Soto String Quartet Program Notes

For their concert debut, the Soto String Quartet have chosen a program that perfectly reflects the group’s philosophy of energy through art, presenting one traditional European composition contrasted by a modern work of Latin origin.

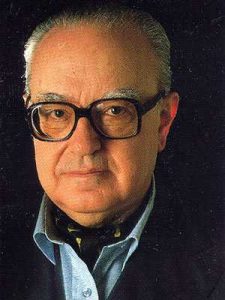

Alberto Ginastera: Argentina’s Greatest Composer

Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983), String Quartet No. 1, Op. 20, 1948

The concert opens with Alberto Ginastera’s String Quartet No. 1, Op. 20, from 1948. Ginastera, universally acclaimed as Argentina’s greatest composer, was born in Buenos Aires in 1916 and died in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1983. As a composer and an educator, Ginastera initially held a strong commitment to galvanizing an Argentinian musical identity. However, ongoing political and artistic conflicts with oppressive ruling regimes gradually caused him to spend the latter part of his life in the United States and Europe.

Three Periods

Ginastera grouped his music into three periods: Objective Nationalism (1934 –1948), Subjective Nationalism (1948 –1958), and Neo-Expressionism (1958 –1983). Ginastera’s String Quartet No. 1 can be viewed as a transitional work, looking forward to the composer’s more conventional international modernism while still being born of the soil of his native land.

Relentless Rhythmic Ferocity

The quartet comes shockingly into existence in the opening Allegro violento ed agitator, influenced by the musical language forged by the 20th-century Hungarian composer Bela Bartok and the South American gaucho’s “malambo” dance. Relentless rhythmic ferocity rules as fragments of folk-inspired melodies are swept into the storm. The dark drama resumes unabated in the second movement, Vivacissimo, which compounds a menacing quality on top of the stark anger of the first movement. The toccata-like rhythm is audibly lighter here, helping to suggest the advent of a traditional scherzo.

Expression in Latin Imagery

The pent-up energy of the first two movements is finally dissipated in the mournful homophony of the Calmo e poetico. Again, borrowing from the pen of Bartok, Ginastera expresses a soulfulness that is all his own. The movement opens and closes with an allusion to a classical Guitar, with the sounds of the instrument’s six open strings played simultaneously — an obvious grounding of the expression in Latin imagery.

The mood of the final Allegramente rustico is a dramatic shift from all that has come before. This rondo-like movement incorporates Argentinian rural dances into a neoclassical vessel. This joyous and rollicking ride goes on just long enough to distance us from the darkness that pervaded the rest of the quartet

Schubert: A Composer of More Than Lieder

Franz Schubert (1797-1828), Quintet in C major, D.956 “Cello Quintet”

Conventional wisdom attributes the other-worldly undertones of Franz Schubert’s String Quintet in C major, D.956, to the composer’s sense of knowing that death was on his doorstep. But the facts dispute this convenient interpretation.

Schubert was admired in his day as a prolific composer of art song, but he struggled to find acceptance for his large-scale instrumental works. Completed in late September or early October 1828, the composer thought very highly of his new string quintet and enthusiastically offered it to his publisher Heinrich Albert Probst, who rejected it out of hand. A few weeks later, Schubert’s health took a sharp decline as his syphilis affliction and the toxic treatments he was receiving for it conspired to produce infection and painful death by November 19 of the same year, at age 31. Schubert would never hear his cherished quintet performed. It remained unknown until it was premiered in 1850 by the Hellmesberger Quartet.

Reception Over Time

Undeniably accurate is the reception that grew around this work for two violins, viola, and, unconventionally, two cellos. The C major Quintet represented a high mark in chamber music literature and illuminated a new path of expression that would directly influence the musical language of future generations.

It was not in form and structure that the composer challenged the musical order of the day. That frontier had already been exploited a few years earlier by Schubert’s musical idol, Beethoven, whose Late Quartets wreaked havoc upon the musical conventions of his era. It is in their soundscape that this and other last works of Schubert break new ground.

The German musicologist, dramaturge, and stage director Wulf Konold described what the composer produced as “…a wash of sound – a field built up of generally static harmonies and given latent movement by repetitions of small figures.” To Konold, this device was used as a replacement for traditional motivic writing.

Ground-breaking Scale

The opening Allegro ma non troppo contains an obvious example. This, the longest single movement of chamber music composed up to its time, lasts for over one-third of the entire piece. The opening C major chord seems to emerge from the mist and reveals the new musical language that Konold identified. Only when the movement proper begins is this trance-like state interrupted. There are also ongoing unexpected harmonic turns in which Schubert communicates what words, melodies, and motives cannot. If one is seeking the melodic magic for which the composer is justly famous, listen for the cello duet that takes center stage two minutes or so into the performance.

Free of Earthly Concerns

Konold’s convention is also at play in the Adagio. Earthly concerns are absent; time is meaningless. The mood is violently interrupted by the turbulence of the central section, where the shock is rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic. Eventually, the “beast” is calmed. The opening music returns, subtlety impacted by the turbulence suggested by a running 32nd-note passage in the second cello.

A Symphonic Experience

The most symphonic sounds of the quintet arrive in the Scherzo as C major blazes back into the spotlight. By using open strings in the lower instruments, a quantity of sound is produced that seems impossible for just five instruments. This is as animated as Schubert’s music would ever be. The gentle and reflective middle section is unusually long and re-establishes the mood of the opening sections of the first and second movements of the quintet. The symphonic magic is relaunched through unison rhythmic acceleration, making the music even more exciting than when it first appeared.

A Fitting Farewell

The high spirits of the Allegramente rustico finale appear almost as anathema to all that has come before. The most traditional movement of the quintet, it bursts with joy using a Hungarian-inspired melody while adding some Viennese spice. Even still, Konold hears a “last dance,” as harmonic tensions increase menacingly. Schubert was not content to take us home in the traditional style of Haydn, ending not with a simple period but with a shadow of a doubt.

Soto String Quartet performs at 6:30 p.m. November 9th at Guarneri Hall, 11 E Adams St Ste 350A, Chicago. $10-$40. 847-780-6720 or guarnerihall.org.