Program Notes: Reveries

CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918): RÊVERIE FOR SOLO PIANO (1880-1884)

An Early Reverie

Rêverie for solo piano seems to have been composed by Debussy sometime between 1880 and 1884, at the beginning of his career. The composer’s emerging voice is already clear and recognizable in Rêverie. The work is an exotic and dreamlike exploration of the textures and harmonies that Debussy would develop with even greater narrative drama in his later works.

Regrets

Several years later, Debussy’s publisher, Eugene Fromont, decided to publish Rêverie to the composer’s great displeasure. Debussy wrote in a letter to Fromont:

I regret very much your decision to publish Rêverie. I wrote it in a hurry years ago, purely for material considerations. It is a work of no consequence, and I frankly consider it to be no good!

Despite Debussy’s regrets, Rêverie quickly became both a commercial and critical success and is often credited with significantly influencing the early development of jazz harmony.

CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918): DANSE FOR SOLO PIANO (1890)

(Originally: Tarentelle Styrienne)

Snakebite Fever

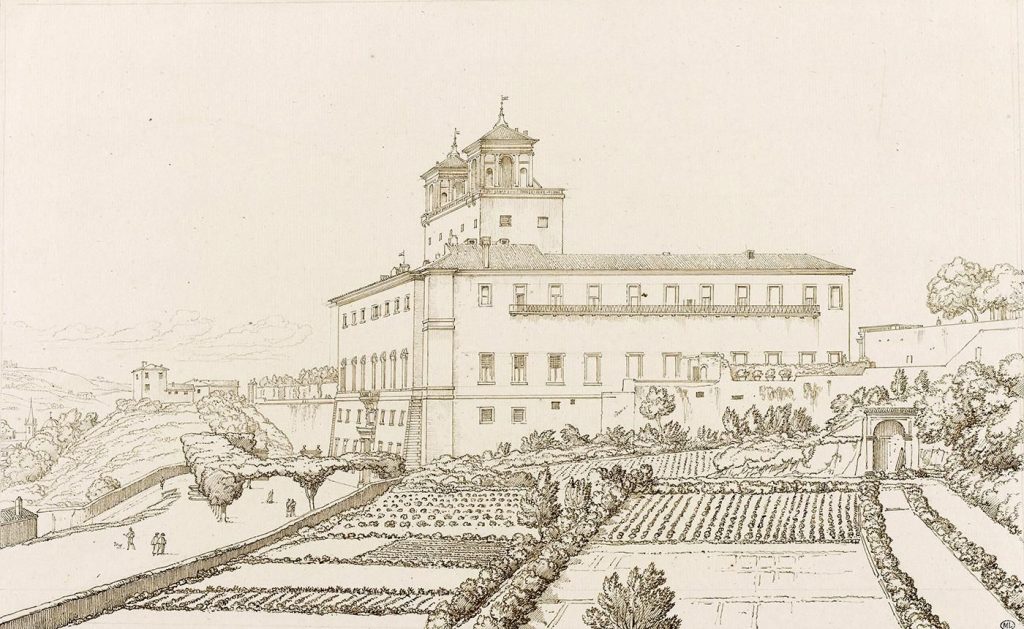

In 1883, young Debussy won the prestigious Prix de Rome. His prize required him to spend an extended period at the French Academy in Rome, to further his studies. On his return to France in 1890, Debussy wrote Tarentelle styrienne for solo piano, based on the tradition of a fast work danced as a cure for the venom from a tarantula bite. Debussy paired his Tarentelle styrienne with another work for solo piano Ballade slave, and the two pieces were published together by Choudens in 1891. In 1903 Debussy separated the two works, made a few minor revisions to Tarentelle styrienne, and Fromont published it as Danse.

Following Debussy’s death in 1918, Maurice Ravel adapted Danse into an arrangement for full orchestra. Ravel’s orchestration of Danse was first performed in 1923, and is heard more often today than the original, but Debussy’s 1903 version continues to be performed in solo piano recital programs.

