Program Notes for Proust’s Salon: Tracing the Spiral of Time

Guarneri Hall’s event Proust’s Salon: Tracing the Spiral of Time celebrates four figures, three musical and one literary, for whom the salon was an empowering space. Marcel Proust, Gabriel Fauré, Charles Koechlin and Florent Schmitt all frequented the Paris salons of the late 19th and early 20th-centuries. Moreover, they all regarded the salon as an intimate means to transport composers and listeners to a timeless place of reflection and detachment, where past and present intermingle. Our program explores this deeply personal notion of time through a selection of music that might easily have been heard at one of these salon events favored by Proust and his circle.

The Age of Modern Invention

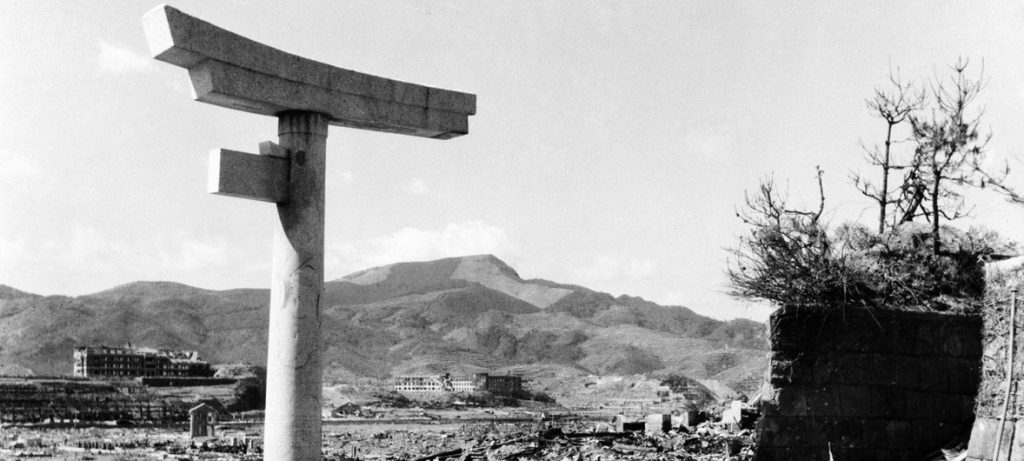

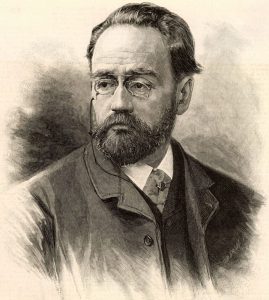

Anxiety and stress spurred by the intrusion of the commercial, political, and technological into our private space and time – these are facts of American life in 2025. We struggle to protect our peace of mind from the relentless onslaught of “fake news,” ideological extremism, artificial intelligence, cyberscams, aggressive consumerism, and the pressure to maintain constant on-line availability. But the French faced very similar problems around the turn of the 20th century. Paris, too, found its way of life upended by drastic social and scientific advances, starting around 1880 and continuing until World War I, that redefined notions of space and time: electricity and artificial illumination, the cinema, the elevator, the telephone, underground rapid transit, the automobile, the airplane. At the same time, an expanded sensationalist press inflamed political strife – republicans against royalists, anti-Semites against Dreyfusards, advocates of centralized government against defenders of local autonomy. “Modern society is racked without end by a nervous irritability. We are sick and tired of progress, industry, and science,” Émile Zola complained in 1896.

