Program Notes: Metamorphosis of Romanticism

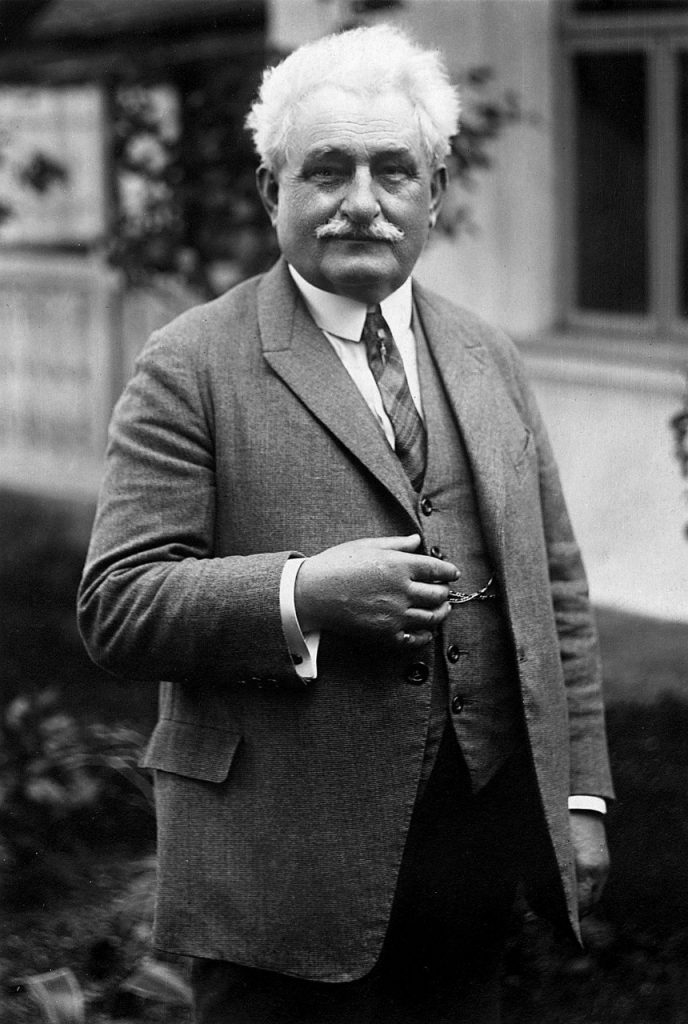

LEOŠ JANÁČEK (1854-1928) POHÁDKA FOR CELLO AND PIANO (1924)

The Czech composer Leoš Janáček held a lifelong affinity for Russian culture that permeated his creative process. He read extensively in the Russian language, co-founded a “Russian Circle” in Brno devoted to its teaching, and from 1876 began composing works based on Russian themes.

Janáček’s Pohádka, or “Tale,” is based on an epic Russian poem by Vasily Zhukovsky, “The Tale of Tsar Berendyey.” The piece was conceived of as scenes from the story rather than a complete rendering of the tale. Janáček first composed Pohádka in 1910, during a time when he remained under recognized as an artist and battled self-doubt. He later revised his original three-movement version several times, beginning with the addition of an additional finale in 1912. In 1924, Janáček returned Pohádka to a three-movement form and made many other changes as well. This third version is the one most often performed today, including tonight’s concert.

An excerpt from Pohádka can be heard in the soundtrack to the 1988 film, “The Unbearable Lightness of Being.”

