Violinist Timothy Chooi: Startlingly Deep

Hearing Timothy Chooi for the first time – even on YouTube and through tiny computer speakers – the quality of his sound is startlingly deep. In contrast to generations of laser-accurate, Juilliard-schooled violinists, Chooi’s music-making unfolds in a variety of evolving voices, held together by a strong family resemblance. Reading his artist bio reveals one cornerstone influence on Chooi’s career: Pinchas Zukerman.

Violinists’ Ultimate Finishing School

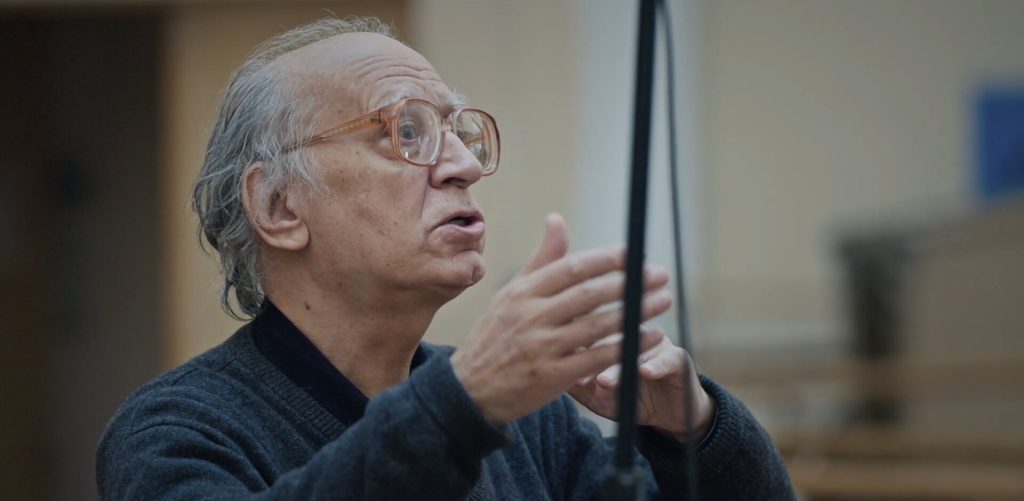

For some violinists, the now 74 year-old Zukerman is the ultimate finishing school. For Chooi – who grew up in Victoria, BC, playing violin with his older brother – Zukerman was the beginning of an obsession with virtuoso violin playing, starting at age 9 with a chance meeting when the violinist/conductor was touring Canada with Ottawa’s National Arts Centre Orchestra. For the decade that followed, Chooi spent his summers with Zukerman in Ottawa.

“We spent hours and hours and hours,” recalled Chooi, “working on posture, making violin playing as simple as possible….the mechanism of the arms, how all the joints communicate with each other. He said, ‘This is your bank account.'”

Chooi also took lessons from Zuckerman’s inside stories about how a musician’s world could work. For example: when the young Zukerman would fly in to play a concerto with an orchestra, he would often ask to play the concert’s second half anonymously with the second violins. His humility moved many. Sir Georg Solti was not: “Well, do you know the piece?”

Studies at the Curtis Institute and the Julliard School, plus a post-Zuckerman succession of mentors and master classes led by some of the top names of the violin world further shaped Chooi’s development. Now, at age 28, Chooi is an assistant professor at the University of Ottawa, is on the Colbert Artists Management roster, and has performed with many of the world’s great orchestras, including the NDR Radiophilharmonie, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Brussels Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, National Arts Centre Orchestra, Toronto Symphony Orchestra, Montreal Symphony Orchestra, and the Sichuan Symphony Orchestra. In competitions, he placed first in the 2018 Joseph Joachim International Violin Competition in Hannover and second place in 2019 in the career-making Queen Elisabeth International Violin Competition in Brussels. In one capacity or another, he has worked with Ida Kavafian, Pamela Frank, Catherine Cho, Christian Tetzlaff, and Anne-Sophie Mutter, with whom he will do a summer-long tour with her Mutter Virtuosi. One wonders how he was able to find his own voice through work with such towering personalities and high-pressure competition circumstances. “It has been confusing and liberating,” he admits. “The handcuffs” – his word for repertoire restrictions, technical perfection requirements, and concepts of proper interpretation – “are off.” And then what?

Many of the individual qualities that emerge in Chooi’s playing, such as the expressive finger slides known as portamento, have seldom been heard since the heyday of Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962). Yet another manifestation of his sound is likely to be heard from the soulful, exalted, enigmatic Berg Violin Concerto, one of the summits of the literature Chooi learned and programmed for concerts that would eventually be canceled during the lockdown. Of course, the colors he employs in the Bruch Violin Concerto No. 1 are slimmed down when playing Mozart. These days, his art now seems so intuitive that this articulate violinist can’t always explain why he does what he does – and frankly, doesn’t need to.