However, the invention that did the most to recalibrate time and space, argued historian Stephen Kern in his groundbreaking study The Culture of Time and Space 1880-1918, was instantaneous communication via wireless telegraph, which eradicated the geographical and time differences between places and enabled the creation of standardized global time. The adoption of World Standard Time in 1884, Kern explained, offered political, economic, and legal advantages; a coordinated time system made commercial, governmental, and social transactions uniform and facilitated scheduling regardless of location. France had the most chaotic time situation in Europe, and only gradually accepted universal time, adjusting local practices accordingly. Some regions had four time zones, and each city had its own local time taken from solar readings. The rail system used Paris time, which was about 9 minutes ahead of Greenwich; yet the railroad station clocks were 5 minutes ahead of the ones on the tracks to give passengers extra time to board the trains. In 1891 the French declared Paris time the law for the entire country and finally reconciled its official time with Greenwich in 1911. Regimentation became universal and punctuality a necessity, accompanied by anxiety over being on time. As Kern noted, “Whatever charm local time might once have had, the world was fated to wake up with buzzers and bells triggered by impulses that traveled around the world with the speed of light.”

Bergson, Proust, and the Concept of Time

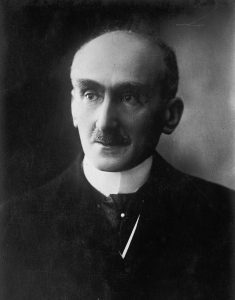

During this era, concepts of a fluid and private psychological time arose in the fields of philosophy, sociology, psychology, and the arts, to counter the regulated pace and external controls imposed by universal public time. French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941) is widely considered one of the most influential thinkers on the nature of time, consciousness, and memory. In his 1889 essay “The Idea of Duration,” Bergson distinguishes between quantity and quality. Counting or measuring temporal units confuses time with space, he avers. Space and dimension enable us to quantify, to differentiate one thing from another. But the perception of quality is what enables us to identify the distinct things to be counted. Therefore, qualities, not measurable dimensions, characterize reality. The first thing the mind does is to perceive qualities; only then can it proceed to quantify. The quality of experienced time, says Bergson, is ever-changing, so it cannot be quantified. “It is a becoming that endures, a change that is substance itself.” The idea of time as synthesized experience, which Bergson calls durée (duration), follows from this conclusion. “Durée is the form which the succession of our conscious states assumes…when our ego refrains from separating its present state from its former states. In recalling these states, it does not set them alongside its actual state as one point alongside another, but forms both the past and the present into an organic whole, as happens when we recall the notes of a tune melting into one another.” Duration is always in a state of “being done,” and “binds the past to the present by this very process of connection.”

French novelist Marcel Proust (1871-1922) also treated time as inner reality; Bergson and Proust were in fact friends and admirers of each other’s work. In his epic In Search of Lost Time (1909-22), Proust rejected chronology in favor of a non-linear spiral of reactions, reflections, digressions, and memories. Time shifts constantly as the narrator’s consciousness wanders among different locales and moments in his life. Proust used the act of listening to a musical performance in one of the salons his narrator regularly attended as a device to spark interior reflection. “The violin had risen to a series of high notes on which it lingered as though waiting for something… And before Swann had time to understand, all his memories of the time when Odette was in love with him, which he had managed until now to keep out of sight in the deepest part of himself, had awoken and flown swiftly back up to sing madly to him… He now recovered everything which had fixed forever the specific, volatile essence of that lost happiness….” (Swann’s Way: In Search of Lost Time, Vol. 1)

That Bergson and Proust illustrated the circularity of time with musical examples is significant. It reflects the elevated position of instrumental music in the late 19th century; the limitless ability of sound to suggest, unencumbered by objective references to the external world, made it unique and prized among the arts. But more importantly, they both exploit similarities between musical perception and time perception. Music perception is a Bergsonian synthesis: it relies on understanding constantly changing, continuous gestures as phrases, melodies, and sections, which can’t be reduced to individual pitches. And as in Proust, music perception engages memory. The listener places what is heard in the moment against what has previously sounded, recognizing novelty, recurrence, transformation, and gradual or sudden changes in quality. Tempo change creates shifting time frames, and the reappearance of music already heard (earlier in the piece or from a different source altogether) merges past and present.

