Beethoven and the Cello: A Complicated Relationship

Ludwig van Beethoven held anything-but-typical views on composing for the cello, so much that what was revolutionary in the 18th century would continue to be unlike anything in the 21st century.

Cello was mainly a supporting instrument in Beethoven’s time, even if it was important enough for J.S. Bach to write his six Cello Suites (ca. 1723), long considered exercises for building cello technique. Cello concertos by CPE Bach, Franz Josef Haydn, and especially Luigi Boccherini were all out and around in the 18th century. However, Dvorak and Elgar’s soulful, lyrical concertos that would define the instrument’s personality came long after Beethoven’s death in 1827.

If one word could encompass Beethoven’s distinctive thinking with the cello, it’s rhetoric. Beethoven often made the cello sing but more frequently made it exclaim, not just in his volatile early sonatas of 1796 but in the arresting fugue — unlike anything in the cello literature before or since — that concluded the last sonata, Op. 102 No. 2, written in 1815.

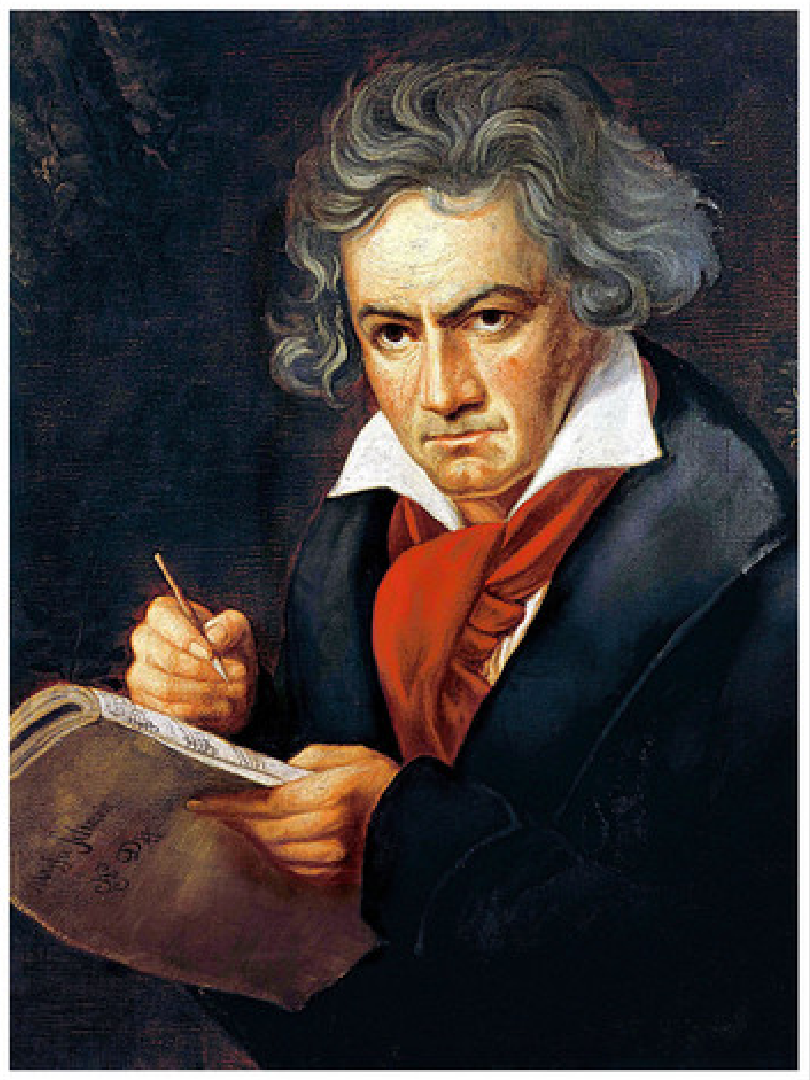

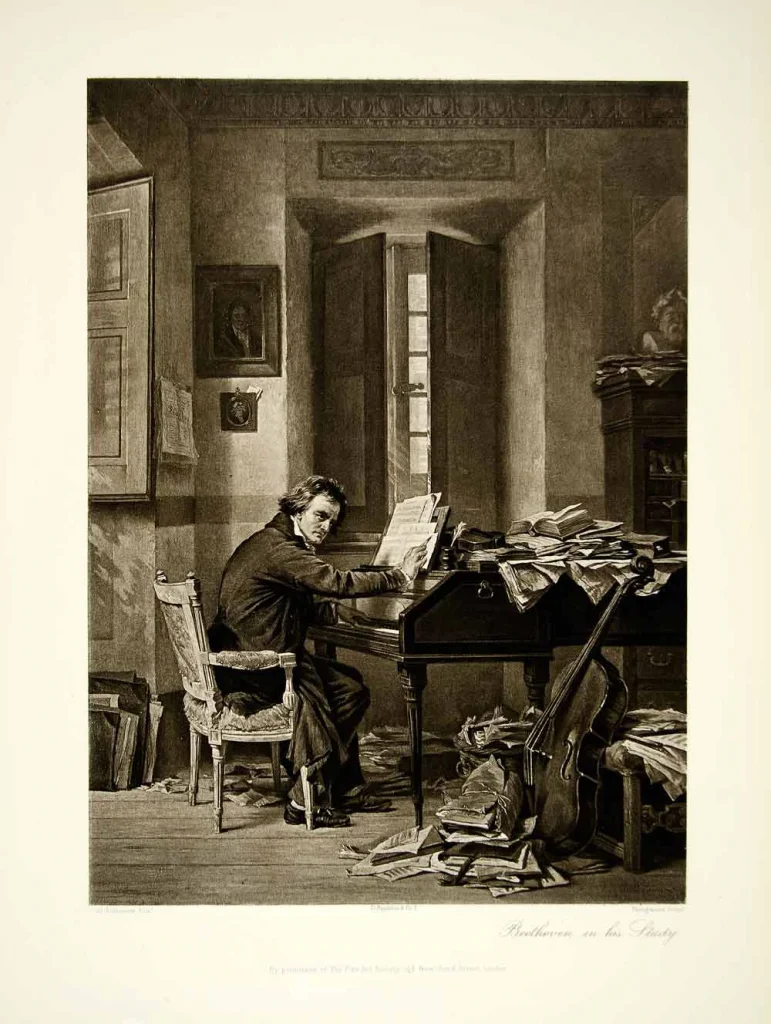

The milder manner of the works that came before him, one must remember, came from a world where the state of the instrument didn’t allow the range of expression that Beethoven sought for each instrument for which he wrote. Also, the more disposable culture of the 18th century meant that recreational music, however cultivated, was only expected to be heard once or twice. In contrast, Beethoven’s music demands repeated contemplation – over a lifetime. His manuscripts are battlegrounds of ideas; he was hardly one to let his hard-won creative breakthroughs drift into the ether. He was a composer who spoke as much to the future as he spoke, quite emphatically, to his own time.

Accidental Symmetry

Such qualities are very much apparent in the cello sonatas. Beethoven’s lyrical cello soliloquies are more like opera recitatives than arias. Beethoven truly appreciated the cello’s ability to dig into a rhythm with an emphasis beyond the powers of the violin. And while Beethoven’s violin sonatas mostly come from his early period, the composer returned to cello sonatas in all three of his creative periods, so much that his cello output seems to have accidental symmetry.

