Of Dumkas and Furiants: Dvořák’s Music of Melancholy and Joy

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) wrote some of the most likable music in the classical repertoire. From his nine symphonies and operas to his copious amount of piano music, sacred choral works and significant body of chamber works, Dvořák’s genius overflowed with memorable melodies. And even when there’s a melancholy strain in his music, as there often is, one senses Dvořák’s optimism and ultimate belief in the goodness of the universe.

Of course, what makes Dvořák’s music so distinctive is how rooted it is in Bohemian soil. Slavic melodies and rhythms give his music its delightfully unique flavor. A fine example of the nationalistic element in Dvořák’s music is his Piano Quintet No. 2 in A major, Op. 81, composed in 1887. It is the perfect work to introduce chamber music to anyone who thinks they don’t like chamber music. Its melodiousness, warmth and approachability are irresistible. It’s also a beautiful example of Dvořák’s use of Slavic folk music. Although the entire quintet has the distinctive Dvořák Bohemian sound, it’s in the second and third movements where the Slavic influence is most overt.

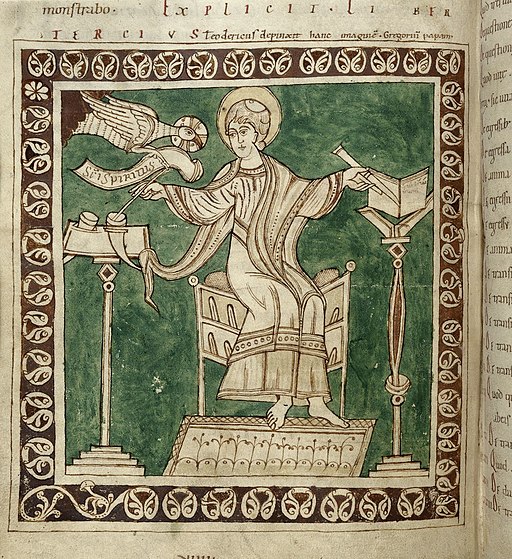

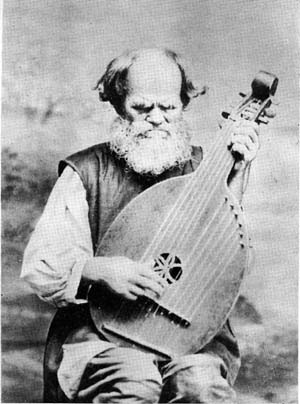

The second movement is a dumka, a musical form derived from dumy, epic poems sung by wandering Cossack bards in Ukraine who accompanied themselves on the kobza, a type of lute. Ostap Veresai (1803-1890) was a blind minstrel, or kobzar, who helped revive and popularize dumy with Russian and Ukrainian audiences. The Ukrainian composer ethnomusicologist Mykola Lysenko published Veresai’s music, and soon composers like Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, and Balakirev were writing their own dumky. The dumky is noted for its bittersweet, melancholic feeling. Listen to the dumka movement of Dvořák’s Piano Quintet No. 2, and you can almost hear the lamentations of a Ukrainian bard in its heart-rending melody.

The third movement of the quintet is a furiant. Composers often followed their dumkas with furiants. The furiant is a fast and furious men’s dance from Bohemia. Its syncopated combination of 2/4 and 3/4 under a 3/4 signature gives the furiant a dash and swagger one would associate with a brash young swain. Dvořák used the furiant in several of his compositions, including the Slavonic Dances and the brilliant scherzo movement of his Symphony No. 6. Smetana also uses it in The Bartered Bride. Even the German composer Brahms used the furiant in the second movement of his String Sextet No. 2. The rapid furiant movement of Dvořák’s Piano Quintet No. 2 is a frisky, good-natured jaunt that perfectly sets up the bright and happy final movement.

A “Simple” Composer of Genius

Dvořák referred to himself as “a simple Czech musician.” This might seem like false modesty, but there is some truth in Dvořák’s humble self-description. There is a simple directness to his music that in no way minimizes its greatness. The gorgeous melodies, heartbreaking harmonies, and always hopeful mood that flows effortlessly through Dvořák’s music can belie its complex genius.

In 1878, the music critic Louis Ehlert captured this quality perfectly when he reviewed the first performance of Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances, Op. 46. Ehlert wrote that “a heavenly naturalness flows through this music.” That naturalness would continue to flow through all of Dvořák’s brilliant compositions. Ehlert wrote that the Slavonic Dances would make their way “round the world.” With the help of champions like Johannes Brahms, the violinist Joseph Joachim and the conductor Hans Richter, Dvořák’s music has become known and loved by audiences everywhere.

