Mozart, Stravinsky, and Beethoven: Spring Strings Program Notes

Mozart, Stravinsky and Beethoven aren’t names often seen together in the same sentence. Nor do they often share a program of chamber music, as they do in the Lincoln Quartet’s May 16 Concert at Guarneri Hall. The outlier is Stravinsky, whose steady output of ballet scores make him an infrequent presence in chamber music. But what might his sense of theater tell listeners about Mozart and Beethoven?

Operatic Subtext

It’s often said that everything Mozart wrote had operatic subtext. Even if one doesn’t entirely buy into that, the idea might at least open one to hear Mozart with different ears. His String Quartet No. 22 in B-flat major, K.589 opens the Lincoln Quartet’s program at Guarneri Hall on May 16. The piece demonstrates the composer’s graduation from his dazzling six quartets dedicated to Haydn. In 1790 Mozart composed three so-called “Prussian” quartets for the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm II, whose own abilities on the cello account for why the instrument is featured prominently in the music. The theatrically isn’t easy to hear here; Mozart’s K.589 is more compressed than usual. The composer was going for a more continuous flow, with less obvious structural signposts and ideas that aren’t as arresting, charming, and sparkling as in his earlier quartets. Mozart was in transition, but where he was headed was left to speculation – he died the following year.

Beyond the Rite of Spring

Igor Stravinsky was beset with a unique early-career problem: what do you write after the world-changing Rite of Spring? One of several answers over the next few years was his Three Pieces for String Quartet, which is shocking if only in its modesty, especially when flanked by Mozart and Beethoven in the Lincoln Quartet’s May 16 program.

Stravinsky’s foray into the string quartet medium is among his quirkiest works – three pieces that sound, act, and behave as though they don’t belong together. The first piece stubbornly resists thematic development. The third and longest piece sustains itself with innovative collage effects. Certainly, something theatrical is at work here. Stravinsky’s compositional process was about creating the world of the music inside him, constrained by his self-established limitations that would tell him what that world could be. Such considerations dictated the orchestral palette (each different in every work) and melodic source material (folk songs in The Rite of Spring, Tchaikovsky piano pieces for The Fairy’s Kiss). But could Stravinsky be so misguided as to impose his theatricality onto such a tradition-laden medium as the string quartet? Maybe he was right to try.

Shall We Dance?

Stravinsky’s music lends itself to dance with such a unique, innate physicality that even his Violin Concerto has been choreographed. Stravinsky’s first musical memory, at age three, was indeed physical: a folk musician at a fair making sounds with his tongue and armpit. Regarding Three Pieces for String Quartet, Stravinsky scholar Richard Taruskin tried to impose some analytical objectivity in describing the individual string quartet pieces: “Fragmented-ness. Static-ness. Simplification.” Sounds okay, but doesn’t tell us much. When Stravinsky recycled the music as Quatre Etudes, a new set of subtitles were no more revealing: “Danse,” “Excentrique” and “Cantique.” Clearly there can be no consensus about this music’s meaning. Perhaps it has been drastically repurposed from – one guess only here – a ballet?

According to Stravinsky scholar Stephen Walsh, the first two of the pieces come from an unfinished ballet titled David that Stravinsky worked on at the urging of Jean Cocteau, starting in the spring of 1914 after finishing his opera The Nightingale. The project stalled, and Cocteau recycled his ideas into the famous ballet Parade, which became a surrealist manifesto with music by Erik Satie and sets by Pablo Picasso. But the string quartet music that Stravinsky had written – with an added third movement inspired by Orthodox chant – was more than cold comfort.

Three Pieces for String Quartet was first performed by the then-famous Flonzaley Quartet, who were eager for a Stravinsky quartet for their 1914 world tour, suggesting how the composer – whose life then had domestic difficulties and financial challenges – was in demand in any medium. From there, Stravinsky went on to compose one of his most admired pieces, the folk-based ballet Les Noces. If Three Pieces for String Quartet was the laboratory for that great piece, then it’s worth our repeated attention. And if nothing else, the music must be credited for keeping us guessing.

Theatricality is, in fact, a time-honored tradition in chamber music, but one that manifests itself so differently from composer to composer and often so far under the surface that it can escape the attention of even the most attentive listeners.

