George Crumb’s Black Angels: Music For Our Time

We often imagine music as reflecting the time in which it was composed. But the same music can also be a timeless language, one that crosses the boundaries of time between the past, present and future. George Crumb’s Black Angels is one such piece that, while firmly rooted in its time of origin, reflects global tensions and horrors of war that are just as meaningful today.

Crumb completed Black Angels in March 1970, during the height of the Vietnam War, which looms throughout in its sounds and structure. Crumb wrote the Latin phrase in tempore belli, in time of war, into the score. With numerological implications, obsessive symmetries, palindromes, and quotations throughout, the piece is full of subtexts and hidden meanings. Through these and many other compositional devices, Crumb creates a unique sound world reflecting the complexities and tragedy of death in times of war.

The Devil is in the Details

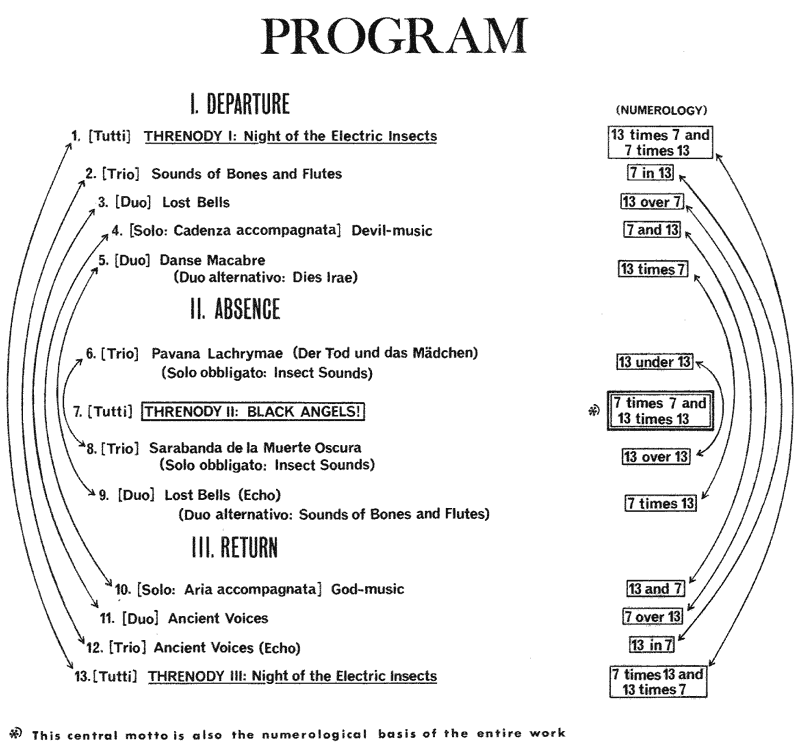

George Crumb’s Black Angels is divided into three main sections, as shown in the diagram below:

Each section represents Crumb’s overarching themes. The sections contrast one another through religious subtexts presented by textural and dynamic extremes, contrasting instrumental ranges, and juxtapositions between tonal and atonal musical sections. Further, many of the explicitly tonal sections of the work are quotations, which Crumb uses to connect the past to the present. A great example of a quotation explicit in its implications with death is his quotation of the second movement of Schubert’s String Quartet in D Minor (D.810).

The slow movement of the “Death and the Maiden” Quartet— by its very nickname, has romantic-era associations with death. This section highlights the theme that runs through much of the quartet: Vietnam-era exhaustion camouflaged as a stereotyped nineteenth-century artist’s worldview.

Blair Johnston, Journal of the Society for Music Theory

The deeper you look into the piece, the further down the rabbit hole you can fall. Crumb also quotes the “Dies Irae,” an ancient Gregorian chant often associated with solemnity and death as it was recited at the Mass for the Dead in the Middle Ages. This haunting sequence appears in several places throughout the piece. The names of the sections are also important to discuss as the Threnody movements, in particular, give further subtext to the throughline of the horrors of war.