Of the five sonatas, two are from his early period, Two of the sonatas are from his late period. The pairs are like companion pieces, with two sonatas each written in the same respective year. Op. 5 No. 1 in F major, and Op. 5 No. 2 in G minor, were written in 1796, while Op. 102 No. 1 in C major, and Op. 102 No. 2 in D major, were written in 1815.

In the middle, Cello Sonata No. 3 in A major Op. 69, stands alone, written 1807-08 during that middle-period crossroads when Beethoven’s fully-developed genius was bearing fruit with crystalline ideas full of popular appeal. It’s also the only one of Beethoven’s cello sonatas with three designated movements. All of the others have two exceptionally well-packed movements.

Sophisticated Conversations

The body of works together earns Beethoven credit for inventing the modern cello sonata. Though Antonio Vivaldi wrote cello sonatas in the generations before Beethoven, such pieces were short of breath and not especially ambitious. Was Beethoven an intentional agent of change? My feeling is that these sonatas were a natural expression of his personality. Whatever instruments he was using, Beethoven was one to harness them to the maximum, and then some. He took an active role in the evolution of the piano (working with instrument makers), and his cello writing is thought to reflect the influence of the most modern bows. Also, however structurally cogent, the actual pieces became the kind of sophisticated conversations among instruments that the socially-challenged Beethoven was perhaps unable to have in everyday words.

A product of a rough alcoholic household, the composer seemed not to know the meaning of charm, even as he began moving in the kind of aristocratic circles where his cello sonatas were requested. One observer described him as “a bad-tempered little donkey” – one of the many details gleaned from Beethoven’s Cello: Five Revolutionary Sonatas and Their World, the excellent 2017 book by Marc D. Moskovitz and R. Larry Todd. Nonetheless, his two sonatas Op. 5, were written and premiered while he was in the Berlin court of King of Prussia Friedrich Wilhelm II. Friedrich Wilhelm was himself a cellist but can’t have heard anything like Beethoven, especially how the cello and piano tickle each other with great musical intricacy in his sonatas.