Freedom to Put Your Stamp on the Repertoire

“At a certain age, you have the freedom to put your stamp on the repertoire,” he said. “As I get older, I’m processing all the things the mentors gave me. There are moments where they say, ‘no portamento there.’ But I’m out of school. I’m crystallizing myself as an artist. I’m asking, ‘Why am I doing things this way? Why have I been doing this for so long? What brings out the best in me? How do I want to present myself as a violinist?’ There are better answers and worse answers.”

Such questions can intensify when revisiting his hometown of Victoria: “It’s humbling to go back and hear the pop culture music listened to by my non-musical friends. The more you’re into classical music, the more you realize this is very different from what others do. We have a responsibility to bridge that gap between musicians and non-musicians. I want to be the key to open that door.”

You Can Never Get it Back

Social media and YouTube have offered great possibilities for Chooi to bring classical music to non-musicians. However, he recognizes social media’s limitations – and invasiveness: “Once you start selling your personal story, you can never get it back.”

Ultimately, Chooi shares his story through the music he chooses to program alongside his collaborator, pianist Changyong Shin. One starting point is his pan-cultural identity. The ethnically Chinese Chooi was born in British Columbia but at one point moved to Florida with his Chinese-Indonesian mother and Chinese-Malaysian father – has chosen to anchor his upcoming Guarneri Hall program not with the Germanic cornerstones of Beethoven and Brahms, but rather with a distinctive chronological and stylistic spread from Grieg (1843-1907) to the contemporary Ukrainian composer Silvestrov (b. 1937). The uniting factor is the undercurrent of extreme violinistic virtuosity.

Grieg’s 1886 folk song and dance-based Violin Sonata No. 3 Op. 45 – the most popular of the composer’s three violin sonatas and one that Chooi played at the Queen Elisabeth Competition – was premiered by Russian violin virtuoso Adolph Brodsky, namesake to the current UK-based Brodsky Quartet. “Romance,” by New England composer Amy Beach (1867-1944), is a songful and deep work written in 1893 for the great Maud Powell who gave the US premieres of the Sibelius and Tchaikovsky violin concertos). “Nocturne and Tarantella,” Op. 28 by Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937), with influences from Italy to Spain and even the Middle East, was sketched in 1915 when the composer was out drinking with noted violinist Paul Kochánski after a Mediterranean sojourn.

Ukraine’s Most Prominent Composer

Like many musicians, Chooi has been playing the music of Ukraine’s most prominent composer, the 85-year-old Valentyn Silvestrov, a one-time member of the Kyiv avant-garde.

Even long before the Russian invasion, Chooi was playing Silvestrov’s 1981 Postlude No. 2 for Solo Violin. Silvestrov’s work can be heard as a solo violin voice in the wilderness, calling out to anyone in earshot and luring them into a state of introspection. Purely as music, the piece will likely fit in well with the rest of the program. Silvestrov is widely quoted as saying, “My music is a response to and an echo of what already exists.” But Chooi’s continued showcasing of the piece is no surprise, considering that he’s a founding member of The VISION Collective, musicians and composers who champion immigrant and refugee causes and diverse, socially aware art.

Bridging the Gap

The final piece of Chooi’s cultural jigsaw puzzle is his violin, the “Engleman” Stradivarius on loan from the Nippon Music Foundation. Like many Strads, it’s a bit of a diva. “You open the case and just pray it had a good sleep,” Choi said. “I nicknamed it ‘The Dragon.’ It can be lazy and not speak at all. It has this choking sound, and then in the middle of a concert, it roars. It breathes fire. You just have to figure it out. It’s like a human being. You feed it properly, water it properly.”

In addition to his teaching and his traditional concerts, Chooi also performs with his older brother Nikki, known collectively as “The Chewey Brothers.” With so many activities in the air, what kind of music constitutes Chooi’s “secret garden”? What is his musical fallback? What constitutes musical recreation? “Film scores,” he said.

But even that private interest has a public component. Chooi loves how film scores bridge the gap between popular culture and classical music. He loves how John Williams has maintained what he calls a musical “duality” in his life, appealing to the masses while pushing them toward greater orchestral sophistication.. Where this comes together in Chooi’s current repertoire is Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s 1945 Violin Concerto, which incorporates music recycled from some of the composer’s great Oscar-winning film scores in his trademark lush, post-Richard Strauss style. However, the piece is more challenging than it might sound. Conductors and orchestras may find themselves challenged – if they aren’t ready for what is coming. “It’s such a greatly orchestrated piece,” says Chooi, “so performing it is a big team effort.”

Hear Timothy Chooi in his Guarneri Hall concert debut on Tuesday, March 28, at 6:30 PM.