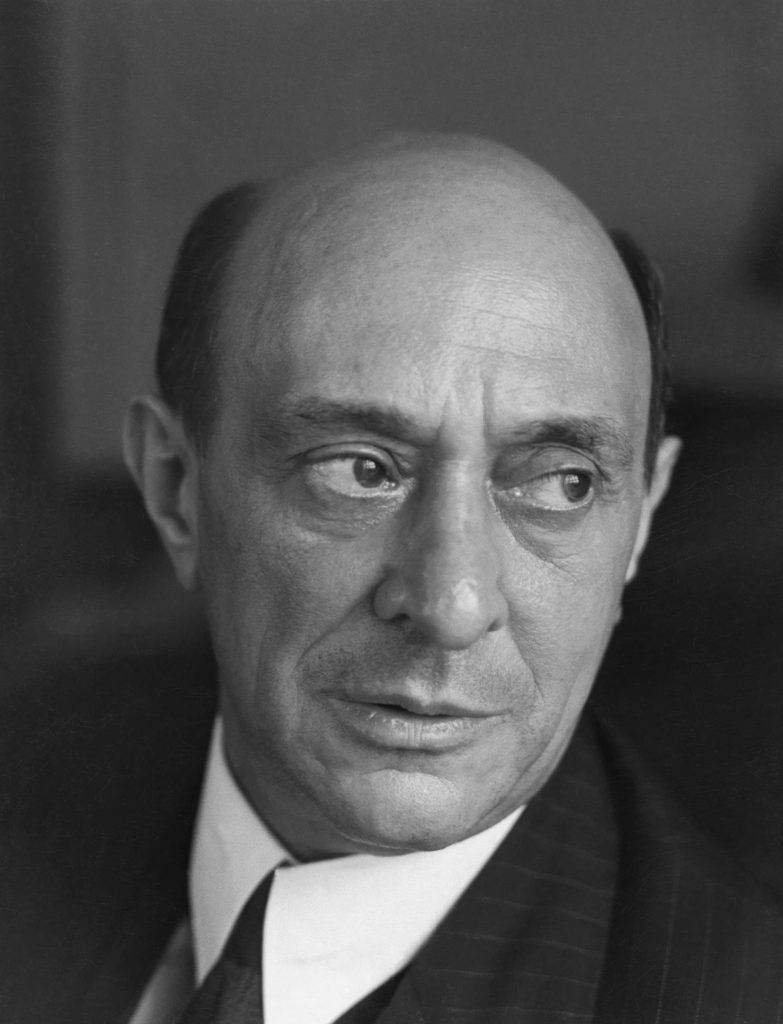

ARNOLD SCHOENBERG (1874-1951): PHANTASY FOR VIOLIN WITH PIANO ACCOMPANIMENT OP. 47 (1949)

Arnold Schoenberg began his career in 1890s Vienna, totally embracing the fully developed (and often opposing) romantic traditions of Brahms and Wagner. His earliest important work, written in 1899, was the highly romantic tone poem, Transfigured Night, for string sextet. Gustav Mahler took Schoenberg under his wing as a protégé after encountering his early works. As Schoenberg’s influence grew, he became the leader of what came to be known as the “Second Viennese School.”

In the early 1900s, Schoenberg began to break free of traditional harmony, first with so-called extended tonality, and later with the elimination of key signatures altogether. Schoenberg detested the term “atonal” that was applied to this style of composition, calling it misleading. From 1923, he began to use the serial or “12-tone” compositional technique that would polarize the musical world. Schoenberg later returned to more conventional tonalities but continued to compose music that would sound eternally modern. In 1933, Schoenberg emigrated to the United States to escape Nazi persecution. He eventually settled in Los Angeles and continued to extend his influence through his writing and teaching until his death in 1951.

Phantasy for Violin with Piano Accompaniment was commissioned by violinist Adolph Koldofsky, who began an association with Schoenberg when he moved to Los Angeles in 1945. Schoenberg is said to have composed the violin part in full before writing in the piano part a week later. Koldofsky premiered the Phantasy in March 1949.

Schoenberg’s textbook “Structural Functions of Harmony” classified the genre “Fantasy” as one of the so-called “free forms,” meaning free of formal restrictions. This freedom in the Phantasy Op. 47 is most apparent in the sometimes improvisational-sounding transitions between material. Listeners will find that the Phantasy has its share of the Schoenberg dissonances and sharp punctuations that can be a barrier to audience acceptance. Less immediately apparent is the vividly romantic nature of the work, with its elegantly distilled melodies and Viennese waltzes. Schoenberg was labeled a modernist because of his embrace of dissonance and technical innovations. But underneath the highly specialized experiments and dissonant chords, Schoenberg remained a romantic through various modes of expression throughout his career. The Phantasy was Schoenberg’s final instrumental work.

FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886): LIEBESTRAUM No. 3 (1850)

Franz Liszt’s meteoric rise to fame as a virtuoso pianist began in Vienna at age 11. He became an instant sensation as a performer, touring extensively in his earlier years while composing relatively little. Liszt was profoundly influenced by violinist Nicolo Paganini, whom he heard in Paris in 1832, and by Frédéric Chopin, whom he befriended in the 1830s. His fame continued to grow, and by the 1840’s the poet Heinrich Heine had coined the term “Lisztomania” to describe the sensation that the pianist caused wherever he played.

Liszt matched dazzling virtuosity and command with an unprecedented level of theatricality that held audiences in a hypnotic trance. The cult of personality around the pianist was unlike anything before him, and he earned enormous fees. By the 1840’s Liszt had become a great patron of humanitarian and cultural causes, which only further endeared him to the world.

In 1847 Liszt met the Polish Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, who persuaded him to concentrate on composition. At age 35 and at the height of his powers, Liszt retired from public performance, which further fueled his exalted public status.

The following year, Liszt settled in Weimar, where he had been appointed Kapellmeister Extraordinaire. In the twelve years that followed he would write the works for which he is most famous, including three Liebestraume, or “Dreams of Love,” written in 1850 as solo piano transcriptions of songs previously written for high voice and piano. Liebestraum No. 3 is based on “O lieb, so lang du lieben kannst” by Ferdinand Freiligrath. It is among the most popular of Liszt’s compositions and one of the most recognizable representatives of the 19th-century Romantic Tradition.

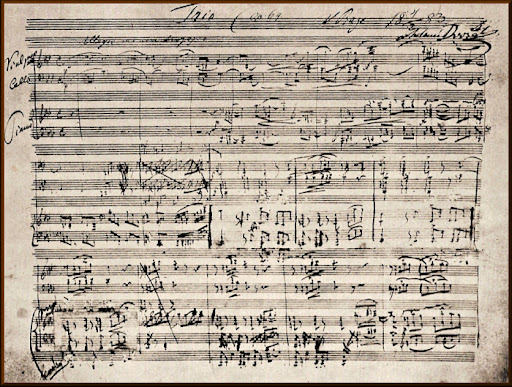

ANTONIN DVOŘÁK (1841-1904): PIANO TRIO NO. 3 IN F MINOR OP. 65 (1883)

Antonin Dvořák was an obscure Czech composer when, in 1874, he won the Austrian State Prize for composition. As a jurist, Johannes Brahms was deeply moved by Dvořák’s work and became his champion. Brahms eventually brought Dvořák’s music to his publisher, Simrock, and later to the critic Louis Ehlert who published an essay about Dvořák in the Berlin Nationalzeitung in 1878. It was the beginning of international fame for Dvořák. Brahms would remain a prolific supporter of Dvořák, and Dvořák a loyal friend to Brahms, until Brahms’ death in 1897, after which Dvořák assumed Brahms’ seat on the Austrian State Prize jury.

Dvořák composed two piano trios before he had become widely known and two more in the years after he had become famous. The fourth of the set, known as the “Dumky,” garners the most attention, making the Trio #3 in F minor Op. 65 a relatively overlooked masterpiece.

Dvořák began writing out the Piano Trio No. 3 in February 1883, shortly after the death of his mother. His work on the piece was unusually prolonged: Dvořák usually worked quickly, composing works within just a few weeks, but he worked on the F minor trio for nearly two months before finally completing it on March 31,1883.

By this time, Dvořák’s had become famous due to Ehlert’s essay and Simrock’s publication of Slavonic Dances. In the F minor trio, we can hear Dvořák moving away from Slavonic style in deference to a Viennese public whom he characterized to the conductor Hans Richter as “prejudiced against a composition with a Slav flavor.”

Dvořák’s Trio No. 3 was first performed on October 27, 1883, at a concert in Mladá Boleslav, with violinist Ferdinand Lachner, cellist Alois Neruda, and Dvořák himself playing the piano part. The piece was published shortly afterwards by Simrock.