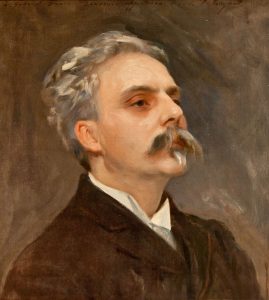

In real life, Proust too was a regular at numerous high-class salons in which music was the primary feature. His active social life served as a kind of research for his work chronicling the end of an era: a study of the behaviors, values, and power dynamics at work among the French aristocracy as it was succumbing to the forces of modernity and losing its potency. But it also brought him into contact with writers, painters, composers, fashion designers, and other creative types, celebrities in Parisian artistic circles. And it was in the setting of several salons which they both frequented that he first encountered, and was immediately taken with, the music of Gabriel Fauré. As Fauré’s biographer Jean-Michel Nectoux relates, Proust sought out Fauré’s company, listened to and studied his scores, believed his art deeply significant, and never ceased championing Fauré’s work.

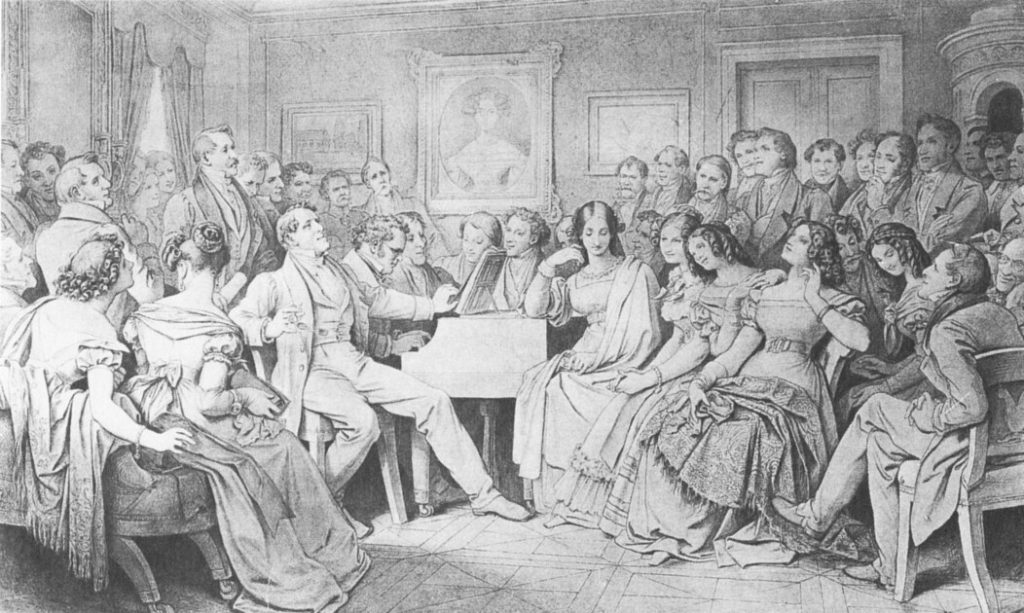

The Rise of the Salon

The salon, a private venue for musical performance, was highly disparaged during the 20th century, both as a sociocultural phenomenon and as the label for the music performed there. No tickets were sold, the performers were not paid, and the organizer was generally a female who hosted the event in her home and not a professional musician – all reasons to dismiss it as a setting for small-scale, amateurish activity and trivial music. But this misrepresents the milieu. Salons first appeared in France during the 1600s, rising to prominence during the 19th century when both public and private institutions replaced the court and the church as sponsors of musical activity. Music historiography has for the past 30 years undertaken to rescue the salon from its undeserved low status, dispelling the false association of “private” with “unimportant.” In truth, the greatest salons in Paris were a vehicle through which the efforts of “serious” composers like Chopin, Fauré, Debussy, and Stravinsky routinely received support, exposure, and acclaim that was indistinguishable from public success.