In addition to quotation, Crumb also utilizes symmetry and numerology to tie the piece together. Black Angels is brimming with an almost obsessive symmetry. The three Threnody movements mark the beginning, middle, and end of the piece. “Devil Music” and “God Music” are symmetrical in their position within the piece while being opposite in terms of religious meaning. Symmetry in the number of instruments is also featured in each movement, ultimately creating a palindrome that spans the entire piece.

Crumb writes “tutti,” “trio,” “duo,” or “solo” at the beginning of each movement (on the diagram and on the score), making clear the sequence [4, 3, 2, 1, 2, 3, 4, 3, 2, 1, 2, 3, 4], which is symmetrical as a whole and also internally.

Blair Johnston, Journal of the Society for Music Theory

Crumb also presents subtexts of war and fate through the use of numerology. The numbers thirteen and seven, connected historically to fate and destiny, are used throughout the piece. The number 7 is potent in its religious meaning, representing the sabbath in liturgical numerology. In the book of Genesis, God rested on the seventh day, and thus, the number is often associated with rest and connection with God. Juxtaposing the numerology of 7, the number 13 is often associated with Evil; however, the number 3 can also signify Good (The Holy Trinity). Adding to the complexity, the number 3 can also be associated with Evil, as the omnipresent use of the tritone by Crumb, containing 3 whole steps and 6 half steps, was a musical interval so dissonant that in the Middle Ages, it was banned by the church and considered the devil’s interval. Crumb’s oppositional use of these numbers creates an unsettling contradiction that leaves the audience wondering whether there is such a thing as truly Good or truly Evil.

In various spots, melodies consist of 13 notes or are 13 measures long. Within a melody, musicians may be asked to repeat a note 3, 7, or 13 times, and sometimes Crumb instructs the musicians to repeat passages 3, 7, or 13 times. Crumb often described the magical relationship between fateful numbers, and many of the sections include time signatures that indicate 13/7 or 7/13, infusing every musical element with fate. Such heavy subtexts add to the religious overtones of Black Angels, elevating the message of the global and societal consequences of war.

Otherworldly Sounds

Crumb’s sound worlds are unlike any other that came before him. The uneasy harmonics and fragmented melodies keep the audience in a consistent state of suspense and wonder. Black Angels is particularly potent in terms of timbre and texture. Throughout the piece, Crumb utilizes moments of calm, such as in God Music, to create momentary reprieves from the aggressive dissonances of sections such as Threnody I, II, and III. However, these moments are emphasized by a lingering dread and uneasiness presented by the motifs of electric bugs in the string instruments’ highest ranges. Above tension-filled harmonies, a melody may rise out of the voice of the quartet to remind us of music’s omnipotence in presenting us with complex human emotions. In God Music, Crumb weaves together layers of harmonics with a haunting melody from the cello that feels as if it is being sung rather than played by a string instrument. The effect takes us deeper into Crumb’s sound world, showcasing the horrors of war while also introspectively observing the depth of the human spirit and its capacity for hope.

Beyond the Score

Great composers have a special gift, allowing us to receive their inner thoughts through visceral sounds rather than words. With current rising global tensions and active war zones in Europe and the Middle East, it seems that Crumb’s original message reflecting the horrors of the Vietnam War continues to resonate more powerfully than ever. As it courses through its extreme range, extended techniques, and eerie melodies, Black Angels reminds us of music’s timelessness. We hear Crumb’s electric insects on today’s battlefields while the harsh beat of the tam-tam evokes bombs dropping from the heavens. The screams of innocent lives are heard in the extreme range of the string quartet, pushed to its absolute technical limits. Crumb’s message is clear: war is a devastating tragedy, one that pushes humanity to its limits both in empathy and in action. Black Angels, written during wartime in 1970, is, unfortunately, equally relevant in 2024. If we listen closely, we may hear not only music but also new ways of understanding each other.

Black Angels will be performed at Guarneri Hall on April 2, 2024, at 6:30 PM, on a program entitled George Crumb: Ancient Mysteries and the Universe of Dreams.