Aaron Copland: Unlikely Folk Hero

Aaron Copland (1900 – 1990) was an unlikely folk hero. As a composer, he gave American symphonic music a lasting voice, but as a person remained so curiously reserved that even longtime admirers could wonder if they ever knew him. In contrast to his great friend Leonard Bernstein, who was an irrepressible extrovert in all phases of his life, Copland was a private man of many artistic faces, some mysterious and having little resemblance to one another.

Hard to Know

Our view of Copland is inevitably dominated by the famous ballet suites – Appalachian Spring, Rodeo, and Billy the Kid – that continue to have widespread performances in concert halls but are heard mostly as big payoff moments plucked from larger scores, without the context of peaks, valleys, and narrative. We should know Copland better. His life is certainly well documented, whether in Howard Pollack’s excellent biography Aaron Copland: The Life and Work of an Uncommon Man (University of Illinois Press) or in the composer’s own words in Copland 1900 Through 1942 by Copland and Vivian Perlis (St. Martin’s Marek New York). Unlike Bernstein, Copland was anything but confessional, personally or musically. One thing is not in doubt: he was an exemplary musical citizen.

A Friend and Supporter

Having been the star student in Nadia Boulanger’s famous 1920s Paris salon, Copland subsequently sought to integrate jazz into his concert works. He used his fame to organize concert series, bought rounds of beer for his less-flush colleagues, and championed composers who were vastly different from himself, such as Alban Berg. Copland’s opera The Tender Land was written not for a big Metropolitan Opera production but rather to give American singers something they could feel was their own. His politics leaned toward socialism – how else could he write Fanfare for the Common Man? – but he was quiet about it. When younger, he lived a frugal, semi-nomadic life, living quietly in studios around New York and often spending time on retreats in Mexico. He looked like a librarian. His one documented loss of temper occurred one day at the movies with his friend Bernstein, who was talking back to the screen, pleading with Bette Davis not to make a tragic mistake. Copland fumed back to Bernstein: “Would you please shut up?” (Notice that he said “please.”)

No Time for Regrets…

“He’s charming; he’s radiant; he smiles when admirers come up and ask for his autograph. This external life seemed, for a time, to take the place of everything…” said Minna Lederman Daniel (1896-1995), the longtime editor who worked with Copland on the magazine Modern Music. “He still likes everything about him to be merry; he still has no use for sad stories and no time to waste on regrets or mistakes. He remains assured and confident.” This quote from the Perlis book suggests why Copland’s music, even the most heroic, is absent of tragic undercurrents.

The Greatest Musical Citizen Ever?

Copland’s trail-blazing conversion to Americana was his ultimate service to his fellow composers and to the overall wartime and post-war zeitgeist. He delivered something sophisticated and spacious but with distinctively spare chords that didn’t sound like any other country’s music. He also gave other composers a manner they could use in their own way, fashioning a doorway that felt American and then opening it for others to follow. But as much as Copland seemed to capture America’s waving fields of grain, Copland’s ability to define the American experience through music isn’t easily explained. Curiously, the starting point of it all was Mexico. Copland loved his time there, and after visiting some local dance halls, he came out with the 1936 El Salon Mexico, which showed how the folk culture of America could indeed be enshrined in the concert hall. The piece was an immediate hit.

Simple Gifts

Copland approached the opportunities created by his growing fame with his typical sense of deliberation and integrity. A close listen to his 1938 Billy the Kid ballet shows the modernist Copland lurking not far under the surface. What we now call Appalachian Spring (1944) originally had Copland’s un-sexy title, Ballet for Martha. Later in life, when I asked Copland why he chose the Shaker tune Simple Gifts for the crowd-pleasing ending, he said, “It was in the public domain.” Certainly, that response was tongue-in-cheek. Simple Gifts is just too compelling, beguiling, and winning in the context of Appalachian Spring to have found its way there as a business decision. Copland wasn’t inclined towards musical catharsis. But Simple Gifts did that for him and for posterity in Appalachian Spring.

Embracing Serialism

Copland had experimented with modernism with limited success in works such as his 1950 Piano Quartet. Thus, when his embrace of serialism with Connotations (1962) and Inscape (1967) was perceived as an unconvincing betrayal of his previous self, he was, in fact, simply continuing something already present in his oeuvre, but little known by the public. Nobody, perhaps not even Copland himself, realized that these works would mark the end of his composing career. Although no longer writing, Copland continued to be a public figure, collecting awards and conducting his works in concert until he was overtaken by dementia in the early 1980s.