Gabriel Fauré attended many salons regularly, beginning in his 20s; he considered them a necessary part of his professional activity, and they played a major role in the dissemination and performance of his music throughout his life. Fauré’s published correspondence reveals that he enjoyed warm mutual friendships with three salonnières who were important patrons of the arts in fin-de-siècle Paris and who showcased his music extensively: Mme Marguerite de Saint-Marceaux; Countess Elisabeth Greffulhe; and Winnaretta Singer, Princesse de Polignac. All these women gave him tremendous social, moral, and financial support, which he acknowledges gratefully in the many letters they exchanged discussing his work, personal life, and accomplishments. He dedicated important compositions to them and treasured their enthusiasm for presenting his music before attentive and select audiences in intimate settings.

These influential taste-makers brought together a wide array of social and artistic luminaries, connecting and enlivening Paris’s diverse creative community. Proust was an equally devoted attendee of the Polignac, Saint-Marceaux, and Greffulhe salons, where he and Fauré had many occasions to meet. Charles Koechlin and Florent Schmitt were fixtures at Saint-Marceaux’s and Greffulhe’s salon concerts as well.

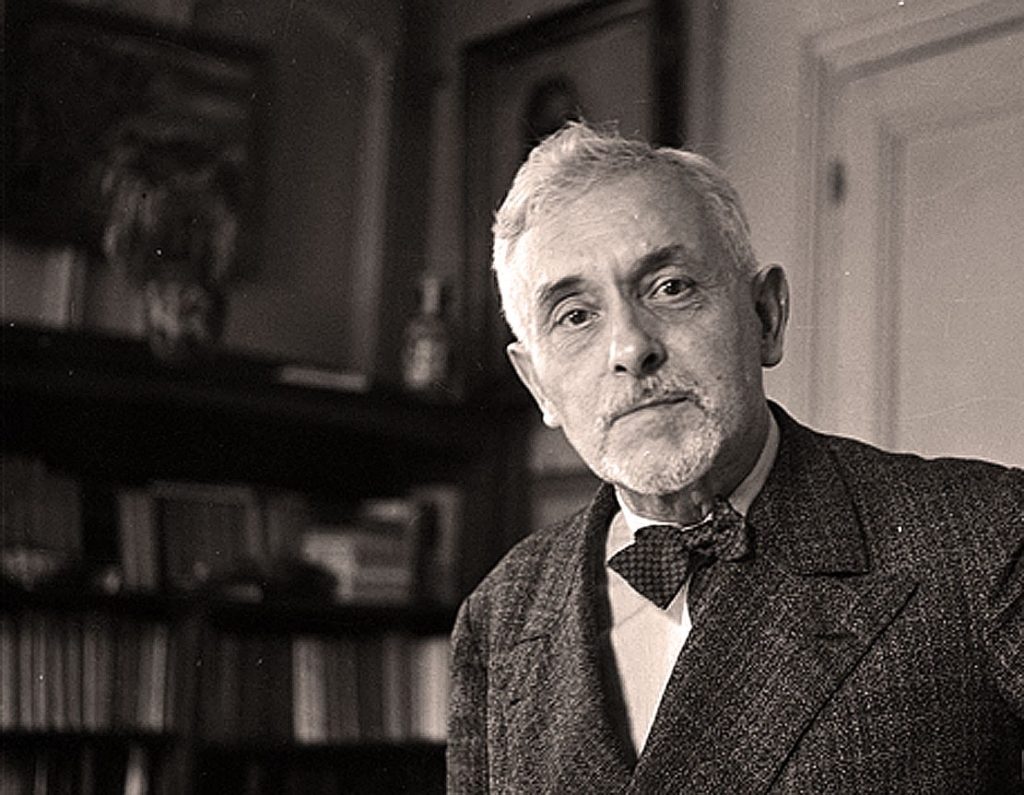

Charles Koechlin (1867-1950): String Quartet No. 1, Op. 51 (1911-13)

I. Allegro moderato (Very simply, with charm and suppleness)

II. Scherzo (Playfully, not too fast)

III. Andante quasi adagio (soft but expressive. Smooth and sustained)

IV. Final (Fast, moving)

An enormously prolific and eclectic composer who not only wrote 113 pieces inspired by a single film star, and the “Seven Stars” symphony, whose 7 movements were dedicated to different Hollywood icons, and who himself was the subject of a documentary fantasy titled “Tower of Dreams” – this was Charles Koechlin, a fascinating and original character who was a prime moving force in French music during his long life.