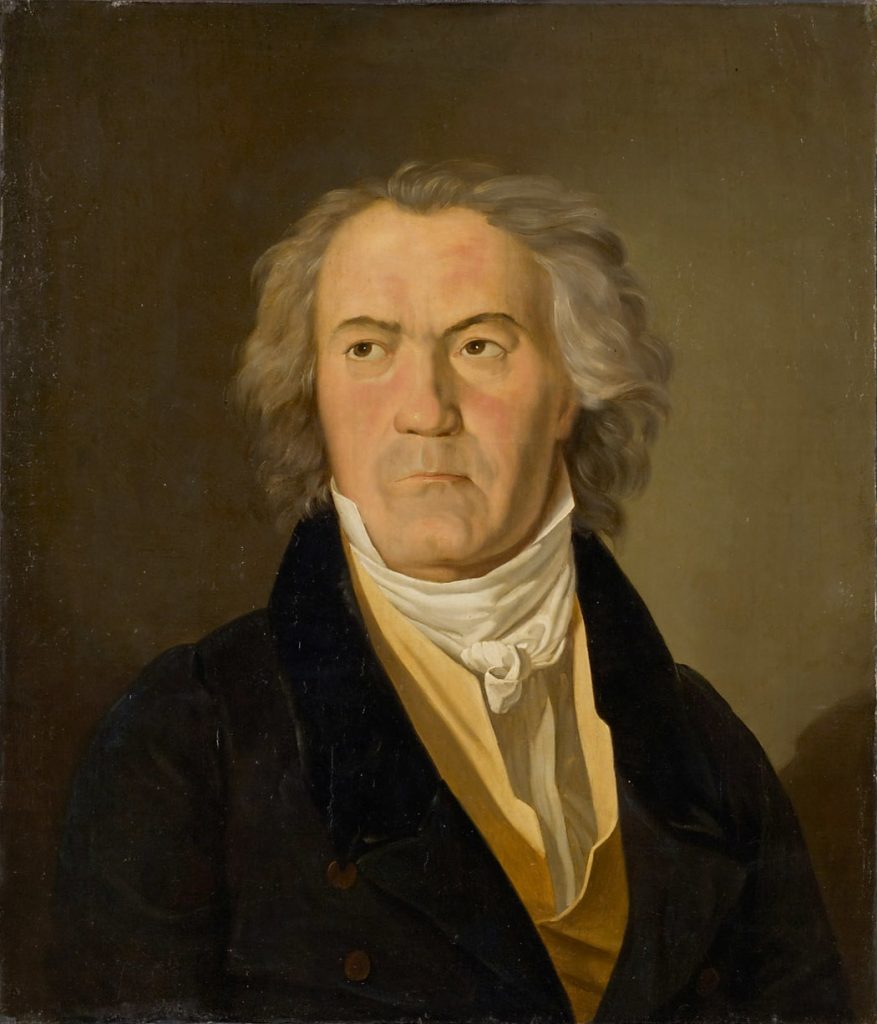

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827): PIANO SONATA NO. 28 IN A MAJOR, OP. 101 (1817)

Impressions and Reveries

Beethoven described his Piano Sonata no. 28, Op. 101 as “a series of impressions and reveries.” Sketches for the work first appeared in the composer’s notebooks as early as 1815-16. Beethoven worked on the piece in Baden, just south of Vienna, over the summer of 1816 during an unhappy time in his life. Following the death of his brother earlier that year, Beethoven had assumed guardianship of his nephew Karl. The result was a series of almost constant battles with Karl’s mother and with Karl himself.

Baroness Dorothea von Ertmann

On July 19, 1816 Beethoven offered his completed Op. 101 sonata to the Leipzig publishing house Breitkopf and Härtel, but was rejected. Later, the Viennese publisher Steiner took up the Op. 101 and published it in January of 1817. Beethoven dedicated the piece to his pupil, Baroness Dorothea von Ertmann. He sent a copy to von Ertmann in February of 1817 with a note: “Receive now what was often intended for you and what may be a proof of my affection for your artistic talent as well as your person.”

The Op.101 sonata comes at the start of the composer’s late period, in which his music becomes deeply personal, intimate, and harmonically free. In his Opus 101, Beethoven needs just over 20 minutes to create a concise and compelling musical narrative with a range of emotional expression unlike that of any composer before or since.

