Timothy Chooi Recital Program Notes

Amy Beach: Romance

Amy Beach (1867-1944) was one of the most remarkable composers in history. By the age of four, she had taught herself how to read, could sing forty songs and had composed three waltzes for piano. As a child, she was giving recitals of music by European masters, as well as her own compositions. By the time she was a teen, she was concertizing with Boston’s finest orchestras.

All that changed, however, when she married Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach, a renowned surgeon and lecturer at Harvard who was 24 years older than she. As a member of Boston society, Beach set aside her concert career, except for two charity concerts a year. According to her biographer, Fried Block, Beach had to agree to live according to her husband’s status, “that is, function as a society matron and patron of the arts. She agreed never to teach piano, an activity widely associated with women and regarded as providing ‘pin money.’”

Although her public performances, for the most part, came to an end during her marriage, she continued to compose. Some of her most notable works include the Mass in E-flat, a piano concerto, and the Gaelic Symphony, the first symphony written by an American woman.

In 1893, she composed “Romance,” a piece for violin and piano, and dedicated it to Maud Powell, an acclaimed American violinist of the day. Powell gave the piece its first performance. “Romance” lives up to its name with a passionate yet gentle lyricism that sweeps up the listener. After the work had its premiere in Chicago on July 6, 1893, the Chicago Times wrote that the audience “cheered to the echo” and the work had to be repeated.

After her husband died in 1910, Beach spent time in Europe and returned to concertizing. Her works were starting to get attention overseas, with performances of her Gaelic Symphony in Hamburg and Leipzig. When she returned to America in 1914, she continued to give recitals and became very involved in music education, helping young musicians as much as she was able. At the end of her life, she was composer-in-residence for St. Bartholomew’s church in New York City. The history of American music would be much the poorer without Amy Beach.

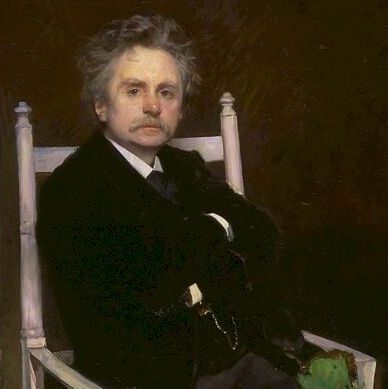

Edvard Grieg: Sonata No. 3 in c minor

Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) wrote the most lovable music. The Peer Gynt Suites, the Holberg Suite and the Piano Concerto are a few of his more popular works. His chamber music is much less well-known, but it has the same sweet lyricism and gorgeous folk melodies that make his larger works so enjoyable.

Grieg wrote three violin sonatas which are beautiful examples of his Norwegian musical nationalism. The third sonata, the most popular of the three, took Grieg the longest to compose. Although the sonata has distinctly Norwegian-sounding melodies and rhythms, Grieg said that this sonata was “the one with the broader horizon.”

The sonata opens forcefully before Grieg’s lyrical second theme makes its appearance. The second movement begins with the piano playing a calm, gentle melody, then the violin enters and soon plays a folk-like dance before the movement evolves into a darker mood. At the beginning of the final movement, a frenzied march is heard, reminiscent of Grieg’s “March of the Trolls.” When the march dissipates, a romantic theme emerges before the march returns, this time joyously concluding the sonata in triumph.

Chen Gang: Sunshine on Tashkurgan

Chinese composer Chen Gang (b. 1935) lived through the tumultuous years of the Cultural Revolution. His most famous work is The Butterfly Lovers violin concerto, composed in 1959, right on the cusp of the chaos that was soon to engulf China.

Gang’s lush, romantic, melodic approach to music has a lot of mass-appeal, which allowed it to survive the Cultural Revolution. Gang continued to write music throughout the tumult, and from 1973 to 1976, he composed nine works with titles like “The Golden Steel-Smelting Furnace,” “The Morning of Mount Miao” and “Sunshine on Tashkurgan.”

Tashkurgan, which means “stone fortress” or “stone tower,” is a northwestern Chinese town on the border with Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan. It was an important stop on the Silk Road. “Sunshine on Tashkurgan” is a showstopper that is based on Tajik folk melodies.

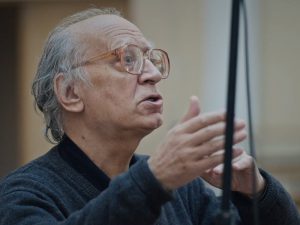

Valentyn Silvestrov: Postlude for Solo Violin No. 2

Valentyn Silvestrov (b. 1937) composes some of the most distinctive music of our day. At times, it’s lush and romantic, at other times austere, perhaps recalling the sacred minimalism of Arvo Pärt. But Silvestrov sounds like no one else.

Silvestrov was born in Kyiv, Ukraine, when it was still part of the Soviet Union. While studying piano at an evening music school, he studied to be an engineer during the day. Following the sad, familiar fate of so many Soviet composers, Silvestrov was pressured to write socialist realist music. After he was forced to apologize for walking out of a composers’ meeting in protest of the Soviet Union’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Silvestrov decided to retire from public life.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Silvestrov reemerged, and his music began to be influenced by Orthodox chant and spirituality. Although in his early years, Silvestrov dabbled with atonality and avant garde techniques, as time went on, he became disillusioned with musical modernism. As he put it, “I do not write new music. My music is a response to and an echo of what already exists.”

Silvestrov wrote a series of pieces called “Postludes,” works which look back, often wistfully, on the history of music. He wrote many works for large forces, but the Postlude for Solo Violin No. 2, composed in 1981, distills the essence of Silvestrov. The piece has an ancient, almost liturgical sound that seems to contemplate the mysteriousness of the universe.

Karol Szymanowski: Nocturne and Tarantella

The music of Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) reflects several diverse influences. While drawing on music of his native Poland, Szymanowski was inspired by various composers and schools of music in different stages of his life. In his early career, he was immersed in the sound world of late Romanticism. One hears echoes of Alexander Scriabin and Richard Strauss in early works such as his Symphony No. 2.

In what could be described as his middle period, Szymanowski was infatuated with impressionism, but he also experimented with atonality. In his late period, Szymanowski started to study the music of the Gorals, an indigenous people of Poland. Its rhythms and vitality can be heard in his Fourth Symphony, as well as the many mazurkas he wrote for piano.

The Nocturne and Tarantella was written early in his career in 1915. Szymanowski supposedly sketched out the entire work after a night of drinking with violinist Patel Kochański. The work was given its premiere by Kochański and pianist Feliks Szyanowski, the composer’s older brother.

At the time he wrote the work, Szymanowski was absorbed in studying Islamic culture, ancient Greek literature and philosophy. The nocturne begins with a sinuous, Middle Eastern-sounding lyrical line, but it quickly starts to sound Spanish, reflecting Szymanowski’s recent travels in the Mediterranean. The tarantella is appropriately frenzied and provides a rousing conclusion to this showpiece for violin.

Timothy Chooi performs at 6:30 p.m. March 28 at Guarneri Hall, 11 E Adams St Ste 350A, Chicago. $10-$40. 847-780-6720: link for tickets.