George Gershwin and Rhapsody in Blue: An Experiment in Modern Music

Rhapsody in Blue is the defining Jazz Age masterpiece that made George Gershwin (1898-1937) a household name in American music. Rhapsody in Blue was written by Gershwin in 1924, just as the Roaring Twenties were beginning to truly “roar.” The work has come to be widely regarded as a musical portrait of New York City at its most welcoming. The Manhattan of Rhapsody in Blue is unfettered by class wars, urban blight, political corruption and racial tension. Rather, the piece teems with the productive energy of commerce and a sense of booming prosperity. Rhapsody in Blue evokes an unbridled optimism that seems to represent a mythical utopia that many New Yorkers have always wanted their city to be. Gershwin himself described his vision for the work as “…a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness.” Gershwin’s ability to write guilelessly sweet, earnest, and elegant music without becoming saccharine is a part of his uniquely American genius. Rhapsody in Blue’s memorable and instantly recognizable tunes and brilliant transitions have held up over time, and it is hard to imagine a more widely beloved piece of music in any era.

The King of Jazz

The commission for Rhapsody in Blue came from early jazz advocate Paul Whiteman (1890-1967), one of the best-known band leaders of the Jazz Age of the 1920s. Whiteman started out as a symphonic violist in the Denver and San Francisco orchestras before forming the Paul Whiteman Orchestra for the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco in 1918. In 1920, Whiteman moved the ensemble to New York, where they immediately became a hit with popular recordings of jazz-inspired dance music. Whiteman was so successful that by 1923-24, he had come to be called the “King of Jazz.” The Paul Whiteman Orchestra’s manicured musical arrangements drew criticism from purists who argued that they lacked the improvisational element of true jazz. Still, Whiteman’s musical leadership and the top-flight performers he hired earned him the respect of some of the best musicians of his era, including Duke Ellington (1899-1974). The polished sound of the Paul Whiteman Orchestra reflected both Whiteman’s disciplined training and his knack for hiring musicians of extraordinary talents. Clarinetist Ross Gorman (c1890-1953) and pianist and arranger Ferde Grofé (1892-1972) were both long-time Whiteman orchestra members. Each of them would come to play a defining role in the legacy of Rhapsody in Blue.

Experiments in Modern Concert Programming

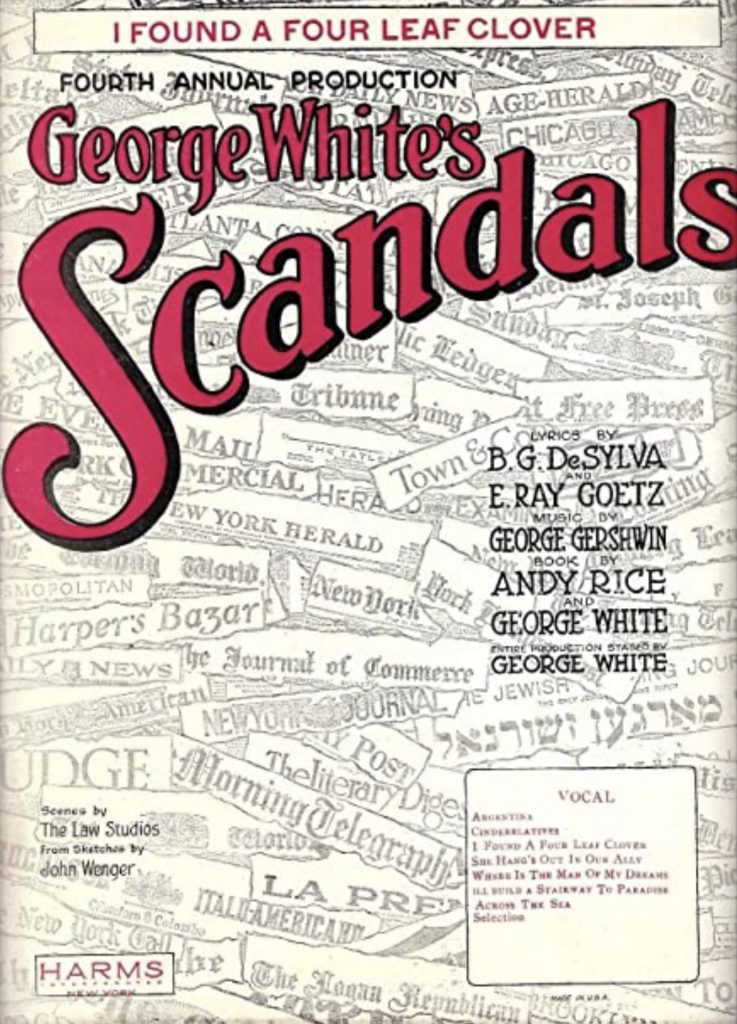

In the early 1920s, jazz was still evolving from its origins in the African American community of New Orleans. Its embrace by musicians like Paul Whiteman and George Gershwin contributed much to its later acceptance by a wider audience. Whiteman and Gershwin first worked together on George White’s Scandals of 1922, a light-hearted musical revue modeled on the famed Ziegfield Follies. Gershwin’s experimental one-act opera Blue Monday was to be included in the revue but flopped on opening night. Blue Monday was immediately withdrawn from subsequent Scandals of 1922 performances, but Whiteman liked the work and admired the young Gershwin’s abilities.