The First Hammerklavier Sonata

The Op. 101 marks Beethoven’s first reference to the piano as the “Hammerklavier.” However, it was the next sonata in the Beethoven set, the much larger Op. 106 “Hammerklavier,” that would become known by that moniker.

The Op. 101 was the only one of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas for which he ever attended a public performance.

NADIA BOULANGER (1887-1979): TROIS PIECES FOR CELLO AND PIANO (1914)

Influencer to the Stars

Nadia Boulanger was among the very most influential musicians of her time. Musical luminaries such as Daniel Barenboim, Aaron Copland, Philip Glass, Quincy Jones, and Astor Piazzolla all sought out Boulanger for guidance. Boulanger also enjoyed a long and close relationship with Igor Stravinsky.

Breaking the Glass Ceiling Early

Boulanger was the first woman to conduct some of the foremost orchestras worldwide, including the Hallé, the BBC Symphony, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. While maintaining her primary residence in Paris, Boulanger also taught composition at many of the world’s top music schools, including the Royal Academy of Music, the Juilliard School, the Menuhin School, and the Royal College of Music.

Boulanger had already achieved recognition as a gifted composer before she began to devote herself to conducting and teaching in the 1920s. Her 3 Pieces for Cello & Piano were initially written in 1911 for organ, were transcribed for cello by Boulanger in 1914 and published by Heugel a year later.