Uniquely Different

During Copland’s last 20 years of supposed compositional silence, small, previously unpublished piano works of his appeared here and there, some discovered when Copland’s associates, such as composer Philip Ramey examined his files. Initially, one must ask why these short works composed between 1925 and 1947 sound so different from everything else he wrote. Maybe they were more personal than usual. Some of the pieces date from the thick of the Great Depression, when Copland was so overwhelmed by European composers fleeing Nazi Germany that he felt he was composing “in a vacuum.” We can also note that America at the time lacked a solid tradition of new solo piano music exemplified in Europe by Chopin, Liszt, and Brahms. Copland might have thought about filling that void, but what template was there to work from?

The Missing Link

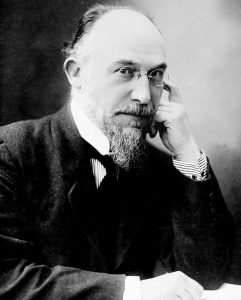

If there’s a missing piece in this puzzle, it’s Erik Satie. Boulanger’s many students were exposed to Satie while in Paris. Satie was also the godfather of Les Six, a fashionable collective of like-minded composers, including Francis Poulenc and Darius Milhaud. Satie was deeply eccentric, and practical-minded Americans were not likely to follow his lead in his more dadaist works such as the ballet Parade. But Satie’s simple, direct piano music, such as Gymnopédie 3, were a major influence on Virgil Thomson and may have had an impact, though a lesser one, on Copland as well. Copland talked about composing with “imposed simplicity,” for which Satie couldn’t have been a better model. Copland’s description of Satie might also describe his own piano miniatures. “[Satie] had a program for French music: It had to be anti-German, anti-grandiose, anti-impressionist, and even anti-impressive.” That last part – “anti-impressive” – is maybe the most radical of all. That quality in Copland’s piano pieces is one reason why they’re hard to fathom – and document.

Three Piano Miniatures

Some of Aaron Copland’s least-known faces can be found in three piano miniatures that did not surface until decades after they were written. Sunday Afternoon Music, Midsummer Nocturne, and Sentimental Melody represent abandoned and forgotten projects and roads not taken, as well as a little-known stream of American solo piano music that was maybe meant to be private.

Sunday Afternoon Music is listed in some sources as having been written in 1925, 1935 in others. Its Satie-style seven-note melody is hypnotically repeated, with a bass line sometimes supporting the treble but not a great source of harmonic or emotional stability. Midsummer Nocturne, which is consistently dated 1947, is also based on an asymmetrically-fashioned seven-note melody, though its form suggests a song without words.

In the mid-1930s, Copland wrote Sunday Afternoon Music for a multi-composer effort by publisher Carl Fischer. Midsummer Nocturne was meant for a later, possibly three-volume series of piano works for young people, perhaps an American version of Bartok’s Mikrokosmos. In any case, it was forgotten until Copland’s fellow composer Philip Ramey found the piece in Copland’s files. It was revised and published in 1977.

Most haunting of all is Sentimental Melody. There are no seven-note melodies, but many elements give a sense of constantly shifting sands, such as bass writing that only supports the bluesy treble intermittently. Metrically speaking, it’s full of triplets, but written over two notes rather than the usual three, as if to acknowledge a third note that should be there but isn’t. Written in 1926 or 1929 (depending on the source), it’s the hardest piece to place in Copland’s piano output. Though subtitled Blues No. 1, Slow Dance, the piece is not part of the set of Four Blues in the Boosey & Hawkes “Copland Piano Collection.” The Aaron Copland website mentions various repurposing plans that may or may not have happened at some point.

What is sentimental about Sentimental Melody? In these three pieces – all miles away from Copland’s majestic Symphony No. 3 – listeners are challenged to ponder the significance of the respective titles. Are they apt? Were they smoke screens for something more private, as titles often were for Satie? If Sentimental Melody, for one, is anything but what it says it is, then what is it? Like Copland himself, the unlikely American folk hero, this will remain ever familiar and yet, in many ways, unknown.