Koechlin was born in Paris into a wealthy industrial family. Though Charles’s father intended that he pursue a career in the army and sent him to engineering school, the youth’s poor health made military service impossible. Following his serious interest in music, he entered the Paris Conservatoire in 1890 to study harmony and counterpoint. Joining the composition class of Gabriel Fauré in 1896 was a turning point; Fauré’s influence on Koechlin’s style and aesthetic sense was profound, and he formed lifelong friendships with Florent Schmitt and Maurice Ravel.

Leaving the Conservatoire around the turn of the century without a diploma, Koechlin began professional life as an arranger, conductor, and composer. In 1909 he banded together with Schmitt, Ravel, and others to found the Société musicale indépendante, to promote a younger generation of French musicians with new ideas and distinctive voices who, like themselves, were being ignored by the more conservative Société national de musique. He was faithful to this cause and never failed to support the music of up-and-coming composers, with a tolerance for a wide range of musical approaches.

His own music, rhythmically and harmonically adventurous, gradually gained acceptance and renown, though little of it was published. Commercial success did not concern him; he composed slowly and methodically, without thought of fame, with only the desire to achieve the true expression of his inner thoughts. Nevertheless, he produced an enormous catalog including large-scale orchestral and choral works, songs, chamber and solo music, and film scores. He also wrote extensively on music theory and the nature of musical beauty. Eventually he felt confident enough to teach; among his pupils were Francis Poulenc, Germaine Tailleferre, and Darius Milhaud.

Koechlin drew inspiration from a wide variety of sources, in addition to his fascination with movie stars: romantic and symbolist poetry, Kipling’s Jungle Book (on which he based a series of 7 orchestral tone poems), and his own pantheistic, Mahlerian philosophy of nature. After his death, a series of recordings beginning with Antal Dorati’s interpretations of his Jungle Book collection has helped to revive interest in his unique and powerful musical voice.

Koechlin came rather late to string quartet composition, considering chamber music a “perilous domain” where he feared he could never equal the achievements of his admired teacher Fauré. But once he decided to venture into the field, he produced 18 chamber pieces within 10 years (along with solo piano, vocal, choral, and symphonic works). His String Quartet No. 1 was considered richly imaginative and highly refined by contemporary commentators.

The suppleness and broad leisurely pace of the Allegro moderato’s opening theme derives from Koechlin’s unique rhythmic approach of alternating measures of 6 beats and 4 ½ beats. Any feeling of irregularity is smoothed over by the quiet sustained chords and the rise and fall of the calm, linear melody, which all the instruments take turns singing in overlapping entries that sound like a conversation. As a closing gesture, violins, viola, and then cello play portions of a descending scale that finally comes to rest to finish the thought on a low D. The soothing character is maintained with the next section, which begins in minor but leads into a new major-key theme that is reminiscent of the opening one. Although the texture is more active, the melodic familiarity creates a uniformity of mood. Reversing direction from the way the first theme ended, this new line rises to the top of a scale and rests. What begins next in place of a conventional development section, usually an area that exploits musical tension among themes and keys, is more melancholy than conflicted, as both themes along with their countermelodies all “speak” at once in a new conversation that shares all that has been stated before. This, too, gradually quiets and stops, allowing the opening theme to reappear within a serene, widely spaced chordal texture. It is in this final portion of the movement after the second theme enters, that the passion and agitation displaced from the middle section arises, as if the conversation had become heated. But calm returns quickly with the final entrance of the opening melody and dispels any lingering anxiety.