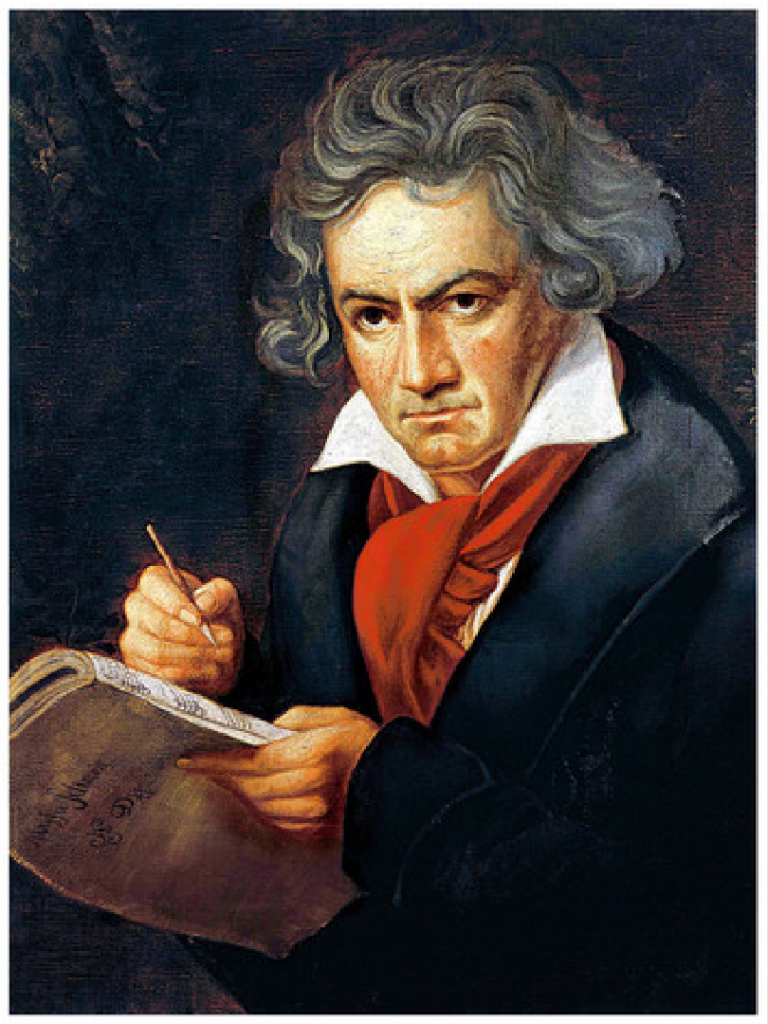

An Unlikely Candidate for the Theater

Beethoven would seem to be the least likely candidate for bringing the theater into the string quartet medium. It’s true that his Symphony No. 2 does have the manic narrative of comic opera, but his ballet Creatures of Prometheus isn’t great, aside from the sections he repurposed for the Symphony No. 3 (“Eroica”). Beethoven’s opera Fidelio contains genuinely great music but is rarely staged convincingly. The composer is represented on this program by the String Quartet No. 9 Op. 59 No. 3, the third of the composer’s imposing, Russian-tinged “Razumovsky” cycle. The piece (nicknamed “Heroique”) is the subject of one of the best-reasoned chapters in Beethoven’s Theatrical Quartets: Opp. 59, 74 and 95 (Cambridge University Press, 282 pages) by New Zealand-based musicologist Nancy November.

“Public address” – more than “public discussion” – is how Beethoven scholar Adolf Bernhard Marx (as quoted by November) characterizes the manner of Op. 59 No. 3. Beethoven wrote the Op. 59 quartets closely on the heels of the 1805 premiere of Fidelio, then called Leonore, and they almost qualify as an extension of the opera. November goes on to discuss the quartet’s concerto-like gestures in the first movement, the second movement’s possible basis in Russian song (‘Ty wospoi, wospoi, mlad Shaworontschek’), the choice of a minuet rather than a scherzo in the third movement, and the complexities of the fugal finale. November uses imagery such as bungee jumping, and more. “Heroic codes of early nineteenth-century stringed instrument performance are again in evidence: in multiple stopped chords, the upper instruments brandish their bows like rapiers, and the cello sounds its sonorous open C once more,” she wrote.

Triumph Over Fugue

Some find a parallel narrative between the second movement of Op. 59 #3 and Fidelio: as in the opera, the song lyrics present an imprisoned man, this one asking a lark to deliver letters to his beloved. November suggests that some of the stabbing figures in Op. 59 No. 3 recall the Fidelio finale, specifically when the heroine Leonore is ordered to dig a grave for a prisoner who might be her husband. The quartet’s finale is typically argumentative Beethoven: “The finale’s plot has arguably more to do with a heroic battle with and triumph over strict fugue; if you will, a staged triumph over traditional quartet discourse,” writes November. Amen.