck by their non-human musicality, observing in the 1980 essay that whale song was already a “highly developed artistic product: one hears phrase structure, climax and anticlimax, and even a sense of large-scale musical form!” He placed the ancient animals’ expression front and center in this piece, calling it “nature dehumanized,” having the players wear masks and perform under blue lighting to “efface a sense of human projection” and “symbolize the powerful impersonal forces of nature.” Crumb was much more explicit about his distress at the state of the environment in his only other nature-based work, An Idyll for the Misbegotten (1985), writing, “Mankind has become ever more ‘illegitimate’ in the natural world of the plants and animals. The ancient sense of brotherhood with all life forms…has gradually and relentlessly eroded, and consequently, we find ourselves monarchs of a dying world.”

Crumb takes us back to the beginning of time with his dream of primordial music-making — song — in the opening movement of Vox Balaenae. It is as if the lyric impulse existed in the world long before humans gave it voice; we are neither its oldest nor its best practitioners. The variations of the second movement take place in Sea-Time, which is so long that humans have little place in it and yet so rich with the transformations of life and organic matter. Time, in the closing Sea-Nocturne, gently fades out in a way we can only imagine — or possibly moves beyond what we are able to perceive and is still resounding.

Black Angels (1970)

Johnnie Burn, Academy Award winner for cinematic sound design in 2023’s The Zone of Interest, recently recounted his process to recreate the sounds of Auschwitz as heard from outside the fence. Because the camp is never seen in the film, sound carries an enormous share of the weight of storytelling. Burn explained, “Pain exists in the real world, and to present that is powerful. I believe that humans seek more truth in what they hear than what they see. You believe it more because of that primal connection; sound is something you react to as opposed to something you process. You can shut your eyes, but you can’t shut your ears.” Crumb shied away from identifying political messages in his or any music, declaring, “I’m not sure that music can carry the weight of propaganda” in 1992. He preferred to characterize Black Angels rather more generally as “a parable on our troubled contemporary world.” But the sounds of pain are palpable in the work nevertheless. David Bowie, who counted the Kronos Quartet’s rendition of Black Angels as one of his top 25 recordings of all time, wrote that it was “a study in spiritual annihilation…it scared the bejabbers out of me.”

In 1970, Crumb was also writing Ancient Voices of Children, settings of five poems by the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca (1898-1936), with instrumental interludes for soprano, boy soprano, oboe, mandolin, harp, amplified piano/toy piano, and percussion. Crumb has been more willing to expand on this work and its connection to Vietnam, stating in a 2020 interview on WOSU public radio: “We were involved in the war in Asia, you know. A lot of children lost their lives in that war. And I think that was sort of in the air, the sense that, why are we over there, and what is happening?… I’m talking about the Vietnam War that we were involved in. And that was hanging over everybody’s thoughts. I think that was part of maybe the reaction when they heard my setting of these texts.”

The images in Lorca’s poetry, both spiritual and dark, inspired Crumb throughout his life; between 1963 and 2012, he produced 12 major works on Lorca texts. Lorca finds his way into Black Angels, too. Stephen Bruns describes the inscription Crumb made in his sketches for the piece, two lines from Lorca’s ballad Reyerta (Brawl): “Y ángeles negros volaban/par el aire del poniente” (And black angels were flying through the air of the setting sun).

If Vox Balaenae is a dream, Black Angels is a nightmare. We are right to hear Crumb’s harrowing sound images as a metaphor for the horrors of war and to perceive the association between the work and Vietnam, the tempore belli (time of war) raging in 1970, which Crumb inscribed at the top of his score. We cannot shut our ears to the brutality and the malevolence of the Devil-Music, to the sorrow that infuses its threnody, the song of mourning for the dead, nor to the ethereal and almost unreachable peace we yearn for in the God-Music.

Further reading:

A Conversation with George Crumb (YouTube)

Crumb, the Tone Poet (New York Times)

George Crumb, Eclectic Composer Who Searched for Sounds, Dies at 92 (New York Times)

The George Crumb official website

A Conversation with George Crumb (George Crumb Festival, Boulder, October 1992)