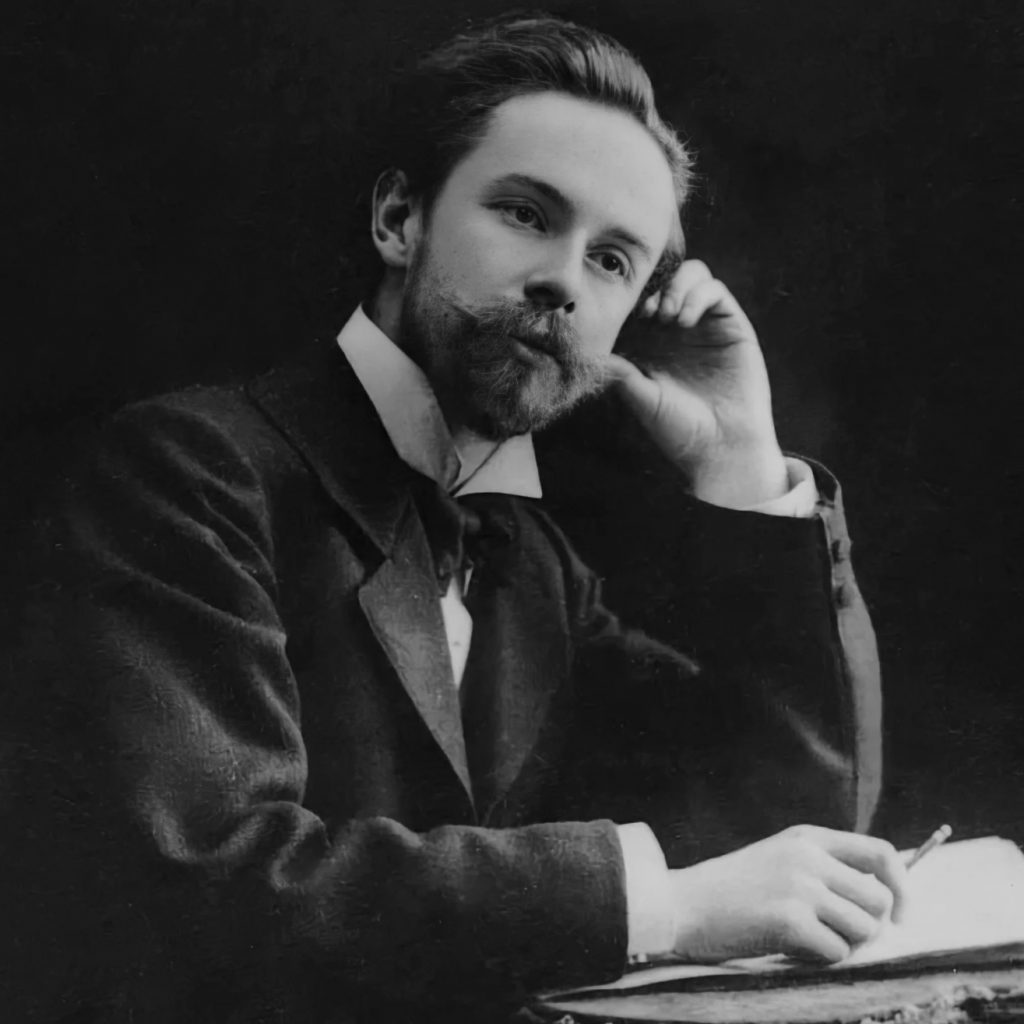

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1872-1915): POÈME, OP. 32, NO. 1 FOR CELLO AND PIANO (1903) (ARRANGED BY GREGOR PIATIGORSKY)

Living Dangerously

Despite Alexander Scriabin’s short life and limited artistic output, his works and theories still inspire passionate debate. Scriabin remains one of the most polarizing figures in music history. Scriabin’s later music and writing reflect a propensity for dangerous musical and sensory experiments, unprecedented theories connecting sound to color, and a fascination with mysticism and ritual. But the composer’s unique voice and signature harmonies are also evident in his early work.

Still a Romantic

Scriabin wrote his Poème No. 1, Op. 32 in 1903, during a productive period for the young composer. In Poème No. 1, we can hear the beginnings of Scriabin’s experiments with a bold new musical language within the romantic conventions of his training. The piece opens with ambiguous harmonies but stops short of the total uprooting of expected harmony that characterizes his later works. The result is an affecting short piece that fits well on many programs.

Scriabin is best known for his piano works. In fact, Poeme No. 1 was composed for solo piano before being adapted for cello and piano by the great Russian cellist, Gregor Piatigorsky.

CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918): SONATA FOR CELLO AND PIANO (1915)

A Return to Chamber Music

In his memoirs, the publisher Jacques Durand related that a performance of the Saint-Saëns Septet at the Concerts Durand in 1914 inspired Debussy to return to chamber music, after a decade-long gap following his highly successful quartet of 1893. Durand encouraged Debussy to proceed with the writing of an intended set of six sonatas for various instruments, in homage to the 18th-century French composers Couperin and Rameau.

Potpourri

Writing to conductor Bernard Molinari, Debussy explained that the set should include “different combinations, with the last sonata combining the previously used instruments.” The plan was thwarted by Debussy’s untimely death on March 25, 1918, but not before three of the six sonatas had been completed and published by Durand, with a dedication to Debussy’s second wife, Emma Bardac.

Debussy completed the Sonata for Cello and Piano in 1915. It was first performed in London on March 4, 1916, and then again in Geneva a few days later. On March 24, 1917, the official premiere in Paris included Joseph Salmon playing cello and Debussy himself on the piano.

A Controversial Pierrot Reference

The cellist Louis Rossoor took up Debussy’s Sonata for Cello and Piano early on. Rossoor connected the work to the popular commedia dell’arte figure, Pierrot, in concert programs: “Pierrot wakes up with a start and shakes off his stupor. He rushes off to sing a serenade to his beloved (the moon) who remains unmoved.” Rossoor claimed that this reference came directly from Debussy, who complained to his publisher that Rossoor had abused his confidence in publishing the description. According to Debussy, the Pierrot reference was easily misunderstood and unnecessary to understand the piece, even if it did relate to it.

The extent of the Pierrot connection in Debussy’s Sonata for Cello and Piano thus remains a mystery. Still, we can take Debussy for his word that the piece can be understood and enjoyed without further explanation.

Still “Modern” Music

Debussy’s Sonata for Cello and Piano remains “modern” sounding to this day. Within the three movements of this 12-minute piece, Debussy’s unsurpassed ability to evoke novel perspectives through new harmonic innovations is on full display. The Sonata for Cello and Piano is fully representative of Debussy’s late style, and as such, provides a perfect bookend for the early Reverie with which this program begins.