The Slavonic Dances by Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) might be some of the most underrated classical music ever written. They contain everything we love about classical music: excitement, deep emotions, thrilling orchestration, and, of course, unbridled joy. And Dvořák captured all these facets with absolute brilliance. Dvořák was inspired by Brahms’ Hungarian Dances, but unlike Brahms, who quoted actual Hungarian folk tunes, Dvořák created his own completely original melodies. He was so steeped in the music of his native land that Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances sound as though they are age-old Slavic folk melodies. The Slavonic Dances helped make Dvořák one of the most famous composers of his age and lifted him out of poverty. They also made the world aware of the rich musical heritage of Bohemia. But even though Dvořák would be lionized as one of the greatest composers of his age, he would always be first and foremost “a simple Czech musician.”

From Poverty to Fame

Few composers have been as rooted in the soil of their native land as Dvořák. He was born in the village of Nelahozeves in the heart of Bohemia. His father was an innkeeper and a butcher, as well as a zither player. Dvořák began his musical career in the village band and played the organ at the local church. His first composition, the Forget-Me-Not Polka, written when he was around 14, was a foretaste of how important the Slavic influence would be to Dvořák’s music.

At the age of 16, with the encouragement of his father, Dvořák left for Prague to continue his musical studies. At the insistence of his father, who hoped he would eventually become a church musician, Dvořák studied at the Prague Organ School. He excelled at his studies, and to make extra money, performed with various bands and orchestras. It was while he was playing in the prestigious Bohemian Provisional Theater Orchestra that he first encountered the music of Richard Wagner. Dvořák would admire Wagner’s music for the rest of his life.

While living the life of a struggling musician, Dvořák married Anna Čermáková, with whom he had nine children. Dvořák continued to work low-paying jobs, including that of a church organist, but always found time to compose. His life of obscurity and poverty ended in 1877, when his Moravian Duets and his Piano Concerto won the Austrian Prize Competition. The well-known critic Eduard Hanslick personally informed Dvořák that Hanslick himself and Brahms had been on the jury. Brahms would forever remain a devoted friend and advocate of Dvořák’s music.

Dvořák Brings Bohemia to the World

Dvořák started to receive commissions and soon became an international music celebrity. He was one of the most well-traveled composers of his day. He conducted his own music in Moscow (at the invitation of Tchaikovsky), toured England, which he visited eight times, and was a welcome visitor to Germany. Dvořák also famously spent a considerable amount of time in the United States, where he became the director of the National Conservatory of American Music in New York from 1892 to 1895. While in America, he spent a summer with the Czech community in Spillville, Iowa in 1893, playing the organ and watching trains, a favorite pastime. It was in Spillville that Dvořák wrote his famous “American” Quartet and finished his “New World” Symphony. Wherever he traveled, Bohemia was always in Dvořák’s heart, and no matter the accolades he would receive in other countries, he always longed to return to his fatherland. Dvořák was the perfect composer to musically express the nationalism of the Czech people that blossomed in the 19th century.

The Right Composer at the Right Time

After the Hapsburg Empire secured control of Bohemia in 1620, the Czech people were “Germanized.” The Czech language was systematically eliminated from the state bureaucracy, schools, and literature. The upper classes embraced the German language, and Czech was reduced to the language of the peasants and almost completely eradicated. The Czech National Revival is said to have begun when the first Czech grammar book was published in 1809. From 1834 to 1839, a five-volume Czech-German dictionary was published, and soon the Czech language was flourishing, and the Czech National Revival was in full swing. As the language revived, the rest of Czech culture also started to undergo a renaissance. Music was an important part of the Czech National Revival and Dvořák and Smetana, the composer of Má Vlast (My Fatherland) and The Bartered Bride, were poised to become the greatest exponents of Czech music.

The Sun Always Shines in Dvořák’s Music

Dvořák’s influence has lived on beyond the nationalistic 19th century. His inspiration can be clearly discerned in composers of the generation immediately following him, like Leoš Janáček, Bohuslav Martinů, and his son-in-law Josef Suk. But one surprisingly hears echoes of Dvořák’s Bohemian romanticism in more contemporary composers. Slovak Peter Breiner (b. 1957) has conducted a superb cycle of Janáček recordings for the Naxos label, as well as some outstanding arrangements, including the Naxos Christmas Choral Spectacular. In 2020, Breiner recorded a two-disc set of his own Slovak Dances, Naughty and Nice which owe an obvious debt to Dvořák’s Slavonic Dance.

Vladimír Godár (b. 1956) is not well known outside his native Slovakia but should be. In 2006 ECM released a delightful album of his sacred music filled with Bohemian rhythms and childlike joy. Besides the folk influence, it is joy which really distinguishes Breiner’s and Godar’s music. And perhaps that is Dvořák’s most important legacy to composers of today.

Dvořák once said that “Mozart is sunshine.” The same is true of Dvořák himself. He was a man who went through intense periods of suffering. He endured years of poverty and the deaths of three of his children in infancy, as well as the death at 27 of his eldest daughter, Otile, a gifted pianist and composer. But this lovable man, imbued with a profound spiritual faith, who deeply loved his wife and family and enjoyed watching trains in his spare time, always saw the sun behind the clouds. For Dvořák, the bittersweet sadness of the dumka would always be followed by the dancing joy of a furiant.