The Scherzo combines short pizzicato and bowed textures along with almost constantly changing time signatures in a sparkling and lively tapestry in which the instruments again trade thematic entrances. The melody never quite concludes as much as winds down to prepare for a new beginning. The most striking moment is a sudden standstill followed by a heartfelt viola solo in the character of an operatic recitative; its unexpected appearance leaves the listener questioning what has come before, and what might possibly follow. But little by little the lively tempo and upbeat mood are recaptured and the movement rushes to a cheery finish.

The slow movement of the quartet is puzzling, somber and episodic. It opens with a long and meandering melody that is treated to frequent changes of texture and harmony that suddenly cadences and trails off. A brief, nervous contrasting section inserts itself, adding complexity to the situation, but it too trails off and is followed by a second, brief interjection of uncertainty. The opening section returns with even greater insistence, but its winding, questioning melody abruptly and mysteriously cadences as it did the first time, leaving the listener with many questions that seem to have no resolution.

The open-ended third movement’s uncertainty seems swept away by the vigorous and energetic Finale, which continues the episodic structure. For the first time the instruments play in extended unison as if finally in agreement, before launching into a jaunty fugue-like episode which leads to a reprise of the unison texture in even faster tempo. This is followed by a change of character: a slower, sweet serenade appears, but as this song works its way through its second verse, bits and pieces of the opening sneak in. A second, more dissonant contrapuntal section ensues, yet it too melts away into expressive lyricism. The movement, its energy expended, draws to a quiet close and we are left to contemplate the wild journey of emotions and psychological states the quartet has taken us through.

Florent Schmitt (1870-1958): Musique intimes (Inner Music), Book 2, Op. 29 (1898-1904)

Cloïtre (Cloister)

Sillage (Sea-Wake)

Brise (Breeze)

Lac (Lake)

Poursuite (Pursuit)

Glas (Knell)

While not a familiar name today, Florent Schmitt was celebrated internationally during his lifetime as a pioneer of French musical modernism. The Boston Symphony and the Strasbourg Festival Orchestra premiered his symphonic works. Widely performed in his home country as well, he published prolifically in all genres except opera, worked as music critic for three prominent French journals, earned the French Legion of Honor among many other awards, and used his influence to promote young musicians, jazz, and the new media of radio, film, and recording.

Schmitt was born in Lorraine, near the eastern border between France and Germany. His family nurtured the musical talent he showed early on, and at 19 he entered the Paris Conservatoire. There he enrolled in Gabriel Fauré’s composition class, where he met two important lifelong friends, Charles Koechlin and Maurice Ravel. The culmination of Schmitt’s 11-year stint at the Conservatoire was winning the Prix de Rome in 1900, after which he left Paris to travel and compose for the next four years. This was a productive period, resulting in several large-scale compositions acclaimed for their novelty and vitality, solidifying his reputation.

In 1909, along with Koechlin, Ravel, and several other young composers, Schmitt co-founded the Société musicale indépendant. Never willing to be associated with any stylistic movement or school, Schmitt pursued his personal musical path throughout his long life. His nickname “the Wild Boar of the Vosges” reflected both his Alsatian heritage and the dramatic passion his music expressed. He showed no interest in teaching, but supplemented his composing with 30 years’ work as a music critic. The fiery temperament his music revealed often showed through in his criticism, which was famous for its sarcasm, and he was notorious for his outbursts during concerts if either the music being performed or the behavior of the audience displeased him.

Since his death, Schmitt’s music has not enjoyed much exposure in the U.S., but the last 20 years have seen an increase in performances and recordings. One of his champions is music director JoAnn Falletta, who recently performed and recorded six of his large orchestral compositions (including two world premieres) with the Buffalo Philharmonic and conducted the North American premiere of his Antony and Cleopatra suite with the Virginia Symphony Orchestra.

Musique intimes (Inner Music) is an early work, composed during the Prix de Rome period when he traveled throughout Italy, Greece, Turkey, Russia, and North Africa. Schmitt’s experiences in distant lands and cultures stimulated his creativity; musicologist Jann Pasler notes that travel represented for him “a symbol of freedom and a release from intellectual and social boundaries.”

