Orion Weiss Recital Program Notes

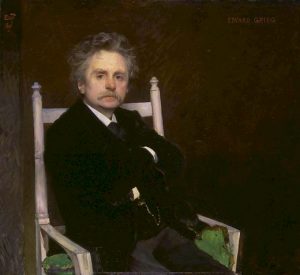

Birth of a Norwegian Icon

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907), Selected Lyric Pieces

At Leipzig, Grieg studied piano under Ignaz Moscheles. He would make his debut as a concert pianist in Karlshamn, Sweden, in 1861. Grieg continued to concertize around the world during his life, becoming friends with composers like Tchaikovsky and Liszt. Liszt gave Grieg suggestions on how to improve his piano concerto, a work that Liszt loved very much.

The piano was always central to the life and work of Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg (1843-1907). His mother, a music teacher, first taught Grieg how to play piano at the age of six. Grieg studied piano at several different schools. It wasn’t long before the Norwegian violinist, Ole Bull, a friend of the Grieg family, noticed young Edvard’s talent and strongly suggested he be sent to Leipzig Conservatory. Which he was.

Grieg’s Solo Piano Music at its Best

Grieg’s piano concerto is one of the best-loved works in the repertoire. Grieg’s solo music doesn’t seem to be nearly as well-known, although once people hear it, they fall in love with it as well. The Lyric Pieces are perfect examples of Grieg’s solo piano music at its best.

Grieg’s Lyric Pieces were composed over more than 30 years, from 1867 to1901. A few of these miniatures, like Wedding Day at Troldhaugen, To Spring, and March of the Trolls have become popular and beloved in recitals, but the less-performed of the Lyric Pieces deserve love and respect, too.

These bite-sized piano morsels come both savory and sweet. Grieg is the master of shifting moods, and the Lyric Pieces are a buffet of multitudinous emotions. Grieg delivers delicious sadness and the painful joy of nostalgia. These are works to be savored, whenever the opportunity might arise.

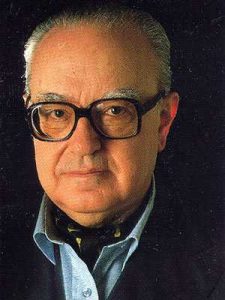

A Precocious American

Samuel Barber (1910-1981), Piano Sonata Op. 26

Samuel Barber (1910-1981) is another composer who began studying piano at the age of six. When he was a mere 14, he entered the young artists program at the Curtis Institute of Music. Barber would go on to have a distinguished career as one of America’s greatest composers. His magnum opus is probably the melancholic and elegiac Adagio for Strings.

Barber was composing at a time when avant-garde techniques like serialism were dominating the classical world. Barber was essentially a romantic composer, but he wasn’t afraid to go avant-garde on occasion. Such was the case with Barber’s Piano Sonata, in which he demonstrated that Americans can do serialism as well as any of the 2nd Viennese composers.

Razzle-Dazzle Star Power

Barber’s Piano Sonata, composed in 1949, was a cause célèbre. First of all, it was commissioned by the two greatest living Broadway composers, Irving Berlin and Richard Rodgers, and Vladimir Horowitz gave the sonata its premiere. This was some major postwar star power.

Since Barber wrote the sonata with Horowitz in mind, he included lots of virtuoso razzle-dazzle. Horowitz’s show-stopping performance was a great success, and he would continue to champion the sonata for years to come, even as other pianists took up its cause as well. Barber’s Piano Sonata is now, deservedly, a standard part of the piano recital repertoire.

A Formidable Reputation

Serge Rachmaninoff (1873-1943), Variations on a Theme of Corelli

By 1931, the year he composed the Variations on a Theme of Corelli, Serge Rachmaninoff had established himself not only as a formidable concert pianist but also as a composer who could stay true to his vision while writing music that the masses would love. One of Rachmaninoff’s favorite personal memories was performing as soloist for his own Piano Concerto No. 3 with Gustav Mahler conducting the New York Philharmonic. A special moment, indeed.

But there were bad memories, too. Rachmaninoff went into a three-year depression after the disastrous premiere of his Symphony No. 1. He eventually emerged and resumed his life of concertizing and composition. Another personal hardship occurred when Rachmaninoff was forced to flee his beloved Russia to escape the violence of the Bolshevik Revolution. He would eventually settle in the United States, where he lived his final years as one of the most revered figures in music.

A Well-Earned Holiday

Rachmaninoff was inspired to write Variations on a Theme of Corelli while on holiday in Switzerland. The Corelli Variations are actually variations on the ancient La Folia theme, which Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) quoted in one of his Concerti Grossi and which found its way into countless other Renaissance and Baroque works. Rachmaninoff dedicated the Corelli Variations to his friend, violinist Fritz Kreisler.

Rachmaninoff’s sly and brilliant variations command the listener’s attention. Rather than his typical heart-on-the-sleeve emotionalism, here Rachmaninoff displays a more restrained elegance. But this is Rachmaninoff, so there are still occasional explosions of romanticism. At times, these variations sound like a prototype for Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. And that’s a good thing.

Introducing Argentinian Forms to Classical Music

Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983), Piano Sonata No. 1, Op. 22

Alberto Ginastera introduced a wide variety of Argentinian dances, rhythms, and forms to classical music. Ginastera was already an accomplished young professor of music when he moved to the United States to study composition with Aaron Copland from 1945 to 1947.

In 1952, the Carnegie Institute and the Pennsylvania College for Women commissioned Ginastera to compose a piano sonata for the Pittsburgh International Contemporary Music Festival. The composer gave the Piano Sonata No. 1 its premiere on November 29, 1952.

Subjective Nationalism

Ginastera considered his artistic periods divided into three: “Objective Nationalism” (1934–1948), “Subjective Nationalism” (1948–1958) and “Neo-Expressionism” (1958–1983). The Piano Sonata No. 1 comes from Ginastera’s Subjective Nationalism period. At that time he was still using Argentinian folk elements in his music, but his works were becoming more abstract than folkloric or pictorial.

Polytonality and Twelve-tone Techniques

Much of Ginastera’s music derives its formidable energy from the same primitivism that Stravinsky unleashed with “The Rite of Spring.” Ginastera uses polytonality and twelve-tone techniques to give his Piano Sonata No. 1 a similar barbaric vitality. There are wonderful flashings of color among the dense rhythms, like glimpses of some beautiful tropical bird in a lush, green jungle. Ginastera’s Piano Sonata is full of creativity and imagination. It deserves a good listen.

Orion Weiss at 6:30 p.m. October 17 at Guarneri Hall, 11 E Adams St Ste 350A, Chicago. $10-$40. 847-780-6720 or guarnerihall.org.