Eva Gauthier

Jazz also benefited greatly from the advocacy and early experimental programming of artists like Canadian singer Eva Gauthier (1885-1958), a well-respected, classically trained concert singer with a background in opera. In the fall of 1923, Gauthier presented an innovative classical-jazz concert at Manhattan’s Aeolian Hall that raised eyebrows. The event, entitled “A Recital of Ancient and Modern Music for Voice,” included music of Bellini, Perucchini, Purcell, Bartok, Hindemith and Schoenberg alongside songs by Jerome Kern and Irving Berlin. The program also included three songs by George Gershwin with the composer himself at the piano. It was the first presentation of Gershwin’s music as concert pieces.

This daring juxtaposition of art music and Broadway song from a singer of real talent and renown created controversy. The recital was a success with the public but received mixed reviews in the press; the notion of programming Broadway songs in the context of art music inspired both passionate approval and criticism. Seizing on the controversy, Paul Whiteman planned an event that was even more ambitious than Gauthier’s—a concert called “An Experiment in Modern Music“ to be presented at the Aeolian Hall in February 1924. Whiteman asked Gershwin to write a “concerto-like” piece for piano and orchestra to be played among 25 other works on the program. This would have been unlike anything the young composer had written before. With the concert just weeks away, Gershwin declined, citing a lack of time to give the work adequate attention. Rhapsody in Blue might never have been written if not for another twist of fate.

You Can’t Trust Everything You Read in The Papers

As the story goes, late in the evening of January 3rd, 1924, George Gershwin was playing billiards with the lyricist Buddy De Sylva (1895-1950). Gershwin’s brother, lyricist Ira Gershwin (1896-1983) sat nearby reading a New York Tribune article entitled “What is American Music”? The article claimed that George Gershwin was working on a “jazz concerto” for the upcoming Whiteman concert. George was bewildered as he knew that no such work was underway! The next morning, he phoned Whiteman, who convinced Gershwin to come through with the “jazz concerto” lest a competitor steal the concept. The concert was by then only five weeks away and Gershwin set to work quickly on a piece he called American Rhapsody. The title Rhapsody in Blue is said to have come later, inspired by titles James McNeil Whistler had given to his paintings: Nocturne in Black and Gold, and Arrangement in Gray and Black.

A Special Arrangement

Gershwin lacked the experience to score his piece for a group as large as Whiteman’s orchestra. He delivered Rhapsody in Blue to Whiteman as a two-piano version with some incomplete scoring indications. Whiteman turned to his brilliant pianist and arranger Ferde Grofé to arrange Gershwin’s manuscript for the Paul Whiteman Orchestra. Grofé is an important unsung hero of the history of the work. His masterful handling of Gershwin’s material was critical to the spectacular success of Rhapsody in Blue. Another such unsung hero is clarinetist Ross Gorman, who during rehearsal poked fun at Gershwin by turning the first measure of the piece into a humorous glissando. Gershwin loved the embellishment and asked Gorman to do the same at the concert, with as much of a wail as possible. Grofé’s orchestration and Gorman’s glissando would become forever identified with Rhapsody in Blue.

Ferde Grofe

Ross Gorman

Grofé’s original orchestration of Rhapsody in Blue utilized the full 23-player complement of the Paul Whiteman Band. Grofé would go on to make at least three later arrangements of Rhapsody in Blue, including one for full orchestra in 1942 that has become the most often-played version.

A New Shade of Blue

Another master arranger, Cliff Colnot, has now created an arrangement of Rhapsody in Blue for small orchestra. Colnot’s range of experience as a veteran conductor of serious concert repertoire, and as an arranger with a deep interest in and experience with jazz, aligns with the backgrounds of the stars of the past like Paul Whiteman and Ferde Grofé. Thus, Colnot is extraordinarily well suited to the task of arranging Gershwin’s music in our time. The Colnot arrangement of Rhapsody in Blue is scored for flute, clarinet, horn, trumpet, trombone, piano, percussion, and strings. PDFs of the score and parts are available on the Guarneri Hall website, along with Colnot’s arrangements of a number of other works. These arrangements create access to musical masterpieces for performers and audiences alike, making them an invaluable resource for music education programs, smaller ensembles, and venues with limited space.

The lead image depicts a birthday party honoring Maurice Ravel, New York City, 2928. From left: Oscar Fried, Eva Gauthier, Ravel, Manoah Leide-Tedesco, and George Gershwin. By Wide World Photos, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.