Cloister evokes the meditations of a mystic. A chant-like opening repeats a rising figure, ambiguous in tonality, that falls back to where it began, lingering on this resting point with another repeated figure that ascends softly up the keyboard to conclude the brief first section. The opening chant then reappears, higher in register, but the prayer has become more impassioned; it is louder and three times as long. The tempo presses ahead, and the music expands, reaching into both higher and lower registers, with thickened textures, repeating itself before gradually descending to its original starting place. Again the opening chant returns, and the final expansion is even greater: higher, still longer, louder, more dissonant, obsessively repetitive, until the prayer ends, exhausted.

Sillage maintains a swinging barcarolle rhythm throughout, reminiscent of a boat’s rocking upon the waves. But this sea is not calm. A jagged melodic figure jumps back and forth in various registers in a rhythmic pattern that does not match the steady one-two beat of the left hand. The waves appear to swell three times as the two hands move in contrary motion before briefly pausing at the crest and settling back to the uneven tossing of the boat on choppy waters.

Brises explodes in rapid flourishes that sweep up and down the keyboard like blustery winds. Here the arpeggiated texture remains consistent throughout, except for two moments of silence followed by slower rhythms. These momentary lulls punctuate the piece. The first, marked “expressively,” precedes one final loud gust, and the second, marked “weakening,” is just before the end.

Lac unfolds in one continuous rumination over the calm undulations of a placid lake. The melody rises and falls without ever coming to rest or cadence. There are only brief points where the rhythm slows and lower registers are engaged before the next thoughts begin. Textures are cumulative, growing more complex as the piece proceeds to its emotional high point, marked by octaves in high register that recede in intensity as the piece draws to a close.

Poursuite tells its story through rhythm. The two hands open the piece simultaneously but immediately start following each other up and down the keyboard; the right hand resting on the third of each group of four makes it sound breathless. The next stage of the chase injects more rhythmic tension: groups of four in the left opposing groups of three in the right. That situation intensifies once more as the right hand’s groups of three move into double time: now it’s four against six. Rhythmic instability continues to the end as the piece alternates all three of these rhythmic patterns before fading into the distance. Who was chasing whom?

Glas restores the somber mood of the opening piece in the set with the tolling of massive bells that sound and resound a death knell three times. Each statement of the tolling bells dies away and we hear a mournful chant, as from afar, like a memory of deep sorrow. We hear the final tolling of the bells as a constant and terrible reverberation, as if the bells of many steeples joined one by one to announce the death knell, while the chant, more eerie then ever, draws itself out and then dies away.

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924): Piano Quartet No. 2, Op. 45 (1885-86; published 1887)

I. Allegro molto moderato

II. Allegro molto

III. Adagio non troppo

IV. Allegro molto

Shortly before Gabriel Fauré’s death, American composer Aaron Copland published a lengthy essay on Fauré’s career and his vast musical output, praising him as the greatest living French composer and regretting that he was not better appreciated outside of France. The world desperately needs Fauré today, Copland concluded, for his “calm, his naturalness, his restraint, his optimism, his great art.” And at the time of his passing just a few weeks later, Fauré was indeed regarded as the most prominent composer of his generation as well as a brilliant, insightful teacher who guided many younger musicians to develop their technique and find their individual voices. The mutual devotion between teacher and pupils was strong; composers like Koechlin, Schmitt, and Ravel supported and honored him all their lives, and he steadfastly promoted their work and careers in turn.

Growing up in an educated family in southwestern France, Fauré’s musical talent emerged early, and his parents determined to prepare him for a career as a choirmaster. At the age of 9 he was sent to the École Niedermeyer in Paris, where he lived and studied for 11 years. Niedermeyer’s curriculum emphasized study of Gregorian chant, the choral masterworks from Palestrina through Bach and Handel, and the great French keyboard composers of the 17th and 18th centuries. The sounds and structures of these periods of early music infused Fauré’s own compositional thinking and contributed to his unique sound and melodic approach.