The Moskovitz/Todd book, which is said to be the only one on Beethoven’s cello sonatas in the English language, is an excellent resource for analyzing the minute key relationships that were the building blocks of the sonatas. But for less-scholarly listeners, the main point of the Op.5 sonatas, each of which opens the two programs at Guarneri Hall, is how a great musical mind remade the musical world so radically at a young age. One small example is the dotted rhythms employed in Op. 5 No. 1. The Moskovitz/Todd book makes much of the regal origins of that French/baroque compositional technique, and that’s worth noting. But for me, Beethoven takes that gesture to a universal place that can make a different emotional impression in every performance.

Initially, one can wonder if the Op. 5 sonatas are mistakenly incomplete. Each one has only two movements, the first ones being long and eventful, but are best heard as several movements in one. The exposition-development-recapitulation format typical of this era is augmented at the beginning with a slow introduction and the end by a coda, which the Moskovitz/Todd book explains eloquently. The introductions are particularly fascinating: The Op. 5 No. 2 introduction is at least five minutes long (a significant bit of real estate in this world). It shows Beethoven going where inspiration leads him, suggesting the kind of improvisational mind for which Beethoven was famous in his own time as a performer.

The expansive freedom of expression that Beethoven enjoyed is also apparent in the way the gothic atmosphere of the Op. 5 No. 2 introduction doesn’t necessarily carry over into the rest of the movement. There’s a brief decompression period at the start of the first-movement exposition, almost like wiping away the cobwebs of a bad dream before the movement finds its legs. The home key is G minor, but that doesn’t mean there’s no sun amid the clouds. Long before Gustav Mahler tried to encompass the world in his gargantuan symphonies, Beethoven was creating terrarium-like worlds in these cello sonatas that were, in their way, just as eventful and diverse, with more than their share of micro-climates.

Miracles of Invention

Cello Sonata No. 3 Op. 69 is the most beloved of the Beethoven cello sonatas and with good reason. The Op. 69 sonata was conceived around the time of Symphony No. 5 and Violin Concerto, and was completed in 1808. It is one of those miracles of invention in Beethoven’s chamber music output, along with the String Quartet No. 10 in E-flat major Op. 74 (“Harp”) and Piano Trio in B-flat major Op. 97 (“Archduke”). The musical ideas of the Op. 69 sonata flow with a blessed sense of inevitability that is utterly incongruous with the seemingly ruthless revisions found in the sonata’s manuscript pages.

Cello and piano not only have equality in Op. 69, but independence. Certainly, they pick up on each other’s ideas, and accompany each other when needed. In their best moments, they each go their separate but related ways, but with perfect though alternative simultaneous logic that ultimately lands them in the same place. It’s often observed that though Beethoven wrote slow music in his cello sonatas, that music rarely feels slow because there’s so little repose and so much going on. But he came close to writing a slow movement in the third movement of Op. 69 in the introduction to the third and final movement, as “Adagio cantabile” gives way to “Allegro vivace.”

Arriving at the Op. 102 sonatas, one feels that Beethoven has been through a lot both musically and personally in the intervening seven years. Amid personal turmoil, the composer was composing rather less music but more artistically ambitiously and in ways that inhabit the private world of his encroaching deafness. Immediately in Op. 102 No. 1, one notices that melodic appeal has receded in importance – better to reveal the advanced mechanism of the piece. Beethoven casually pulls off a major innovation when the first movement’s main theme returns in the slow introduction to the third moment. Such things just weren’t done in 1815.

While Op. 102 No. 1 sits on the cusp of old and new Beethoven, Op. 102 No. 2 is truly a leap into the composer’s future as each succeeding movement plays by more unprecedented rules. The composer’s interest in melodic content seems even more perfunctory – but with a development section full of leaps of imagination that would be breathtaking if breaths were possible amid music so compressed.

Ideas Both Humble and Exalted

Ideas both humble and exalted often live cheek by jowl in Beethoven, the most obvious example being a Turkish march stuck in the middle of the Symphony No. 9 finale. Still, one can’t help being bewildered when the Orpheus-like lament of the Op. 102 No. 2 “Adagio” movement evolves to become something comfortably bourgeois before returning to the incipient darkness of the underworld. The final movement is an ingenious fugal construction with a certain amount of brinksmanship: the contrapuntal thickets repeatedly threaten to unravel with a number of musical strands going in many directions. The Finale of Op. 102 No. 2 is a fitting closer to the five cello sonatas. It is a movement that takes its place alongside other late-Beethoven works providing a glimpse of the language to come in a far bigger, even-more-exalted Op. 133 Grosse Fugue a decade later. Beethoven’s journey through yet another creative light-year began at the end of his last cello sonata