For the next 25 years, Fauré’s life consisted of constant work as an organist and choir director, first in the provinces and finally at a series of important churches in Paris. He combined this with private teaching, networking in musical salons to improve his status and cement his connections into Parisian artistic circles, and intense compositional activity. After the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, he was instrumental in founding the Société nationale de musique, dedicated to the nurturing and promotion of the characteristically French musical genres of song and chamber music, and this affiliation brought performances and wider exposure of his music. However, the numerous occupations he maintained to support himself and his family left him with limited time for composing – a frustration he would feel his entire life.

By his 50s, Fauré’s efforts had led to wider fame and recognition; he was celebrated in the most important salons in Paris and appointed to the composition faculty of the Paris Conservatoire. In 1905 he was elected to the Directorship of the Conservatoire, a position he held for 15 years and where he proceeded to institute important reforms such as requiring courses in music history and incorporating symphonic music into the performance studies. While the position brought increased fame, it came with a heavy workload and tremendous stress that was compounded by worries over his increasing deafness. Nevertheless, he continued developing and deepening his compositional ability, and the works from the last period of his life, from the early 1900s until his death in 1924, are among his most distinctive and powerful: his only opera Pénélope, three great song cycles, and a series of chamber compositions with piano as well as his only String Quartet.

Almost twenty years ago Sir Neville Mariner and the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields recorded Fauré’s beautiful Requiem along with two tributes to their beloved teacher written after his death: Charles Koechlin’s Chorale on the Name of Fauré, Florent Schmitt’s In memoriam Gabriel Fauré. This artifact constitutes a touching testimony to the bond among three original artists, who strove always to enrich and develop French musical art and whose dedication to each other never failed.

Fauré’s chamber music is one of the more significant portions of his output. In a 1903 letter to his wife, he reveals why he valued the genre so highly: “You’re right to value chamber music as much as you do. Indeed, in it… you’ll find real music and the sincerest translation of a personality.” It appears that he believed through chamber music he could express his innermost thoughts and feelings.

The Piano Quartet No. 2 dates from the mid-1880s, a time of hard work and professional frustration with the slow progress of his career. Indeed, passion runs high as the furious piano and agitated unison strings open the first movement. The pathos of the second theme, to which the anger gives way, seems like a personal outcry. It is introduced by the solo viola and then the violin expands it lyrically, with more delicate and calmer accompaniment before the fierce mood of the opening returns. The middle (development) section alternates a new subdued theme with versions of the lyrical second theme, which gradually takes on the agitation of the opening and explodes into the reprise of the opening, with the furious final statements of the coda subsiding into a surprisingly gentle close.

The thrilling Scherzo second movement continues the mood of vehemence – but somewhat less angrily than before. This time the atmosphere is icily diabolical. The piano’s rapid runs seem almost playful, touched with the sardonic. Fauré inserts a mad waltz before the dazzling final return of the opening flourishes.

The third movement is truly other-worldly. Fauré’s biographer Jean-Michel Nectoux observed, “The sense of space it creates, rapt and profound within a narrow range of notes, marks it out as being truly the music of silence.” Fauré himself has provided the best description: “In the Andante I can remember having translated – and almost voluntarily – the very distant memory of bells ringing, which in the evenings would reach us when the wind blew from the west. Over this drone a vague reverie goes aloft, which, like all vague reveries, would be untranslatable by literary means. Yet isn’t it often that something external thus lulls us into thoughts of a sort so imprecise that in truth they are not thoughts, and yet they are something in which we take pleasure? The desire for nonexistent things, perhaps. And that is indeed the domain of music.”

The Finale restores the high energy and texture of the opening: unison strings against an undulating piano. More muscular and driving, less jittery, this movement propels us forward while also bringing us back in time: recapitulating melodies and ideas from each of the earlier movements in a wholly unique, idiosyncratic approach to cyclic form. The wild and ecstatic coda propels the work to a triumphant close.

Linda Berna